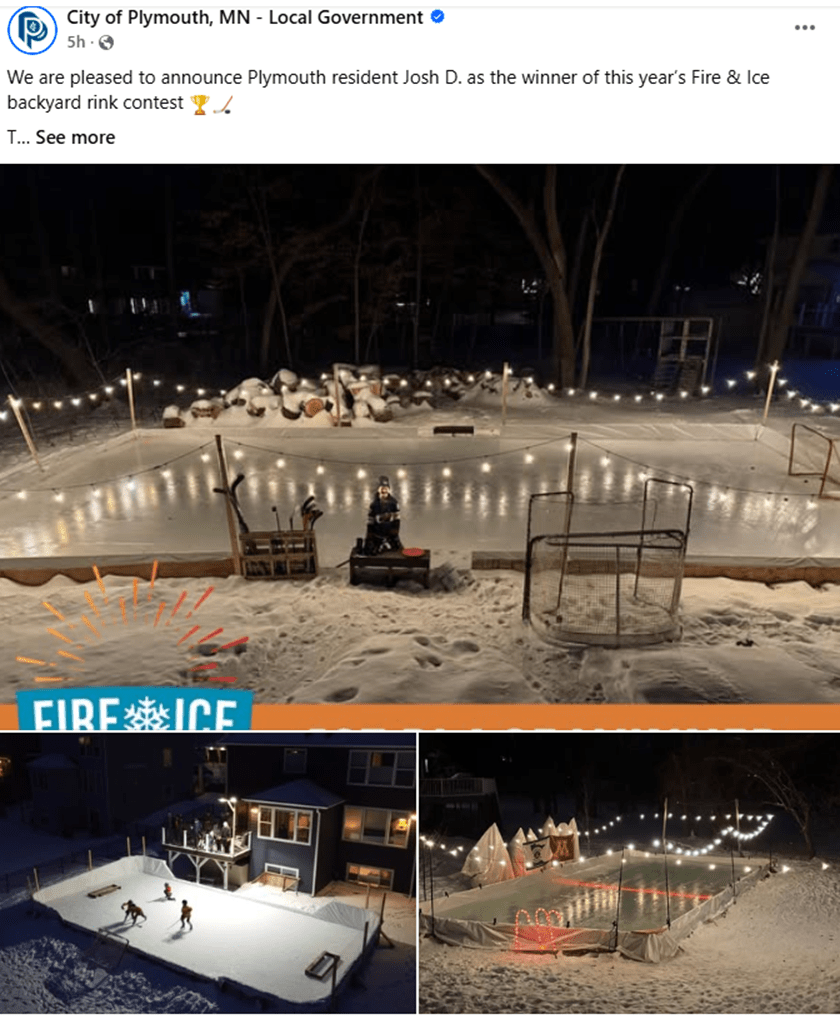

You can compete for the best backyard ice rink.

Support youth athletics, invite the neighbors over, and make your town proud.

