Poetry 1849

Searching for value

I’m usually a fan of Frederick Melo- but herbal gardens as a necessity of life? I’m a gardener, a pretty good one. I’m an active if not pretty good cook. I’ve tried to tend to herbs and they always fall away. But someone whose life is messy and needs supplemental help is going to grow herbs?

I’d love to see an outcome report from the attendees of the herbal garden classes, as down to earth and healthy as they sound.

Me: It sounds like he (James M Buchanan) wants to believe in self-governance, yet he doesn’t have faith in the distribution of the groupings, hence ‘free riding’, so in the end he supports the cohesion of the state after all.

Grok:

Your observation captures a tension in James M. Buchanan’s work that’s worth unpacking. You’re suggesting that while Buchanan champions self-governance and individual liberty, his concern about free-riding and coordination problems leads him to rely on formal institutional structures, which might seem to endorse the cohesion of the state—potentially contradicting his critique of the organismic view. Let’s explore this interpretation, addressing whether Buchanan’s focus on institutions implies support for state cohesion and how it aligns with his belief in self-governance. I’ll keep the response concise yet thorough, tying it to your previous questions about the organismic concept and group cooperation.

Buchanan’s Commitment to Self-Governance

Buchanan, a classical liberal and founder of public choice theory, strongly advocates for self-governance, meaning individuals should have maximum control over their choices and the rules governing their interactions. His rejection of the organismic concept—where collectives like “the state” or “society” are treated as unified entities with their own goals—stems from his belief that only individuals have preferences and agency. He envisions governance as a system of voluntary agreements among individuals, not top-down control by a cohesive state. Key points:

• In The Calculus of Consent (1962, with Gordon Tullock), Buchanan proposes that political systems should emerge from unanimous or near-unanimous consent at the constitutional level, where individuals agree on rules for collective decision-making. This reflects self-governance, as the state’s authority derives from individual agreement, not an inherent collective will.

• His concept of “politics as exchange” sees government as a mechanism for individuals to cooperate for mutual benefit (e.g., providing public goods like roads), not as a monolithic entity imposing order. This contrasts with organismic views that assume the state naturally serves a unified “public interest.”

The Free-Rider Problem and Institutional Needs

Your point about Buchanan’s lack of faith in the “distribution of the groupings” (i.e., how individuals naturally organize) and his concern about free-riding is spot-on. Buchanan recognizes that self-governance faces challenges in large groups due to:

• Free-Riding: Individuals may benefit from collective goods (e.g., clean air, defense) without contributing, undermining cooperation. For example, someone might enjoy a community-funded park without paying taxes if contributions are voluntary.

• Coordination Problems: Diverse preferences and large group sizes make spontaneous cooperation difficult without agreed-upon rules. Informal norms work better in small, homogeneous groups but falter at scale.

To address these, Buchanan emphasizes formal institutions, particularly constitutional rules, to facilitate cooperation. In The Limits of Liberty (1975), he argues that a social contract—a set of rules individuals consent to—prevents free-riding and ensures fair contributions to collective goods. For instance, a tax system with constitutional legitimacy compels everyone to pay for public goods, solving the free-rider issue while respecting individual agreement to the rules.

Does this mean Buchanan lacks faith in self-governance? Not quite. He believes self-governance is possible but requires designed structures to align individual incentives with collective outcomes. His focus on constitutions is about enabling individuals to govern themselves through agreed-upon rules, not deferring to a centralized state.

Does Buchanan Support State Cohesion?

Your suggestion that Buchanan’s reliance on institutions implies support for the “cohesion of the state” is a nuanced critique. Let’s break it down:

• Not State Cohesion in the Organismic Sense: Buchanan explicitly rejects the idea of the state as a cohesive, sentient entity with its own goals (the organismic view). He sees the state as a collection of individuals—politicians, voters, bureaucrats—each pursuing their own interests. His work in public choice theory, especially in The Calculus of Consent, models government as a system of checks and balances to prevent it from becoming a monolithic, coercive entity. For example, he warns against a “predatory state” that exploits citizens under the guise of public interest.

• Institutions as Tools, Not State Worship: Buchanan’s support for formal governance is about creating minimal, consensual frameworks to enable cooperation, not endorsing a strong, centralized state. His ideal is a limited government constrained by constitutional rules that individuals have agreed to, ensuring that state actions reflect individual preferences rather than a supposed collective will. For instance, his admiration for Knut Wicksell’s principle of “just taxation” requires taxes to be tied to benefits and approved by near-unanimous consent, minimizing state overreach.

• Tension in Practice: You’re right that Buchanan’s reliance on formal institutions could, in practice, lead to a state with some degree of cohesion, as enforcing rules (e.g., tax collection) requires authority. Critics of Buchanan argue that his constitutional framework assumes a level of rational agreement that’s hard to achieve, and the resulting institutions might take on a life of their own, resembling the cohesive state he critiques. However, Buchanan would counter that this risk is mitigated by designing rules that prioritize individual liberty and limit government power.

Reconciling Self-Governance and Institutional Reliance

Buchanan’s position is that self-governance is not spontaneous but requires deliberate institutional design to succeed at scale. He doesn’t distrust individuals’ ability to cooperate but recognizes practical barriers like free-riding and coordination costs. His solution is a two-level governance framework:

1. Constitutional Level: Individuals agree on rules (e.g., voting systems, tax policies) to structure cooperation. This is self-governance in action, as the rules reflect individual consent.

2. Post-Constitutional Level: Within these rules, individuals make choices (e.g., voting, paying taxes) that produce collective outcomes. Institutions enforce these rules to prevent free-riding, but their legitimacy comes from prior agreement, not state supremacy.

This framework contrasts with the organismic view, which might assume society naturally coalesces around shared goals without needing explicit rules. Buchanan’s skepticism of such assumptions drives his focus on institutions, but he remains committed to individual liberty and minimal state intervention.

Addressing Your Critique

You’re correct that Buchanan’s concern about free-riding and group coordination could seem to undermine his faith in pure self-governance, pushing him toward formal institutions that resemble state cohesion. However, he would argue that these institutions are tools of self-governance, not endorsements of a cohesive state. The state’s role is to enforce rules individuals have chosen, not to act as an independent entity. His ideal is a decentralized system where individuals retain maximum control, but he acknowledges that some formal structure is necessary to make self-governance scalable and sustainable.

Conclusion

Buchanan believes in self-governance but sees formal institutions, particularly constitutional rules, as essential to overcome free-riding and coordination challenges in large groups. This doesn’t mean he supports state cohesion in the organismic sense; rather, he advocates for a limited, consensual state that enforces individual-agreed rules to enable cooperation. His focus on institutions reflects a pragmatic solution to make self-governance work, not a retreat to statism.

This Slovenian series is quite good. And best of all, it’s very local. I didn’t even have a good grasp of where this country, with a population of just over 2 million people, was situated. The star, Sebastian Cavazza, plays the moody, ever-searching lead detective of a band of four. His co-workers are a bit quirky and a lot loyal. A new girl joins to stir in some romantic interest.

The story holds, but what makes the whole thing interesting is the glimpse into a new country with all its subtleties and unique characteristics. Even the lead-in music feels Slovenian.

I was just starting to remind myself how tiresome the war scenes are in nineteenth-century literature. Dragoons and flanks, musketeers and battery, Cossacks and campaigns- all so tiring. But then, Tolstoy, that timeless genius, throws these wise words across the page in War and Peace.

Prince Andrey listened carefully to Prince Bagration’s colloquies with the commanding offi-cers, and to the orders he gave them, and noticed, to his astonishment, that no orders were really given by him at all, but that Prince Bagration confined himself to trying to appear as though everything that was being done of necessity, by chance, or at the will of individual officers, was all done, it not by his order, at least in accordance with his intentions. Prince Andrey observed, however, that, thanks to the tact shown by Prince Bagration, notwithstanding that what was done was due to chance, and not dependent on the commander’s will, his presence was of the greatest value.

Sometimes you can see two structures melding in real time. On the one hand the underlings, those closest yo the knowledge, are given the right to choose; on the other hand a charade of power preserves the status of those in charge.

Sometimes, it’s best if public life is not too exacting.