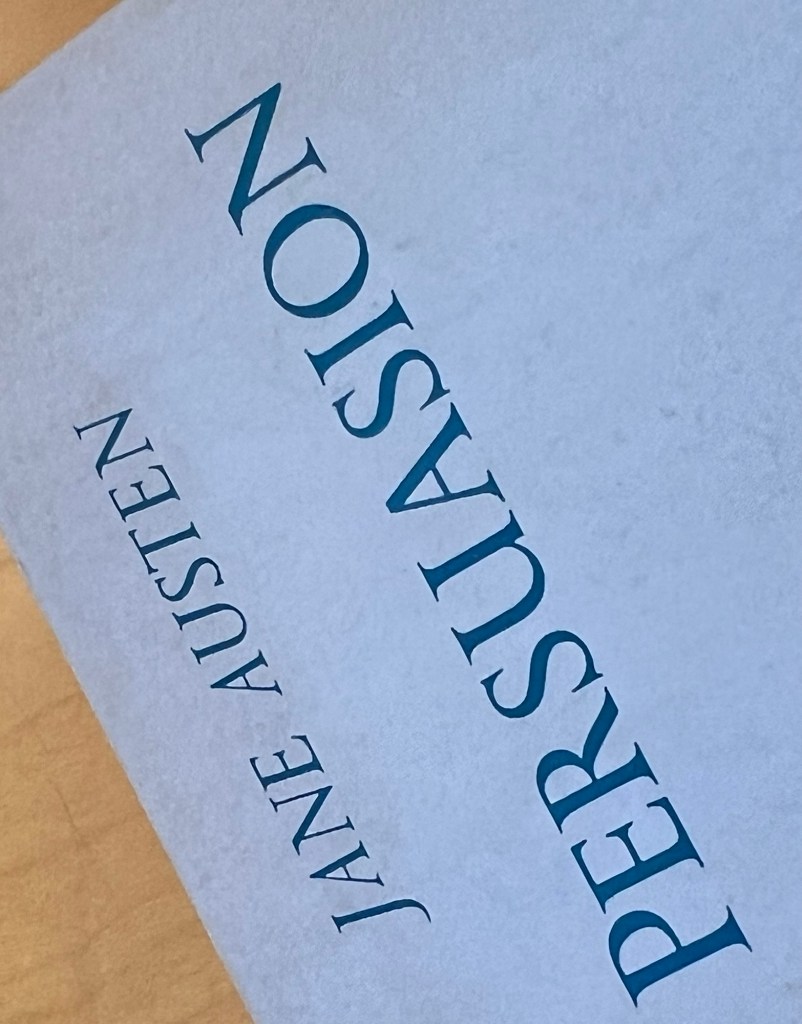

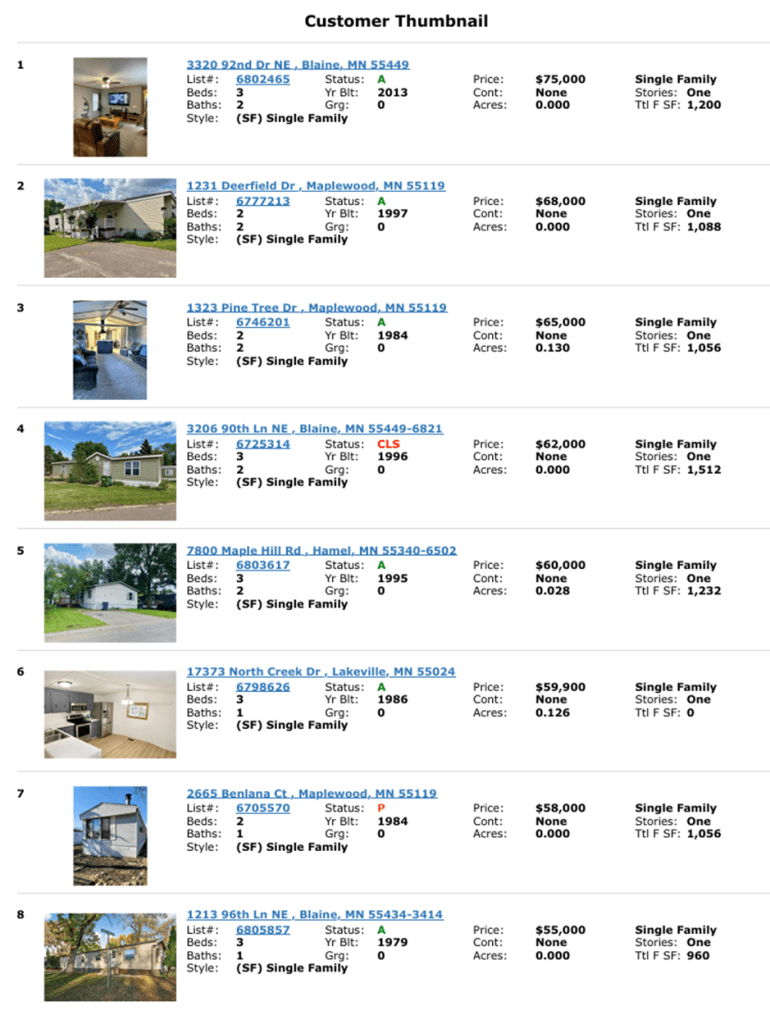

Searching for value

You can compete for the best backyard ice rink.

Support youth athletics, invite the neighbors over, and make your town proud.

It’s been hard to read all the opinions about our fair state lately. Most people get some of it or all of it wrong: the groups, the geography, the factions, and the issues. In a post yesterday at The American Mind, Ayaan Hirsi Ali delivered the most insightful piece I’ve read so far. If you are from the West, you might want to read her book Infidel first as it best explains the depth and commitment of tribal society. The article, Minnesota’s Post-Assimilation Realty, details a concoction of groups moving together to create a powerful incentive package for what will probably be the largest theft of Federal dollars in US history.

Let’s pull apart the components of human action. Hirsi Ali introduces the first player.

Somali society is organized around the clan. Loyalty is not abstract, nor is it civic. It is biological and binding. The individual exists only insofar as he serves the group. Protection, marriage, honor, silence, and punishment are governed by this code. Obligations flow inward, sanctions flow downward. The clan precedes the individual and outlives him.

Instead of assimilating into the various groups of civic life, their group remains closed. Their action is based on internalizing benefits to themselves and keeping outsiders at bay.

Extract what can be extracted, and when the host weakens, move on. This is adaptation in its purest form. But it is fundamentally incompatible with modern civic life, which depends on social trust rather than blood ties.

Edward Banfield called this phenomenon “amoral familism.” Loyalty inward, indifference outward. Where it dominates, corruption is not a deviation from the system. In truth, it is the system. Public institutions become spoils to be captured, law becomes negotiable, and accountability vanishes.

But no group, in a country as large as the US, can operate solo. There are great over-arching institutions at play where activities will collide in action and deed. So who else is clearing an open path from other conflicting objectives?

Minnesota hosts a dense network of Islamic councils and advocacy groups dominated by Somali leadership. Nationally, the pattern is expanding. Each success is framed as inclusion, which is insulated from scrutiny by the language of civil rights. And each success advances a narrow, disciplined agenda that is deeply anti-modern.

The Democratic Party completes the triangle. Immigration shifted from policy to identity. Enforcement became immoral, and illegality was reframed as victimhood. The result is an unmistakable pattern of activists obstructing federal officers, officials retreating from their duties, and a party increasingly reliant on ethnic blocs it cannot discipline without alienating its base.

The common man (and woman) also has a role to play. In fact, they are now playing a role in the unraveling of this decade-long taking. But for so many years, the workers in Health and Human Services, the neighbors who noted empty daycare centers and so on, were silenced by political pressure. When the choice came between being a whistleblower and maintaining their social or workplace position, they chose to stay the course. Perhaps because they felt it would all be for naught. And perhaps they were right.

Read the whole piece. And all the while think about the structures, both in terms of people and their actions, and think about where liberalism was derailed.