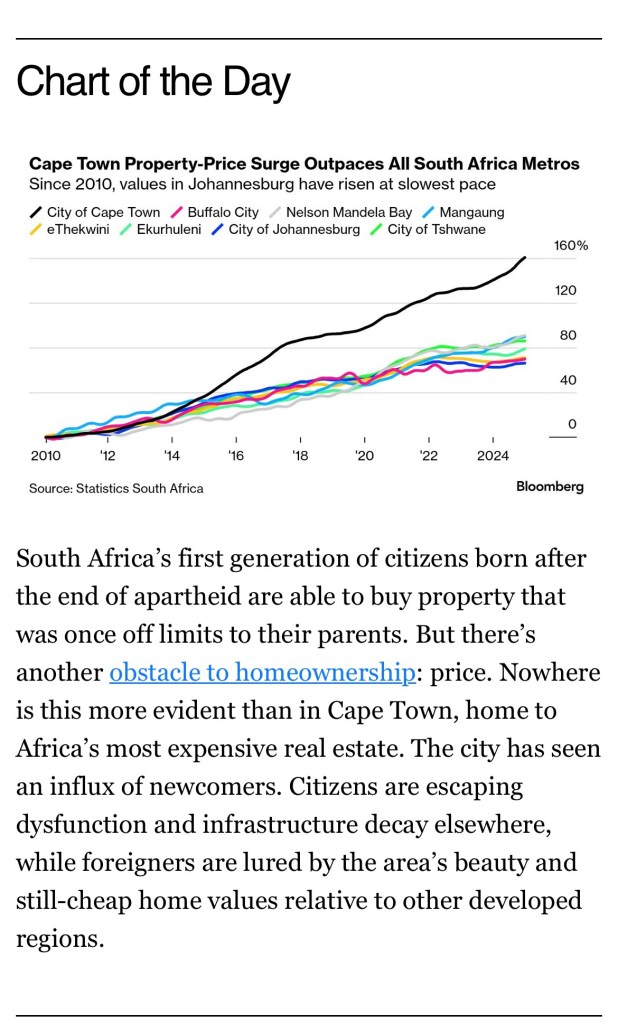

This is from Bloomberg’s news letter a few days ago:

This example comes from South Africa, but the pattern is familiar in city neighborhoods across the United States. A single area becomes highly sought after—often because of a natural amenity like a lake, a hilltop view, or tree-lined streets. As people concentrate their attention and investment there, surrounding neighborhoods are overlooked. That neglect can manifest in subtle forms—like disrepair or increased petty crime—which only reinforces the appeal of the original “best” area.

At first, residents welcome the rising property values. But over time, that early advantage turns into a burden. Friends and family are priced out. Local businesses close as commercial rents climb, replaced by boutique shops that cater to outsiders. What began as a benefit morphs into a form of isolation.

A regional perspective offers a solution. If planners and policymakers ensure that all neighborhoods remain livable and desirable—not just one or two—the pressure on any single area can be eased. Without that balance, scarcity drives runaway prices, and the community as a whole suffers.

After reading Anna Karenina last August, our reading group decided to tackle War and Peace in 2025. It’s a behemoth. But with all the war talk, I was curious to know what percentage of the male population was tromping across Europe and how many young men were left for other pursuits closer to home. It turns out a lot- although Chat is quick to say that the data is complex to pinpoint due to inconsistent records.

Summary

• France: ~50–60% of males aged 18–55 served, driven by universal conscription and mass mobilization (2–2.4 million from 3.6–4 million).

• Russia: ~20–30% served, with serf-based levies mobilizing 1–1.5 million from 3.5–5 million, supplemented by militias in 1812.

• Austria: ~40–60% served, with 1–1.5 million mobilized from 2–2.6 million, using selective conscription.

• Prussia: ~40–65% served, with 500,000–800,000 mobilized from 1–1.25 million, increasing after 1813 reforms.

• Britain: ~25–40% served, with 400,000–500,000 mobilized from 1.2–1.5 million, relying on volunteers and naval press-ganging.

In the Context of War and Peace

The novel reflects these varying conscription rates through its portrayal of Russian serf-soldiers and officers like Andrei and Nikolai, contrasted with the French Grande Armée’s mass-conscripted forces. Russia’s lower percentage reflects its selective serf levies, while France’s high rate underscores the levée en masse’s impact, as seen in the exhausted French troops during the 1812 retreat. The differences in mobilization rates highlight the social and military dynamics Tolstoy explores, with Russia’s feudal system and France’s revolutionary conscription shaping their respective armies.

Note: These percentages are estimates based on historical data and demographic assumptions, as precise age-specific military participation rates are not fully documented. Variations across campaigns and years (e.g., 1812–1814 being the deadliest) affect the figures.

Conscription is a type of forced labor. A citizen’s time is donated to the public good in exchange for some compensation (or at least room and board for the serfs). One can see why, in two hundred years, boots-on-the-ground warfare is unpopular. Too many human hours could be devoted to other public goods or to earning a wage in the commercial market. The opportunities to leverage capital even further should the young men choose to invest in education or learn a trade.

War also produces wounded. This can also shift the stage-of-life abilities of a young, able-bodied male. The labor costs of war are too dear.

I flew into Missoula today and the Montana Airport is wrapping up a major multi-phase expansion that reshapes regional travel and brings broader economic shifts in its wake. Here are some of the details:

Missoula’s airport expansion is more than a construction project — it’s a gateway to growth. With smart federal funding and local vision, the region is positioning itself for a more connected future. But keeping Missoula livable as it grows will take coordination on housing, transportation, and community needs. How would one go about making some projections? Estimates of impacts and time frames could be interesting to local public leaders.

This is an excerpt from my working paper, which examines how contemporary economic realities challenge conventional price formation models. Traditional price theory, rooted in neoclassical equilibrium models, struggles to explain modern markets characterized by digital platforms, behavioral anomalies, and network effects. Rather than viewing prices solely as equilibrium outcomes, this section explores price as an information system and coordination mechanism shaped by institutional contexts and evolutionary market processes, proposing alternative approaches that better capture the dynamic nature of pricing in today’s economy.

B. Comparative Analysis: Evaluating Theoretical Frameworks

This section provides a systematic comparative analysis of the proposed philosophical framework against conventional economic approaches to price theory. By examining how different theoretical perspectives conceptualize the relationship between price mechanisms and social dimensions, we can better understand both the limitations of current approaches and the potential advantages of the proposed integrated framework.

Conventional Economic Frameworks: The Separation Paradigm

Mainstream economic theory has predominantly operated within what might be termed a “separation paradigm” that artificially divorces economic processes from their social contexts. This approach has taken several forms, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings but sharing a common tendency to externalize social dimensions from core economic processes.

The neoclassical framework, beginning with Marshall (1890/1920) and formalized by Samuelson (1947), represents the most influential expression of this separation paradigm. This approach treats social costs and benefits as “externalities”—phenomena that exist outside the market mechanism and require correction through policy intervention. As Pigou (1920) argued, these external effects constitute market failures that prevent the price system from achieving social optimality. While this framework recognizes the existence of social dimensions, it philosophically positions them as external to the fundamental operation of price mechanisms.

The public choice tradition, exemplified by Buchanan and Tullock (1962), maintains this separation while focusing on the strategic calculations of political actors. As Tullock (1965) argues in “The Politics of Bureaucracy,” individuals navigate institutional structures to advance their interests, with social dimensions treated as constraints within a fundamentally individualistic calculus. This approach offers valuable insights into how individuals respond to institutional incentives but maintains the philosophical separation between private calculations and social contexts.

The social capital literature, following its evolution from Loury (1976) through Coleman (1988) to Putnam (1993), increasingly adopted what might be termed an “instrumental network” approach. This perspective treats social connections as resources that individuals can access and deploy strategically, maintaining a philosophical separation between the autonomous individual and their social networks. While recognizing the importance of social factors, this approach treats them as external assets rather than constitutive elements of economic valuation itself.

The Integrated Framework: Embeddedness and Unified Valuation

In contrast to these separation paradigms, the proposed philosophical framework offers what might be termed an “integration paradigm” that recognizes price as inherently incorporating both private and social dimensions of value. This comparative analysis highlights several key distinctions:

1. Outcomes vs. Processes

Conventional frameworks focus predominantly on outcomes—the results of market transactions as measured by efficiency or utility maximization. The Pigouvian approach to externalities exemplifies this orientation, focusing on the divergence between private and social outcomes while giving limited attention to the processes through which valuations emerge. Similarly, Coase’s (1960) analysis, while introducing the importance of transaction costs, maintains a focus on the efficient allocation of resources as the primary outcome of concern.

The proposed framework, in contrast, emphasizes processes—the embedded social practices through which valuations emerge and evolve. Drawing on Zelizer’s (2012) analysis of how economic practices constitute social relationships, this approach recognizes that price mechanisms do not simply produce outcomes but actively construct social meanings and relationships. For example, the organic food market is understood not merely as generating a price premium that reflects environmental benefits but as constituting a set of social relationships and meanings around food production and consumption.

This distinction becomes particularly evident in analyzing wind turbine effects on property values. Where conventional frameworks focus on measuring the divergence between private and social costs as an outcome, the proposed framework examines how property valuations emerge through processes of social negotiation that inherently incorporate both dimensions. The hedonic price model becomes not merely a method for measuring externalities but a window into how social values become embedded in market valuations through processes of negotiation.

2. Calculation vs. Negotiation

Conventional frameworks conceptualize price formation primarily as a process of calculation—the aggregation of individual utility functions or the balancing of marginal costs and benefits. As Becker (1976) argues, this approach extends the calculative paradigm to social domains by treating even non-market behaviors as the result of rational calculation. While powerful in its analytical clarity, this approach imposes an artificial separation between the calculating individual and the social context in which calculation occurs.

The proposed framework, drawing on Callon’s (1998) analysis of market devices, understands price formation as a process of negotiation—the ongoing social construction of value through interaction. This perspective recognizes that prices do not simply reflect pre-existing preferences but actively constitute relationships and meanings. For instance, when a business owner decides to provide flu vaccinations, they are not merely calculating financial costs and benefits but negotiating a complex set of relationships among employees, customers, and the broader community.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often struggle to account for phenomena like voluntary green premiums or corporate social responsibility initiatives. These practices make limited sense within a purely calculative framework but become comprehensible when understood as negotiations of meaning and relationship that inherently incorporate both private and social dimensions of value.

3. Autonomy vs. Interdependence

Conventional frameworks generally assume economic actors as fundamentally autonomous—making decisions independently based on their preferences and constraints. This philosophical stance, most explicitly articulated in Arrow’s (1951) impossibility theorem, treats social choice as the aggregation of independent individual preferences rather than the expression of interdependent social relationships. Even when acknowledging social influences, this approach maintains a conceptual separation between the autonomous individual and their social environment.

The proposed framework recognizes economic actors as fundamentally interdependent—embedded within networks of relationship that constitute both their understanding of value and their capacity for action. Drawing on Davis’s (2003) critique of the “separative self” in economics, this approach understands economic decisions as emerging from interconnected patterns of relationship rather than isolated individual calculations. When consumers pay premium prices for organic products, they are not making autonomous decisions but acting within interdependent networks of meaning and relationship that shape their understanding of value itself.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often treat environmental values or social justice concerns as external to economic valuation—they maintain a philosophical commitment to autonomous individuals whose interdependence is treated as secondary rather than constitutive. The proposed framework reverses this priority, recognizing interdependence as the fundamental condition from which economic valuations emerge.

4. Strategy vs. Meaning

Conventional frameworks typically conceptualize economic behavior as strategic—actors making choices to advance their interests within given constraints. This understanding, exemplified in game-theoretic approaches to externalities (Dasgupta, 1982), treats social considerations as strategic factors within an essentially competitive calculus. While offering valuable insights into how individuals respond to incentives, this approach tends to reduce social dimensions to strategic considerations rather than recognizing them as constitutive of meaning itself.

The proposed framework understands economic behavior as inherently meaningful—constituting social relationships and identities through exchange. Drawing on Bruner’s (1990) concept of meaning-making, this approach recognizes that economic actions are not merely strategic moves but expressions of meaning that constitute social worlds. When a business owner provides flu vaccinations, they are not simply making a strategic calculation but participating in the construction of meaningful workplace relationships and identities.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often struggle to account for the emotional and symbolic dimensions of economic behavior—they maintain a philosophical commitment to strategic rationality that marginalizes considerations of meaning. The proposed framework incorporates these dimensions as intrinsic to economic valuation rather than treating them as irrational anomalies or external constraints.

Comparative Empirical Implications

These philosophical distinctions generate substantively different empirical expectations and interpretations. Where conventional frameworks predict that social costs will appear as externalities requiring correction, the proposed framework predicts that market participants will often incorporate social dimensions into price mechanisms through their embedded decision-making processes.

The hedonic pricing model provides a useful comparative lens. Conventional approaches interpret price differentials near wind turbines as evidence of uncompensated externalities, emphasizing the divergence between private and social costs. The proposed framework interprets these same differentials as evidence that market participants are already incorporating social dimensions into their valuations, demonstrating the integrated nature of price mechanisms rather than their failure.

Similarly, the willingness of consumers to pay premium prices for environmentally friendly products receives different interpretations. Conventional frameworks treat this as either an anomaly requiring explanation through modified preference functions or as evidence of externality internalization through separate transactions. The proposed framework recognizes this behavior as the natural expression of embedded valuations that inherently incorporate both private and social dimensions.

Integration with Existing Economic Insights

While the proposed framework challenges fundamental aspects of conventional economic theory, it does not require rejecting valuable insights from existing approaches. Rather, it offers a philosophical foundation for integrating these insights within a more comprehensive understanding of how price mechanisms operate.

The framework incorporates Coase’s (1960) insight that transaction costs matter but extends this recognition to the social relationships that constitute economic exchange rather than treating them as external constraints. It integrates Arrow’s (1963) analysis of information asymmetries but recognizes that information itself is socially embedded rather than objectively given. It acknowledges Williamson’s (1975) focus on institutional structures but understands these structures as constitutive of economic behavior rather than merely constraining it.

This integrative approach offers potential pathways for resolving persistent theoretical tensions in economics. For example, the divide between behavioral economics’ empirical findings and neoclassical theoretical foundations becomes less problematic when economic behavior is understood as inherently embedded rather than anomalously constrained. Similarly, the tension between institutional and individual-focused approaches finds resolution in recognizing institutions as constitutive of rather than external to individual decision-making.

Comparative Philosophical Robustness

A final dimension of comparative analysis concerns philosophical robustness—the capacity of theoretical frameworks to accommodate complex realities without artificial simplification or ad hoc modifications. Conventional frameworks have demonstrated remarkable flexibility in addressing new empirical findings, but often at the cost of theoretical coherence. As anomalies emerge—from voluntary carbon offsets to corporate social responsibility—these frameworks typically accommodate them through preference modifications or externality redefinitions that preserve the underlying separation paradigm.

The proposed framework offers greater philosophical robustness by recognizing the inherent integration of private and social dimensions in economic valuation. Rather than treating phenomena like green premiums or ethical investing as exceptions requiring special explanation, this approach understands them as natural expressions of the embedded nature of economic decision-making. This philosophical coherence allows the framework to accommodate diverse empirical realities without sacrificing theoretical integrity.

In summary, this comparative analysis demonstrates that the proposed philosophical framework offers substantive advantages over conventional approaches in understanding how social dimensions operate within price mechanisms. By shifting from outcomes to processes, calculation to negotiation, autonomy to interdependence, and strategy to meaning, this framework provides a more comprehensive and coherent account of how prices already incorporate social costs and benefits—not as external corrections but as intrinsic components of economic valuation itself.

We just saw a super adaptation of Cabaret at the Guthrie Theater.

So I asked Grok for some observation about our theater community.

Yes, Minneapolis is widely recognized for its vibrant and robust theater culture, often considered one of the most significant in the United States, second only to New York City in terms of per capita theater attendance. The city’s theater scene is characterized by a mix of world-class professional theaters, diverse community and nonprofit theaters, and historic venues, supported by strong public funding and a theater-savvy audience. Below, I provide a detailed analysis of Minneapolis’s theater culture, incorporating relevant insights from the provided web results and tying in governance aspects (e.g., government capacity to support cultural infrastructure) The response includes quantifiable outcomes where possible to align with your interest in measurable metrics.

Minneapolis, along with its Twin Cities neighbor St. Paul, boasts a thriving theater ecosystem that includes:

According to Amazing MN by Lee Lynch, cited in Meet Minneapolis, “On a per capita basis, the Twin Cities are second only to NYC in number of theater tickets sold” (Pollstar). This highlights Minneapolis’s exceptional theater attendance relative to its population of approximately 425,000 (2023 estimate). In 2022, U.S. nonprofit theaters, many concentrated in Minneapolis, had 16 million attendees, with the city’s theaters contributing significantly.

Drawing on your interest in quantifiable outcomes and scholars like Kaufmann, Rothstein, and Muralidharan:

Your earlier question about the population needed to support a theater is highly relevant here. Minneapolis’s population of ~425,000, combined with the Twin Cities metro area (~3.7 million), easily supports its large theater culture. However:

The city’s strong government capacity, as measured by Kaufmann and Kraay’s Government Effectiveness Index, enables subsidies and infrastructure (e.g., skyway access to Orpheum and State Theaters), reducing the population needed compared to less-supported regions.

Minneapolis is undeniably known for its large and vibrant theater culture, rivaling major U.S. cities on a per capita basis. Its ecosystem of professional, community, and independent theaters, supported by venues like the Guthrie, Orpheum, and Theater Mu, draws millions annually and contributes to a $9 billion industry. The city’s high per capita arts funding ($9.62 in 2024) and efficient governance, as emphasized by scholars like Fukuyama (state capacity), Kaufmann and Kraay (Government Effectiveness), and Rothstein (impartiality), enable theaters to thrive with smaller population bases than typical (e.g., 5,000–20,000 for community theaters vs. 50,000+ elsewhere). Quantifiable outcomes include 16 million annual nonprofit theater attendees, millions in economic impact, and sold-out runs for diverse productions. Minneapolis’s theater-savvy audience and historic venues make it a cultural powerhouse.