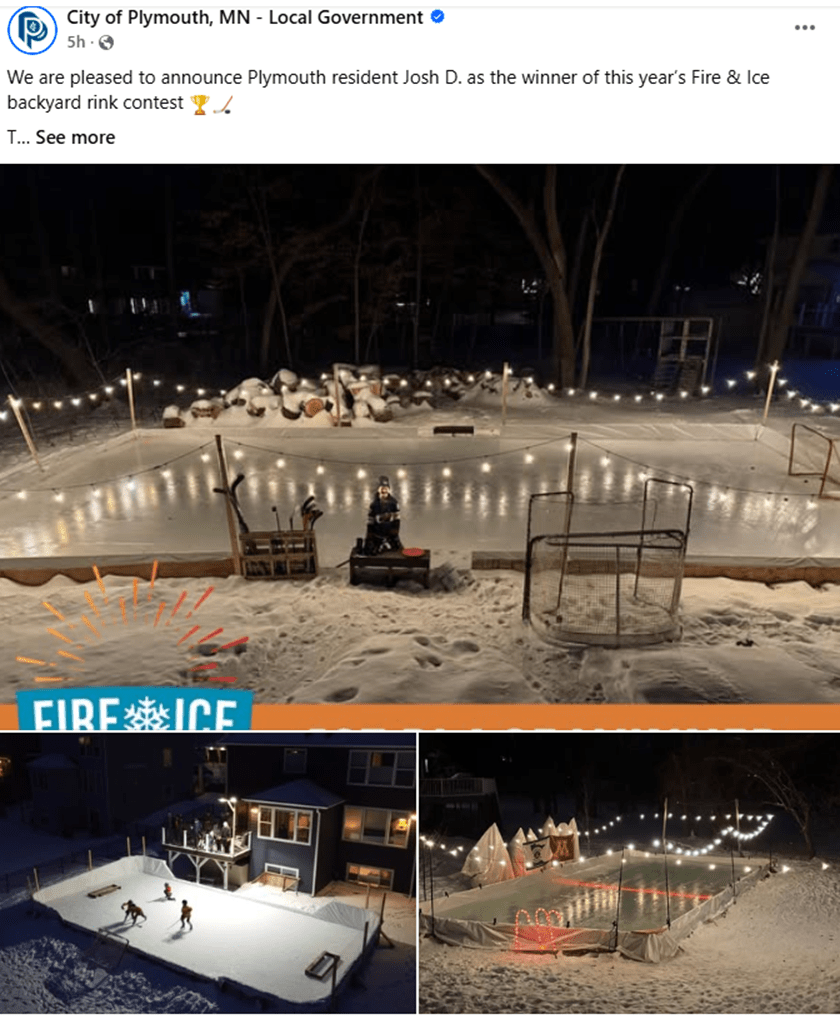

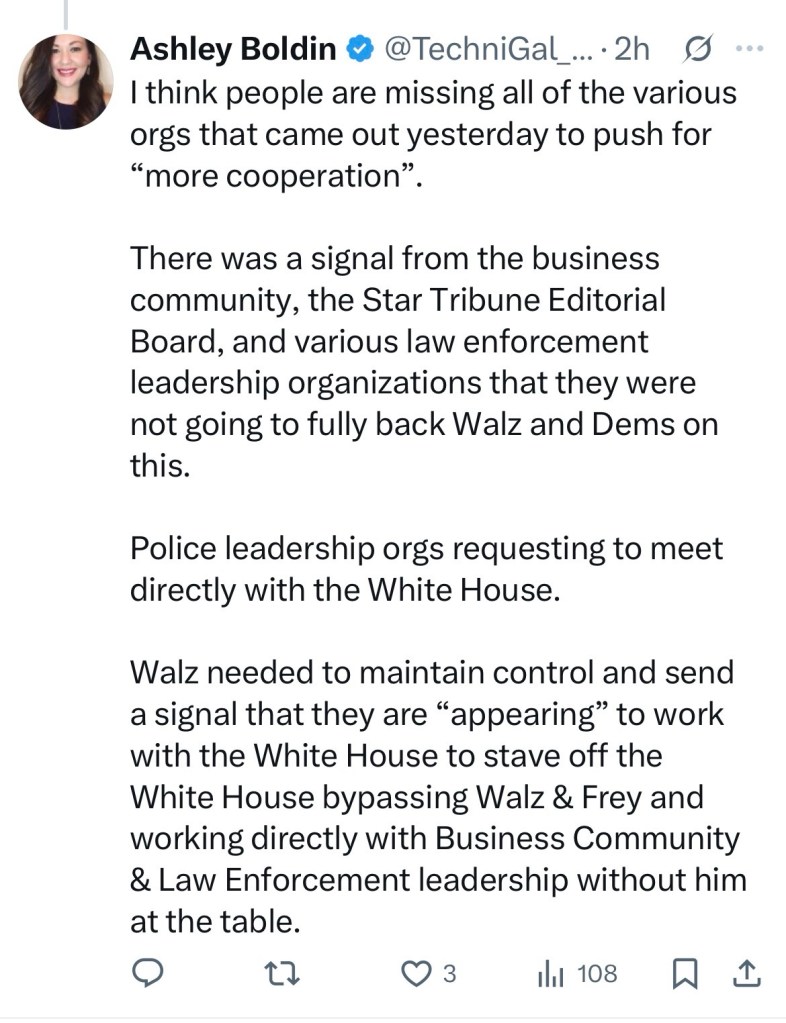

This is a great post for identifying players among the parties with an interest in calm returning to the streets in the central city.

Interestingly, these groups are present in most all communities, large and small.

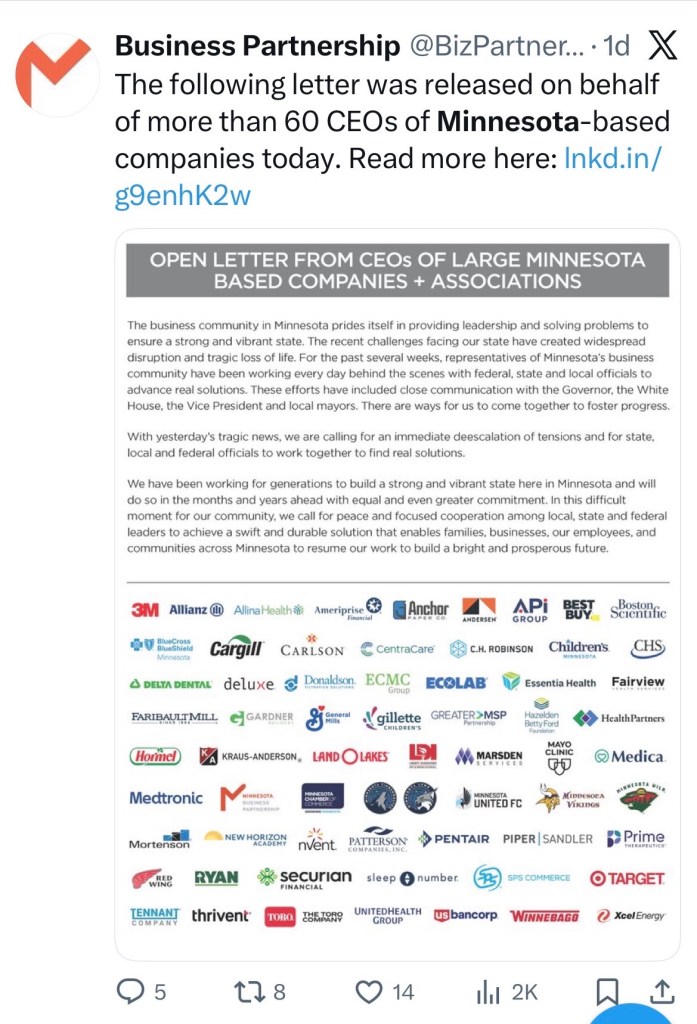

The 60 business signed and posted a request for further cooperation. Note the neutral tone.

The editorial board of the local newspaper also called for a resolution.

Interestingly, the law enforcement folks went directly to the White House. Anyone following along with the conflict five years ago saw the effects it had on this, very necessary, segment of our communities. Their desire to make a direct appeal is understandable.

Each group’s ability to succeed in their duties and objectives have been crimped by the unrest between local and federal officials. But taking a stand can have tremendous costs. For good reason, all of these components are weighed out before action is taken.

It can be an unsuspecting player. Not one of the mighty forefront actors, digging in and refusing to back off. So small are they that they may never be recognized for their role. I say it will be the neighbors.

We’re talking about a very small geography, designated byperhaps a three-quarter-mile radius, taking the brunt of all this hyped-up activity. It must be exhausting. At some point, people say enough. But not out loud. Not where it can be filmed or recorded, but in the anonymity of the group. There will be a small signage. Warnings. Requests for no further contact.

That’s what happened five years ago. Slowly, the baskets of food, goods, and beverages dissipated. There was no fanfare, but small signals in facial expressions or shrugs expressed that the tents in the park had overstayed their allotted time for public use. Upon approaching a classic six-unit brownstone, one might only read the formal Do Not Disturb sign while standing at the entrance.

In the end, people want to live their lives in peace. They wish to be free to go to work, earn a paycheck, and bring it back to share with their families in pursuit of their individual desires. People seek ot balance their freedoms, not relinquish it all to others.

The neighbors will pull the plug.

When the audience has seen the film before.

I wonder if Cass would agree: Liberalism is not fundamentally a fixed political ideology or a contingent historical doctrine; it is an enduring aspiration for the human condition itself—one that seeks to cultivate societies where individuals can pursue diverse visions of a good life, free from arbitrary coercion, amid mutual respect, pluralism, and institutions that safeguard dignity and self-governance.

I feel like Sunstein is would say freedom of speech is a necessary condition for liberalism. If man is to get along in society then there is a need for pluralism, for an admission that others, with other ideas, will group together and their choices as a path to freedom are to be respected. Thus, it is necessary to be able to speak freely about differences and similarities in the practical ways when people live side-by-side. In fact one might even say that free speech illicits a competitive pluralism where the investigation of others and a distinction of differences sets up a truth-finding for each.

We need stories

So I asked: Compare and contrast the substance of the ideas and the context in which they are presented between Cass Sunstein On Liberalism and Matt Yglessias recent posts on Liberalism on his Substack Slow Boring.

And here are some of excerpted reply.

Both Cass Sunstein and Matt Yglesias present liberalism as a broad, pragmatic framework rooted in core values like freedom, pluralism, and the rule of law, but they emphasize different aspects and respond to distinct critiques. Sunstein’s work, primarily through his 2025 book On Liberalism: In Defense of Freedom and related Substack posts, offers a philosophical and historical defense, portraying liberalism as a “big tent” that unites diverse thinkers from John Stuart Mill and Friedrich Hayek to Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama. He defines it via a “holy trinity” of freedom (e.g., speech, religion, property), pluralism (respect for diverse ethnicities, religions, and ways of life), and the rule of law, extending to human rights, security (freedom from fear, echoing FDR’s Four Freedoms), democracy, and “experiments of living” where individuals pursue varied paths without coercion. Sunstein incorporates economic elements like free markets with regulation, FDR’s Second Bill of Rights for social and economic guarantees.