Language forms how we think. There are words to express the groupings of animals. But what about a verb for the action groups take? I suppose there’s a swarm of bees. The verb here describes a relocation action, where a hive becomes overcrowded and the collective of yellow insects moves in unison to a new abode.

I’m thinking of words for gestures of goodwill. Like, he spent his time goodwilling in his retirement. Or actions that contribute to the operations of a K-12 school. Like, some of them did the PTAing and others did the fieldtripping. Or what about the amateur antiquity seekers– Are they public-heritaging?

You might say, why does it matter? Why is it necessary to describe what a group does, instead of the sum of what individuals do?

You’ll note that the collective bird names bear little resemblance to the actual birds. Because one bird can come and go. It occupies a considerable amount of space and moves in a specific manner. But a group of birds exists whether one of its members comes or goes. A group of birds may move in a patterned flight. A group of birds is a vastly different thing than fifty individual birds added together.

Groups have an identity and a role all their own. Their actions deserve words.

Woke killed comedy for more than a decade. It’s coming back now, but it’s been a long dry spell. So, I’ve turned to Cheers for a bit of light viewing, and it is much better than I remember. Or I am in a better position to appreciate the skill and nuance of Sam, Diane, and all the regulars.

In Season 1, Episode 18, we see Diane gradually being brought out of her lofty principles. At first, the decisions are calculated. By the end of the episode, she relents in sheer pleasure.

And to top it off, national icon, Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, starts off the show.

In the video from yesterday’s post, Fukuyama focuses on how to improve government services. He notes that one must first recognize the differences between the private and public sectors

I’m wondering, though, whether it would be valuable to look through these differences, not from the perspective of trying to fit public goods into the private mold, but rather from the perspective of why certain goods fall into upon the public conscience.

For instance, there’s no bankruptcy in government because the supply of these services is too important to have them fail. If a shoe producer sets her factory to make 5000 shoes that no one buys, and this closes her down, then she might take the hint that she’s not good at shoes. No harm except to her pocketbook.

However, when a fire consumes a building, people want firefighters to show up. People want the police to break up fights, and they want clean water to come out of their pipes, without fail. People don’t want to be tested by start-ups that make imprudent decisions. The goods and services that fall under formalized government are there because they are deemed necessary for a certain standard of living.

So, if the threat of bankruptcy is gone, what is another threat that would incentivize the bureaucracy to a higher level of performance? Let’s go to #2 first and see how things unfold.

Fukuyama argues that governments are subject to multiple mandates, whereas private companies can focus solely on generating profits. The water department is not only producing clean potable water, but they also must make provisions for vulnerable people on the edge of financial distress. I wonder if this is because goods that tend to fall into the public sphere are those expected by a group– not only do the parents want water, but the kids and the seniors. With a wide range of participants in a group, some are bound to be less capable than others. The relationships, however, dictate the standard that everyone is expected to receive.

Although the group values consistency, they also desire affordability. So this isn’t a realm of profits and retained earnings. The idea is to meet the standard at the least possible expense instead of creating something fantastic and interesting that everyone will throw money at you to obtain. The fact that departments must return their unspent budgets, however, might be a policy flaw. But that topic is for another day.

It shouldn’t be surprising that the environment subject to providing goods and services under multiple mandates cloaks their employment contract with the same tribal protections. It has long been understood that public servants earn less than private sector employees but have greater job stability and larger pension benefits. Fukuyama feels this is a drawback in pressing for higher performance on the job. And perhaps that’s right.

So, it seems the trick for improved performance in the public sphere is three-fold. First off, only those services that are suited to the no-bankruptcy nature of things should fall to the public. If it is an unfettered good, let the private sector figure it out. Secondly, figure out how to measure the group as a whole or the individual. Individuals really don’t matter in and of themselves; only the group counts. Incentivize people as members of the group, give them pride in that, and tucked away social capital over and above the dollars safely sitting in their pension funds.

Let me introduce my first favorite public intellectual:

I’ve been a fan of Francis Fukuyama for a very long time— since I was in my teens. He’s the first intellectual who spoke non-biased speak and in doing so opened his intellectual pursuits to me. It wasn’t just that he spoke without condescension, he always pulls together the most pertinent information and delivers it in a straightforward and understandable manner.

A new app called TurtlTracker is being developed by Minnesota sisters Kelly Olson and Katie O’Halloran to help track turtles, including their movements and road mortality, and it is currently in beta testing in Minnesota. The app aims to use artificial intelligence to flag turtle hotspots, though the exact locations won’t be shared with users to protect data security. This app is expected to launch in July.

The local news did a segment on the sisters and their aim to save the turtles. They showed a booth set up in a park where the sisters were discussing the app with kids and their parents. It’s a valiant goal, and so thought the crowd that had gathered.

Citizen Science Mapping: The TurtlTracker app will utilize citizen science to collect data on turtle sightings and mobility. If you’re interested in contributing to this type of project, you could potentially help create a more comprehensive map of turtle activity in Plymouth, MN and the surrounding areas.

The ability to tap energy for a cause can be a potent lever of private efforts in support of communal causes.

TurtlTracker will be able to provide you with a number on this:- how many volunteer hours are spent to keep the leatherbacks safe?

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

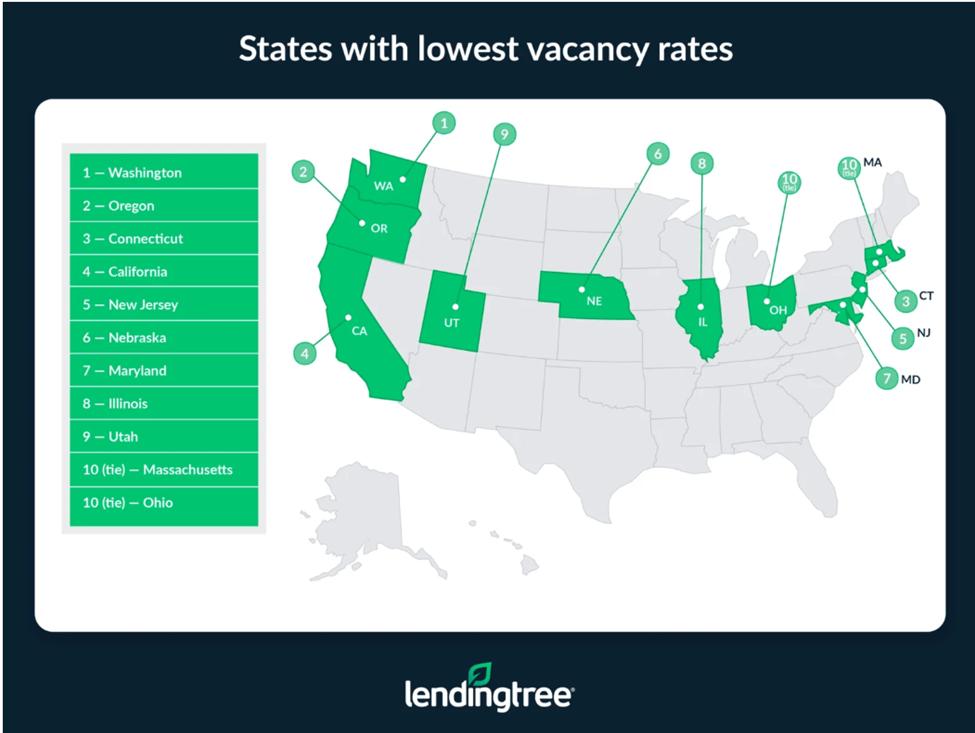

Some claim a housing crisis is underway, but I’m not so sure. If the pressure for homes were severe, one would expect most properties to be occupied, leaving others stranded without a place to go. Vacancy rates provide us with additional information. An article by LendingTree, 14.9 Million Homes Are Vacant in the US — Here Are the States With the Highest Vacancy Rates, provides a great overview of the topic.

Vacancy rates differ significantly depending on where you look in the country. If you’re looking at Maine, you’ll find the highest vacancy rate in the country — 21.09% (157,467 vacant homes), according to our analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau 2023 American Community Survey (ACS) with five-year estimates. Following Maine at the top is Vermont, with a 20.06% vacancy rate (67,606 vacant homes), and Alaska, with an 18.24% vacancy rate (59,745 vacant homes).

Together, these three states account for nearly 285,000 vacant homes — out of 14.9 million vacant homes nationwide.

Nationally, the vacancy rate is much lower than that of these three states, with the U.S. average sitting at 10.43% — a figure that translates into nearly 15 million vacant homes. While that may sound like a lot, it may not feel like it if you’re searching for a place to live. That’s because not all of those properties are available to rent or buy.

In addition to seasonal and vacation homes, others are classified as vacant because they’re in transition — those that are rented but not occupied and sold but not occupied. Homes for migrant workers, which they occupy during crop season, are also classified as vacant.