For Sunstein, liberalism is not static but actively constructed, a “fighting faith” that promotes innovation, fairness, and self-correction, making it essential for freedom and self-government amid modern threats.

…..

In contrast, Yglesias’s recent Substack series on Slow Boring (spanning late 2024 to early 2026) takes a more policy-oriented, U.S.-centric approach, framing liberalism as pragmatic technocracy tied to Enlightenment roots like John Locke and Adam Smith, emphasizing individual rights, non-radical governance, and impartial benevolence (e.g., evidence-based policies that benefit broadly without favoritism).

…

Similarities in substance include a shared emphasis on pluralism, freedom, and pragmatism—Sunstein’s “experiments of living” aligns with Yglesias’s technocratic impartiality—and both see liberalism as adaptable, blending markets with social protections (e.g., Sunstein’s FDR-inspired guarantees; Yglesias’s public order as progressive). They reject extremes: Sunstein critiques illiberal left/right; Yglesias warns against socialist purges or cosmopolitan overreach.

From The Road to Wigan Pier-

On the day when there was a full chamber-pot under the breakfast table I decided to leave.

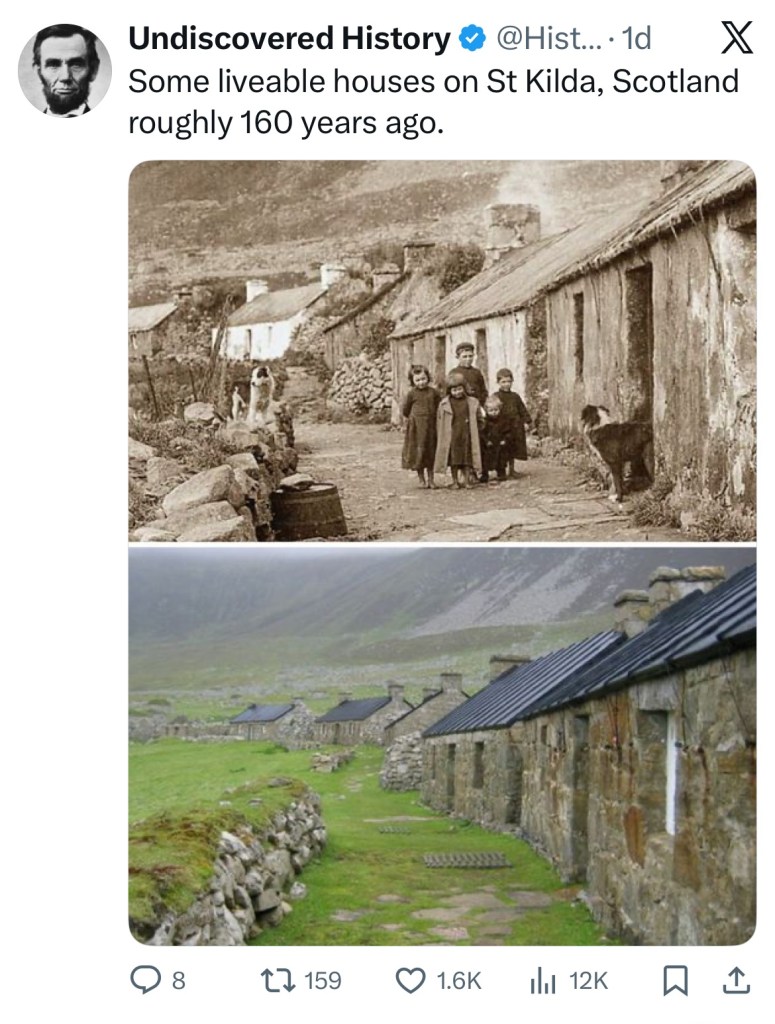

Orwell, writing in 1935-1937 goes into great detail about distressed housing. Here is an insight.

I have noted ‘Landlord good’ or ‘Landlord bad’, because there is great variation in what the slum-dwellers say about their landlords.

I found – one might expect it, perhaps – that the small landlords are usually the worst. It goes against the grain to say this, but one can see why it should be so. Ideally, the worst type of slum landlord is a fat wicked man, preferably a bishop, who is drawing an immense income from extortionate rents. Actually, it is a poor old woman who has invested her life’s savings in three slum houses, inhabits one of them and tries to live on the rent of the other two – never, in consequence, having any money for repairs.

It’s always neglected repairs that do a handsome home in.

This example of a kindness, in the implementation of a rule, can be found in Sunstein’s book On Liberalism.

Compare, for example, a mandatory retirement law for people over the age of seventy-five with a law permitting employers to discharge employees who, because of their age, are no longer able to perform their job adequately. If you are an employee, it is especially humiliating and stigmatizing to have employers decide whether you have been rendered incompetent by age. A rule avoids this inquiry altogether, and it might be favored for this reason even if it is both over- and underinclusive. True, it isn’t exactly wonderful to be told that you have to retire because of your age, but if a rule depersonalizes the situation, then it has significant advantages. Or consider a situation in which officials can give out jobs at their discretion, as compared with one in which officials must hire and fire in accordance with rules laid down in advance. In the first system, applicants are in the humiliating position of asking for grace.

So much of the chatter in the public square, often inflammatory, takes only one piece of an event and amplifies its negative consequences. Or portrays the actor in an unnaturally beneficial light. Rarely if ever are the two sides that led to choices aired out in the fashion quoted above. Often the this is intentional, to win over an audience.

But this type of provocation is not kind or right or productive. If one desires the most favorable outcome, a more insightful analysis of the whole picture is desirable.

Perhaps it is when people are keeping their opinions to themselves that an honest sifting through of the alternatives occurs. Mostly norms are in play here, in the quiet light of personal judgements and sacrifice.

Today’s world is ruled by emotional triggers and half-truths. Post a photo of a drama scene and then just tell half the story. It works for a while, but eventual people get wise to it. The truth shines with resilience.

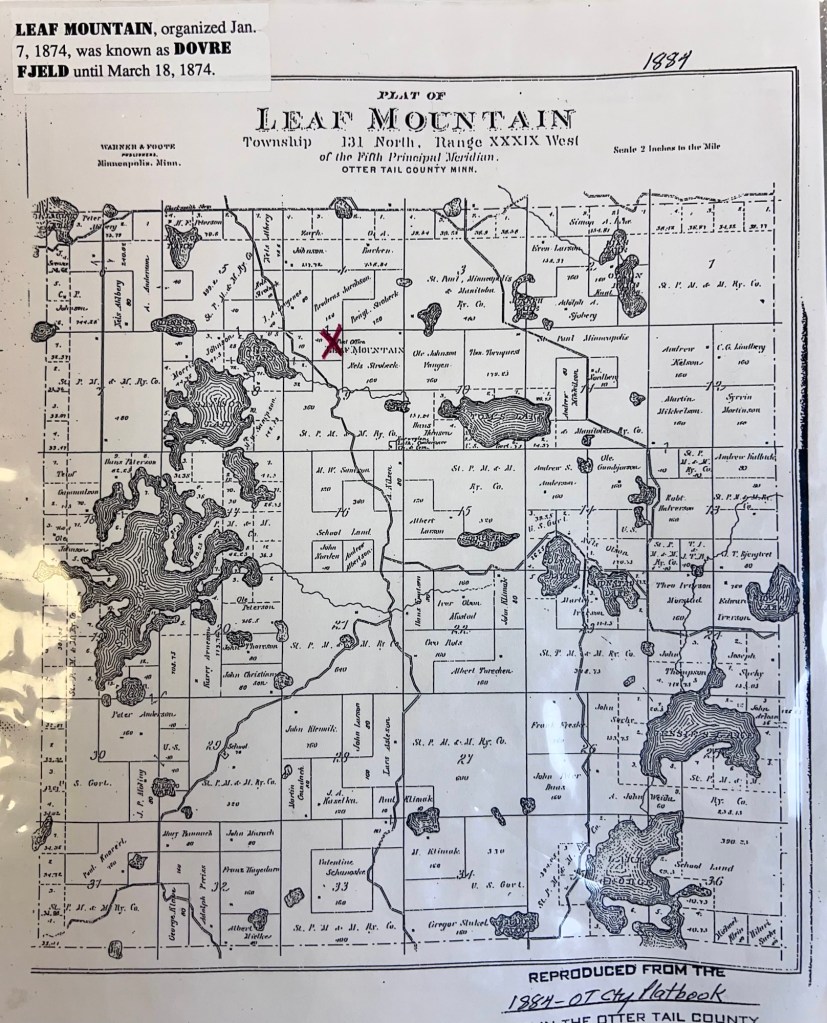

I had heard about this show a while ago, and I am glad to now get to watching it. When I was quite young, we visited Tehran, but the depiction here is of a far larger and more sophisticated city. We also drove over the mountains to the Caspian Sea, and I think of that every time a panoramic shot of the urban skyline is backdropped by the Alborz.