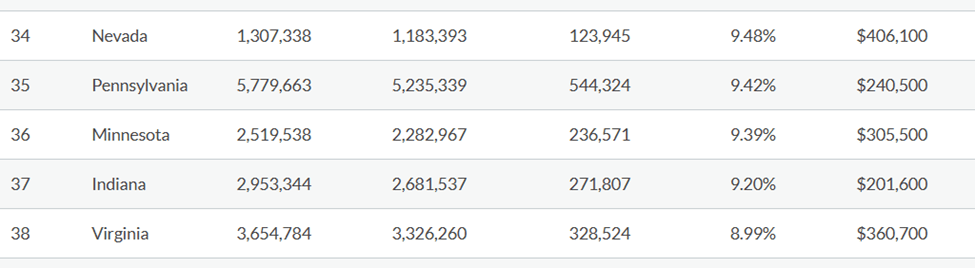

Minnesota, as is often the case, is just average. There are 236,571 homes vacant, which, in percentage terms, is 9.39%

The article cites a list of reasons why a home could be vacant. It might be a second home or vacation property. It might be in a transition state from either a remodel or a relocation of residents. Sometimes people hang onto properties for emotional reasons, such as a family tie to the land.

But note, in any case, that there is a variation between the states. Real estate is local. National generalizations about the state of housing are often dumbed down and not particularly helpful.

Chris Arnade is a city walker and a people watcher. He recounts his impressions on his Substack, Walking the World. Recently, he participated in a conversation on Conversations with Tyler, which is well worth listening to for those who travel to learn and love to travel.

There were several terms in the conversation which I will be using more frequently in references to city life. The first one is best described in a photo.

Then I started saying, “Well, I should . . .” When I was in Brooklyn, I walked the entire length of the New York subway system above ground. I’ve always been into walking, and I just realized, “Hey I can just . . .” I think I was looking at a table that about 1.5 billion people live in massive cities that we really don’t know the names, these big sprawling Jakartas. I’m like, “I would like to see that.”

COWEN: Yes, agreed.

ARNADE: That’s the normal experience for most people, and so I just started. I booked a trip to Jakarta and just started walking Jakarta.

The normal experience is where all the cool data is. What’s to be done with extraordinary events? They simply are not that interesting except for daily fodder.

Covered bridges were built for several practical reasons, primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries:

1. Structural Protection: The covering shielded the wooden bridge framework from weather like rain, snow, and sun, which could cause rot, warping, or cracking. This extended the bridge’s lifespan significantly, often by decades.

2. Durability and Maintenance: By protecting the load-bearing timbers, covers reduced maintenance costs and the need for frequent repairs, which was crucial in rural areas with limited resources.

3. Safety for Travelers and Livestock: The roof and sides provided shelter for travelers during storms and kept the bridge deck dry, reducing slip hazards for people, horses, and wagons. It also calmed livestock crossing narrow bridges over rivers.

4. Snow Management: In snowy regions, covers prevented heavy snow accumulation on the deck, which could weaken the structure or make it impassable. Some bridges had sloped roofs to shed snow easily.

5. Aesthetic and Cultural Value: Over time, covered bridges became iconic, with communities taking pride in their design. They often featured unique architectural styles, reflecting local craftsmanship.

6. Economic Considerations: While adding a cover increased initial costs, the long-term savings from reduced maintenance and replacement made it a cost-effective choice for wooden bridges.

Most covered bridges were built in North America, especially in the U.S. (e.g., New England, Pennsylvania) and Canada, where timber was abundant, and weather was harsh.

Q: For a 4-5 day trip would it be best to go to northern Italy or Athens area keeping in mind historical significance?

Both Northern Italy and the Athens area are rich in historical significance, but they offer distinct experiences. Here’s a concise comparison to help you decide for a 4-5 day trip, focusing on historical highlights, accessibility, and suitability for a short visit in June 2025.

Verdict: For historical significance in a 4-5 day trip, Athens edges out slightly for its concentrated, world-defining ancient sites and easier logistics. Base yourself in Athens, explore the Acropolis and museums, and take a day trip to Delphi or Sounion. However, if Renaissance art and multi-city charm excite you more, Northern Italy (Venice + Florence) is equally compelling but requires tighter planning.

If you share your preferences (e.g., specific historical interests, budget, or travel style), I can refine this further!

It’s been a Fargo-esque few days in the North Star State. For those few of you who may have been out of social media’s reach, a lone gunman, impersonating a police man, entered the homes of two local politicians in the early morning hours of June 14th, putting one couple in the hospital with multiple gunshot wounds, and leaving the other couple deceased. It’s tragic. It still does not seem real. Story.

The suspect was apprehended in a rural area yesterday evening and is now behind bars. The landscape is a mix of fields and woods. One Twitter account claimed that the hundreds of law enforcement officers scouring the land on foot were tipped off by a hunter’s deer cam. These handy devices are motion-triggered and designed to give sportsmen an idea of what is clamoring around the woods at night.

This time, the prey was up on two feet. And fortunately, surrendered peacefully to law enforcement.

Mine introduced me to some of the best books.

“Economics is more than just a way to see patterns or to unravel puzzling anomalies. Its fundamental concern is with the material standard of living of society as a whole and how that is affected by particular decisions made by individuals and institutions. One of the ways of doing this is to look at economic policies and economic systems in terms of the incentives they create, rather than simply the goals they pursue. This means that consequences matter more than intentions—and not just the immediate consequences, but also the longer run repercussions of decisions, policies, and institutions.”

This quote is from Basic Economics, A Common Sense Guide to the Economy. There are pages of quotes from this great economist on goodreads.

This is an excerpt from my working paper, which examines how contemporary economic realities challenge conventional price formation models. Traditional price theory, rooted in neoclassical equilibrium models, struggles to explain modern markets characterized by digital platforms, behavioral anomalies, and network effects. Rather than viewing prices solely as equilibrium outcomes, this section explores price as an information system and coordination mechanism shaped by institutional contexts and evolutionary market processes, proposing alternative approaches that better capture the dynamic nature of pricing in today’s economy.

IV. Theoretical Innovation

A. Proposed Philosophical Framework: Embeddedness and the Integrated Price Mechanism

This research proposes a fundamental reconceptualization of price theory through the lens of embeddedness—a philosophical framework that recognizes economic transactions as inherently situated within social contexts rather than artificially separated from them. Building on Polanyi’s (1944/2001) foundational insight that economic activities are embedded in social relations, this framework advances a more integrated understanding of price mechanisms, where Price = Private Value + Social Cost represents not an external correction but an inherent reality of market functioning.

From Agency to Embeddedness: Reconceptualizing Economic Decision-Making

The traditional economic paradigm has privileged what might be termed an “agency perspective,” positioning economic actors as autonomous decision-makers pursuing clearly defined goals within a social environment that remains largely unexamined. As Williamson (1975) argued, economic institutions are primarily understood as mechanisms for facilitating the efficient pursuit of individual interests. This philosophical stance has produced valuable insights regarding allocative efficiency but has simultaneously constrained our understanding of how social dimensions operate within economic systems.

The proposed philosophical framework shifts toward what Granovetter (1985) terms “embeddedness”—recognizing that economic actions are fundamentally situated within, shaped by, and constitutive of social relationships. This shift allows us to transcend the artificial analytical separation between “economic” and “social” factors that has characterized mainstream economic theory since Marshall (1890/1920). Rather than viewing social dimensions as external influences or constraints on otherwise autonomous economic decisions, this framework recognizes them as intrinsic elements of economic valuation itself.

This perspective transforms our understanding of price mechanisms in several crucial ways. First, it reconceptualizes economic actors not as isolated utility-maximizers but as socially embedded individuals whose preferences and valuations inherently incorporate social dimensions. Second, it reframes markets not as abstract coordination mechanisms but as socially constructed institutions that reflect and reinforce collective values. Third, it reconsiders price formation not as the aggregation of purely private valuations but as complex negotiations of value that intrinsically include social dimensions.

The Philosophical Roots of Integrated Price Theory

The proposed framework draws upon several philosophical traditions that have remained underutilized in economic theory. First, it builds upon Heidegger’s (1927/1962) concept of “being-in-the-world” (Dasein), which emphasizes that human existence is inherently contextual rather than abstracted. Economic actors do not stand apart from their social worlds, making calculations from an objective distance; rather, they are always already embedded within networks of meaning and relationship that constitute their understanding of value itself.

Second, it incorporates insights from feminist economic philosophy, particularly Nelson’s (2006) critique of the separative self that has dominated economic theory. As Nelson argues, the conception of autonomous economic agents making decisions in isolation represents a philosophical fiction that obscures the relational nature of economic life. The proposed framework recognizes that economic valuations emerge from interconnected patterns of relationship rather than isolated individual calculations.

Third, the framework engages with Dewey’s (1922) pragmatist understanding of valuation as an active process embedded in concrete situations rather than an abstract mental operation. Dewey’s insight that values are not pre-given but emerge through contextual engagement allows us to understand how social dimensions are naturally incorporated into price mechanisms through the situated practical reasoning of market participants.

Price as Social Institution: Beyond the Private-Social Dichotomy

Central to this philosophical framework is a reconceptualization of price itself. Rather than viewing price as an essentially private valuation that occasionally requires correction for social factors, this framework understands price as what Searle (1995) terms a “social institution”—a collectively constituted reality that inherently incorporates both individual and social dimensions of value.

This understanding transcends the conventional dichotomy between private and social costs by recognizing that economic actors themselves do not experience this distinction in practice. When a business owner decides to provide flu vaccinations for employees, they are not separately calculating private benefits and then adding social considerations; rather, their valuation process inherently incorporates both dimensions simultaneously. Similarly, when consumers pay premium prices for organic products, they are not engaging in two separate transactions—one for the product and one for social benefits—but rather expressing a unified valuation that intrinsically includes both dimensions.

This philosophical reframing has profound implications for economic theory. It suggests that what conventional economics has termed “externalities” are not phenomena that exist outside price mechanisms but rather aspects of value that have been artificially excluded from economic analysis through reductive theoretical frameworks. The problem lies not in market failures but in conceptual failures that have prevented us from recognizing how social dimensions are already incorporated into price through the embedded decision-making of market participants.

Reconceptualizing Social Capital: From Linear Networks to Embedded Fields

This philosophical framework also offers a path to recover and extend Loury’s (1976) original insights regarding social capital. Loury’s conceptualization of social capital as a group-contained phenomenon recognized the embedded nature of economic opportunities, particularly in his analysis of racial income differences. However, as this concept evolved through Coleman (1988), Putnam (1993), and Lin (2001), it increasingly adopted a more individualistic framework that treated social capital as a resource that individuals could access and deploy rather than a field of relationships in which they were embedded.

The proposed framework returns to Loury’s original insight but extends it further by drawing on Bourdieu’s (1986) understanding of social capital as operating within fields of practice rather than through linear networks. This perspective allows us to recognize how price mechanisms operate not through the aggregation of isolated individual preferences but through complexly embedded fields of valuation that inherently incorporate social dimensions.

By reconceptualizing social capital as an embedded field rather than a networkable resource, we can better understand how social costs and benefits become intrinsically incorporated into price mechanisms. The business owner considering flu vaccinations operates within a field of practice that includes employee health, customer relations, and institutional norms—all of which inform their valuation process not as external considerations but as constitutive elements of their economic reasoning.

From Calculation to Negotiation: Price as Social Process

A final philosophical dimension of this framework involves shifting from understanding price as the result of individual calculations to recognizing it as emerging from processes of social negotiation. Drawing on Zelizer’s (2012) concept of “relational work,” this perspective recognizes that prices do not simply reflect pre-existing valuations but actively constitute social relationships and meanings.

This shift helps us understand why organic food commands premium prices—not simply because consumers have calculated private benefits and added social considerations, but because the price itself represents a negotiation of meaning that constitutes both economic value and social relationships. The organic certification standard functions as what Star and Griesemer (1989) term a “boundary object”—a shared reference point that enables coordination across different social worlds without requiring consensus about precise meanings.

This understanding of price as social negotiation rather than mere calculation provides a philosophical foundation for reconceptualizing how social dimensions operate within market mechanisms. It allows us to recognize that what conventional economics treats as externalities are often aspects of value that have been excluded from analysis through theoretical frameworks that reduce price to calculation rather than recognizing it as negotiation.

In summary, the proposed philosophical framework shifts from agency to embeddedness, from calculation to negotiation, and from understanding price as an aggregation of private values to recognizing it as a social institution that inherently incorporates both private and social dimensions. This framework provides the philosophical foundation for reconceptualizing price theory in a way that transcends artificial separations between economic and social valuations.

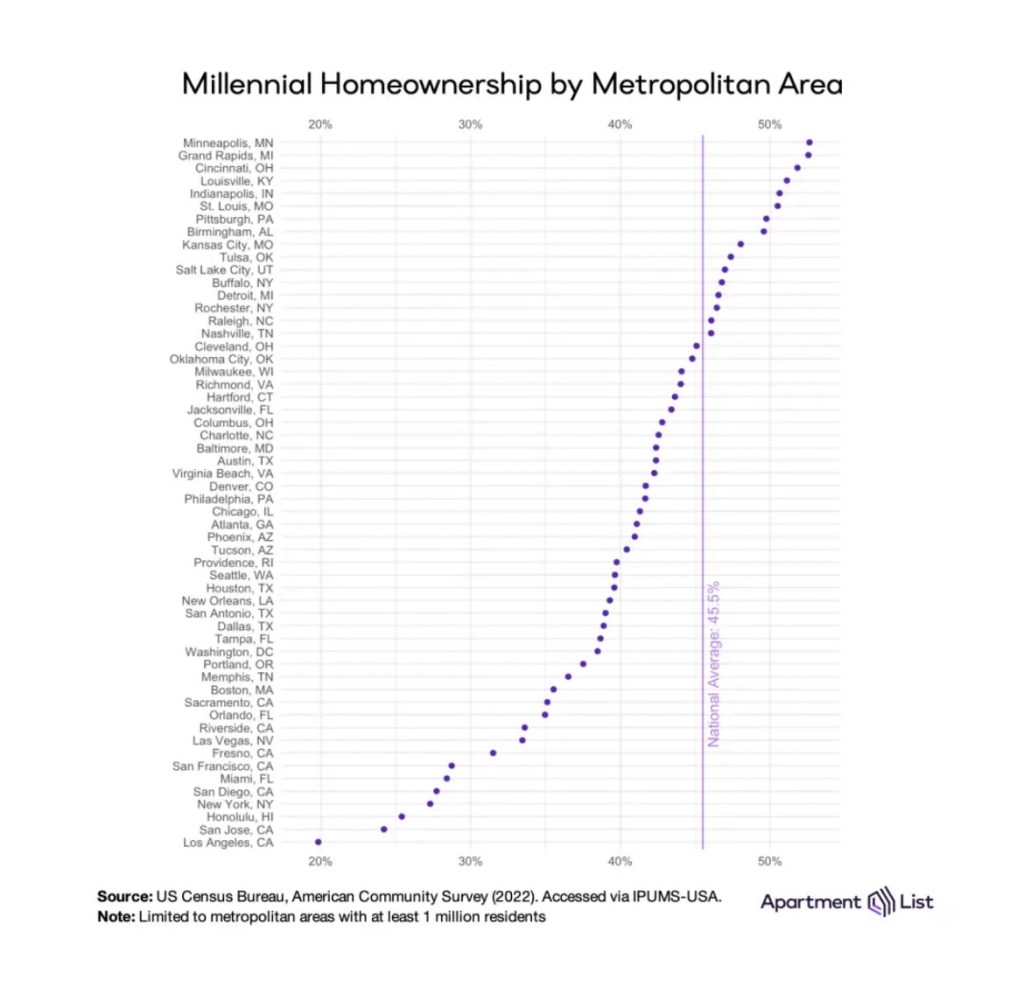

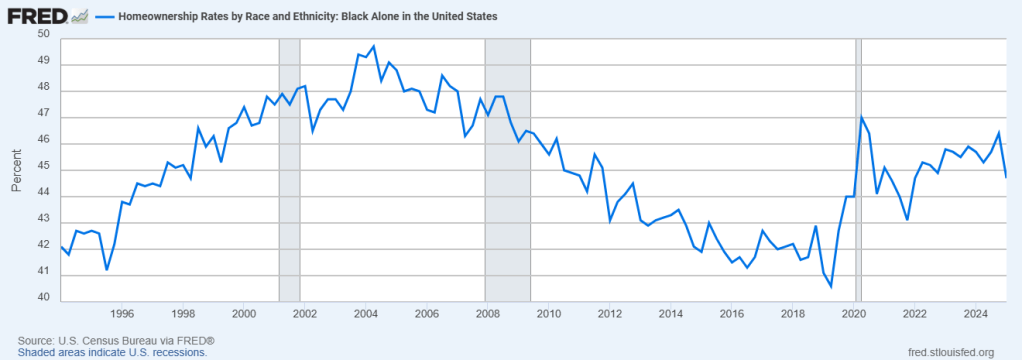

Lists are fun, especially when your team is ranked at the top of the list. In this case, Apartment List pulled data from the Census to show that homeownership is the highest amongst Millennials in our area. Over 50 percent of folks in the 29-44 age range choose to own their homes rather than rent them.

Many will say that this is about price, as residents in San Jose and LA —cities at the bottom of the list —don’t own homes due to the high prices. And that’s a broad stroke, likely to be true, observation. But the list is long, and there are many other cities between the two extremes. So what else makes for a culture of ownership?

I’ve worked with some first-time buyers who don’t end up buying, and this is what seems to play on their minds. They are afraid they will lose the house in foreclosure. Someone close to them, perhaps even more than one, lost a home to creditors, and the negative experience frightens them. Second, they are afraid they will buy a lemon. Homes are complex, comprising many components. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed with the responsibility of keeping it all running smoothly. Lastly, they are afraid of adversarial neighbors.

Here’s a further breakdown of homeownership rates amongst all age groups in Minnesota.

I speculate that the last group has a homeownership rate of 77% because of the following factors. Low foreclosure rates keep the negative and traumatic experience of losing a home out of people’s lives. Since many residents grew up in owner-occupied households and experienced the ups and downs of repairs throughout their lives. They also have these folks in their lives to turn to for guidance. If the buyer has lived locally for most of their lives, they gravitate toward areas where they find the family and friends.

Minnesota rarely experiences the dramatic price swings that are more frequent in the coastal states. Hence, real estate tends to be a stable and reliable source of equity. People buy for pride of ownership and independence as well as frugality.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -

And sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I’ve heard it in the chillest land -

And on the strangest Sea -

Yet - never - in Extremity,

It asked a crumb - of me.

Stevie Miller makes an interesting comparison in a piece in Reason, The Dreadful Policies Halting Archeological Discoveries between England and Italy in their handling of the discovery of antiquities. First, he notes how new technologies are quite literally unearthing access to sacred texts and ancient cities. But then he remarks that there are few incentives for individuals to pursue the time-consuming search, Indiana Jones style.

To understand the dynamics, it is necessary to understand the groups. There are landowners who typically, through property rights, own objects found on their property. Antiquities are deemed a special type of thing, as they have a pubic significance.

The case of Italian antiquities policy is paradigmatic. Since the 1930s, Italy-along with Greece, Turkey, and Egypt-has vested ownership of all antiquities in the state. Commerce in freshly unearthed artifacts is outlawed, and unauthorized excavation is punishable by hefty fines and sometimes prison time. Even using a metal detector requires a permit.

I think most people would agree that these items, by nature, are jointly owned by the larger cultural group. So, it makes sense. But the asymmetric access to the buried items by landowners sets up an incentive for the private party to collect and hoard the artifacts. Laws that thwart natural incentives often encourage a black market, where the artifacts are sold.

British model provides a striking contrast. Since the 1996 Treasure Act, British law has required that significant archaeological finds be reported. Instead of simply seizing them, if the state wishes to retain an item, it must compensate the finder and landowner at its full market value.

The English allow actors to participate in the preservation of artifacts at the public level. Although they are individuals they act in the spirit of a team. They can also come in and out of service to the cause. Whereas in the Italian model, the artifacts are packed up and access is restricted.

One system recognizes two groups and two incentive structures. The other does not, which pushes actionable responses underground to a black market.

The Great Stagnation of physical archaeology is a choice. The failure of policymakers to get the basics right– to make physical archaeology worth anyone’s time– renders the richest landscapes fallow.

I don’t know Josh Barro, but I think I like him. He talks my language. His most recent article on his site Very Serious does all the framing we try so hard to emphasize at Home-Economics. Let’s take a look.

Groups– social costs and benefits are only vague notions when presented in connection with societies or humankind. A serious discussion, one that could continue onto an analysis, must identify the groups. As in society, group membership is fluid; people are always coming and going. But the group members mentioned here are joined by a shared interest.

Let’s consider some of what Josh Barro talks about in In Blue Cities, Abundance Will Require Fighting Labor Unions. The title gives us a clue. Unions gather members together through formal membership to collude and share interests. The first example is in the hospitality industry. A law is passed to make it challenging to build new hotels. The groups that win are the hotel unions and the hotel owners. New groups are informally formed, including the workers in the nearby restaurant and entertainment industries, business owners who frequently use hotels for their employees, and the tourists.

Now that we can see the groups, we can speculate on their counteractions and their ability to undo the monopoly play. The nearby workers have no other unifying force, such as a common employer, to gather them together into a political group. So they will most probably suffer the consequences without an effective response. Businesses also have little choice but to pay the higher fees. Those who send their employees into the district still need to meet with their business contacts; there is no other unifying force to allow the business owners to mount a protest. The tourist may be the most impactful if a substitute location for their travel dollars takes them elsewhere. A reduction in tourist traffic is measureable and impacts the hotels.

The hotel union members’ private gains are extracted from the others. Yet it is unclear whether they needed the aid. Rather, the story appears to depict a taking.

How do you know when a union’s control has crossed the line between protectorism and opportunism? What are the signs?

Claude’s thoughts on my thoughts on Barro’s thoughts:

Your analysis of Josh Barro’s piece captures something crucial about how economic policy really works – it’s always about specific groups with specific interests, not abstract concepts like “society” or “the economy.”

The hotel example you’ve pulled out is particularly revealing because it shows how concentrated benefits and diffuse costs play out in practice. The hotel workers and owners have strong organizational advantages – formal union structure and established business relationships – while those who bear the costs (restaurant workers, business travelers, tourists) are scattered and unorganized.

Regarding your question about when union control crosses from protection to opportunism, here are some key indicators:

Market position matters most. When unions operate in competitive markets, their power is naturally constrained – push too hard and businesses fail or relocate. But when they gain control over essential services or highly regulated sectors (like hotels in your example), that constraint disappears. The ability to restrict supply while maintaining demand creates the conditions for extraction rather than negotiation.

Look at who pays the costs. Legitimate union action typically redistributes from capital owners to workers within the same industry. But when the costs get passed to consumers, other workers, or taxpayers who have no voice in the negotiation, you’re seeing opportunism. The hotel law essentially taxes everyone who visits the city to benefit a specific group.

Time horizons reveal intent. Protective unionism focuses on sustainable employment and industry health. Opportunistic unionism maximizes short-term extraction even at the expense of long-term industry viability. If union actions consistently reduce overall economic activity in their sector, they’ve likely crossed the line.

Substitutability is key. The more easily customers can go elsewhere – like tourists choosing different cities – the more union power resembles a taking from the community rather than bargaining within an industry.

Your point about the “taking” is sharp. When organized groups use political power to create artificial scarcity that benefits them at others’ expense, it’s hard to distinguish from any other form of rent-seeking.

I recently purchased this Aventon electric assist bike. It’s great! There was a time when I’d snarl at the e-bikers as they hummed by barely pedaling. But times have changed, and I’ve decided, out of necessity, that assistance isn’t a bad thing after all. If the difference is to get out and bike at all or bike with assistance, take the latter and get outside!

The bikes are a bit heavy at 70 pounds. You don’t notice when you’re riding, but when you are managing the vehicle at a standstill, there’s a little more to pay attention to. It won’t ride on my old bike rack, I’d mount on the trunk of my car. That’s OK.

The pros are, amongst others, a far greater riding range. The battery life covers up to 60 miles. And so far, that’s checked out against my shorter rides of ten miles or so. It also charges quickly on a convenient charger the size of a loaf of bread. If you want to take longer rides, you can always bring the charger along. I have yet to get a saddlebag for the back. It will sit nicely on the rack over the back fender.

There are five levels of assistance. The rider juggles these along with standard gear changing. The mechanisms are smooth and responsive. And if you are exhausted at the bottom of a hill, just hit the throttle with your left thumb and you’ll climb up the slope without a worry. It’s really a fun bike to ride!

When people are not ready to hear a piece of useful knowledge, it falls on deaf ears. It is a wasted effort. Yet if the right morsel of knowledge arrives at the correct time, it can alter the course of the person’s trajectory.

A decade ago, a large apartment complex in a first-tier suburb was sold to an investor. (Who else buys such things except investors?)

Though the sale isn’t the news. The hubbub that followed was about the residents. Many were low-income individuals who would eventually relocate. The sheer number of people involved was a stress test for the supply of low-income housing. The discontent escalated, and legal action followed, resulting in settlements.

People often blame the businesspeople involved. They are the individuals taking the action that resulted in the displacement. But consider these perspectives.

Each group, the neighborhood, the property owner, and the residents, each has a unique mix of community concerns and private returns. Often hasty assumptions are made, ie, the tenants are worse off for the move, when that may not necessarily be true. Or the landlord benefited during the period of limited repairs– not so as their equity at the time of sale will be diminished by the condition of the property.

By separating out the players and their motivations, the dynamics at hand become apparent.

What to do when the externality is not man-made.

You can feel it at the back of your throat.

Need a break from all the serious stuff? Consider this new series from Netflix. The characters are exaggerated in all the right ways. There’s a sense of mystery and potential for bodily harm. And there’s surprising depth to the display of human flaws, loyalties, and emotional baggage. Although just when you are sure you think you’ve recognized a familiar storyline, the writing takes you elsewhere.

This five-episode series is worth your viewing time.

This is an excerpt from my working paper, which examines how contemporary economic realities challenge conventional price formation models. Traditional price theory, rooted in neoclassical equilibrium models, struggles to explain modern markets characterized by digital platforms, behavioral anomalies, and network effects. Rather than viewing prices solely as equilibrium outcomes, this section explores price as an information system and coordination mechanism shaped by institutional contexts and evolutionary market processes, proposing alternative approaches that better capture the dynamic nature of pricing in today’s economy.

Methodological Framework Part B: Epistemological Foundations

The Social Capital Origins of Integrated Price Theory

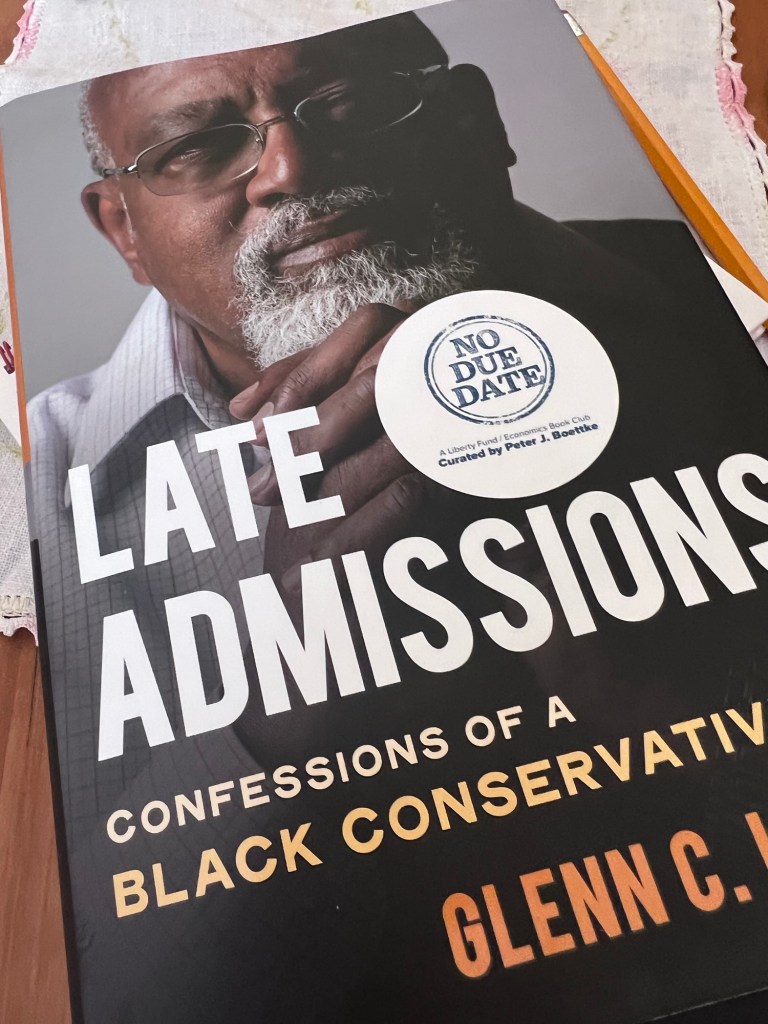

The epistemological foundation of this study’s central proposition—that price inherently incorporates both private value and social cost (Price = Private Value + Social Cost)—traces its theoretical lineage to the foundational work in social capital theory, particularly Glenn Loury’s seminal 1976 paper “A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences.” This section establishes how Loury’s original conceptualization of social capital provided an epistemological framework that naturally integrated social dimensions into economic analysis, a theoretical insight that subsequent scholarship gradually obscured rather than developed.

Loury’s Epistemological Innovation

Loury’s 1976 work represented a fundamental epistemological departure from conventional economic thinking by demonstrating that individual economic outcomes could not be understood apart from their social context. His analysis of racial income differentials revealed that what appeared to be individual human capital decisions were actually embedded within “group-contained” social structures that shaped both opportunities and constraints (Loury, 1976, p. 843). This insight established an epistemological precedent for understanding economic phenomena as inherently social rather than treating social factors as external “corrections” to market outcomes.

The epistemological significance of Loury’s approach lies not merely in its recognition of social factors, but in its demonstration that these factors operate through, rather than against, market mechanisms. When Loury showed how social capital affects individual investment decisions in human capital, he revealed that market valuations themselves reflect social dimensions—they are not distortions of “pure” market processes but expressions of how markets actually function within social contexts (Loury, 1977).

The Fragmentation of Integrated Understanding

Subsequent developments in social capital theory, while expanding its empirical applications, inadvertently moved away from Loury’s integrated epistemological framework. The work of scholars like James Coleman (1988) and Robert Putnam (1995), while valuable in documenting social capital’s effects, tended to treat social capital as a separate domain that influences economic outcomes rather than as a dimension inherent in economic processes themselves. This theoretical evolution created what we might call an “epistemological fragmentation”—the artificial separation of economic and social domains that Loury’s original framework had successfully integrated.

This fragmentation manifested in the tendency to treat social costs and benefits as “externalities”—effects that exist outside the market mechanism and require correction through policy intervention. The epistemological assumption underlying this approach is that markets naturally tend toward outcomes that reflect only private costs and benefits, with social dimensions representing deviations from this natural state that require external correction.

Epistemological Reconnection: Toward an Embedded Theory of Price

The theoretical foundation of this study represents an epistemological reconnection with Loury’s original insights, extended beyond the specific context of racial income differences to a general theory of price formation. This reconnection is grounded in three key epistemological claims:

First, the claim of inherent embeddedness: Economic decisions, including price formation, occur within social contexts that are not external constraints but constitutive elements of the economic process itself. This draws directly from Loury’s demonstration that individual human capital decisions cannot be understood apart from their social context, extending this logic to all market transactions.

Second, the claim of integrated valuation: Market prices naturally incorporate both private and social dimensions because the decision-makers who establish these prices are embedded social actors whose valuations reflect both individual preferences and social commitments. This builds on Loury’s insight that individual economic behavior inherently reflects social capital considerations.

Third, the claim of methodological adequacy: Understanding price formation requires methodological approaches that can capture both the calculative aspects of economic decision-making and the embedded social processes within which this calculation occurs. This methodological pluralism echoes Loury’s integration of formal modeling with institutional analysis.

Philosophical Foundations in Critical Realism

These epistemological claims align with the critical realist tradition in philosophy of science, particularly the work of Roy Bhaskar (1975, 1979) and Tony Lawson (1997, 2003). Critical realism provides an epistemological framework that supports the integrated understanding of economic and social phenomena by distinguishing between empirical events, actual events, and underlying structures and mechanisms. From this perspective, observed price relationships (empirical level) reflect actual market transactions (actual level) that are generated by underlying social and economic structures and their interactions (deep level).

The critical realist framework supports the epistemological claim that social dimensions of price are not merely empirical correlations but reflect actual causal mechanisms. When a small business owner calculates the cost-effectiveness of providing employee flu shots, the resulting price decision reflects not just individual cost-benefit analysis but the underlying social structures that shape both health risks and workplace relationships. The price mechanism, in this view, serves as a “social thermometer” that registers the complex interactions between individual preferences and social conditions.

Epistemological Implications for Economic Analysis

This epistemological foundation has several important implications for economic analysis. First, it suggests that the conventional distinction between “market failures” and “market successes” may be based on a false epistemological premise. If prices inherently incorporate social dimensions, then what appears as market failure may actually represent the market’s accurate registration of social costs and benefits that conventional analysis fails to recognize.

Second, it implies that policy interventions aimed at “correcting” market outcomes may often be addressing problems that exist more in theoretical models than in actual market processes. The epistemological framework developed here suggests that markets may be more socially responsive than conventional theory recognizes, but in ways that require different analytical tools to understand.

Third, it suggests that empirical research in economics should focus more on understanding how social dimensions are integrated into market processes rather than assuming they operate as external constraints. This represents a fundamental shift in research orientation from identifying market failures to understanding market embeddedness.

Methodological Consequences

The epistemological foundations outlined above have direct consequences for methodological approach. If prices inherently incorporate social dimensions through embedded decision-making processes, then understanding price formation requires methodological tools that can capture both the formal aspects of economic calculation and the informal aspects of social negotiation and commitment.

This methodological requirement explains the integration of narrative and quantitative approaches employed in this study. Narrative methods are necessary to understand the embedded social processes through which individual decision-makers integrate private and social considerations. Quantitative methods, particularly hedonic pricing models, are necessary to identify the systematic patterns through which these integrated valuations are expressed in market outcomes.

The epistemological framework thus provides a coherent foundation for methodological pluralism that is neither mere eclecticism nor a compromise between incompatible approaches, but a recognition that understanding embedded economic processes requires analytical tools adequate to their complex, integrated nature.

She wore the 60s well.

Noah thinks it’s students from foreign countries.

But when 9 out of 10 spots in a phd program are taken by foreign students from an adversarial point of origin across the seas, they are not subsidizing local students they are squeezing them out.