The plot and action in the series are snappy and fairly unpredictable. There’s a nice tension of intrigue without too much violence. The two younger lead actors, Tamar and Milad, are excellent. They remind me of the Iranians students who were at boarding school with me in the late 70s.

There’s a lot to like about this series.

Here are key words and phrases commonly used to highlight the contrast between a philosophical approach (abstract, conceptual, theoretical, reflective) and an operational approach (practical, applied, concrete, implementation-focused). These draw from philosophy, political theory, methodology discussions, and related fields like liberalism debates.

Highlighting the Philosophical Approach

• Abstract / abstraction

• Theoretical / theorizing

• Conceptual / conceptual framework

• Ideal / ideal-type / idealized

• Normative / value-oriented

• Principled / principle-based

• Speculative / reflective

• Foundational / foundational principles

• Visionary / inspirational

• Manifesto-like / declarative

• Big-picture / overarching

• North Star / guiding ideal

• Philosophical defense / justification

• Thought experiment / hypothetical reasoning

• Meta-level / meta-theoretical

Highlighting the Operational Approach

• Concrete / concretization

• Practical / pragmatism / pragmatic

• Applied / application-focused

• Implementation / implementable

• Operational / operationalizable

• Action-oriented / action-focused

• Step-by-step / procedural

• Toolkit / how-to / blueprint

• Policy-oriented / policy design

• Institutional / reform-based

• Executable / hands-on

• Measurable / testable / empirical

• Grounded in reality / context-specific

• Methodological / technique-driven

• Instrumental / cause-and-effect focused

SUNSTEIN: Low probability (that liberalism is self-defeating). The likelihood is that

1:04

we’ll be undermined by anti-liberal and illiberal forces, not self-undermining. I think it’s fair to

1:11

say or to worry that liberalism doesn’t create the conditions for its own self-perpetuation,

1:18

so it’s not as if it’s self-undermining, but it doesn’t necessarily maintain itself. The reason is

1:24

that a society that is flourishing needs a lot of stuff in it, including norms of cooperation, norms

1:32

of charity, norms of mutual support. Liberalism, in my view, doesn’t undermine those things,

1:39

but other forces can undermine them, and it’s not clear liberalism has the resources to respond

1:45

COWEN: When you say other forces, do you mean hostile foreign powers? Or there’s something illiberal in societies that is not sufficiently driven out by liberalism?

1:53

SUNSTEIN: I think there’s something illiberal in the human heart.

In these first few minutes of this exchange between the irreplaceable Tyler Cowen and famed legal scholar Cass Sunstein, the sketch of timbers supporting liberalism as a way of life is laid out. The structure must be conducive to all the stuff society needs. The boards must be placed in such a way as to allow the rules to expand out while finding a tension so as not to collapse on each other. The builders need resources, in the form of materials and their labor.

But be aware! The biggest detractor may reside in the human need to hide things from ourselves.

Liberalism seems straightforward. Individuals are meant to live their lives freely. They flourish when they can follow their ambitions, or talents, or desires for a quiet life. As long as they do no harm to others, people left to their own devices can lead good lives.

All this is fine and good. But of course, we don’t live alone. We live with others. And it is at the juncture of protecting the desire for the self and the duties to the group that friction seems the most keen.

It’s perfectly acceptable for spouses to assign their liberties to each other. One takes care of pecuniary matters while the other looks after the relational part of the family, which is a common division. But sometimes the first is caught saying, “I own it all,” and the other is planning without a thought for the other. After a decade or two, one forgets what the other does for them. Slowly, without gratitude, all the small tasks enabling the freedoms they cherish are taken for granted.

The public and private often evolve into a crisis of duty.

Children easily take for granted the investments their parents made in their upbringing, especially in the US. It is easy for them to minimize what was done and begrudge them beneficial attention in their later years. Neighborhood dwellers take for granted the civic do-gooders who are responsible for small but useful things like stop signs and play lots. Volunteering to maintain or perpetuate shared services is thought of as optional.

And then, coming at the friction from the other angle, there are the enforcers. Those who wish to make every norm a rule. Instead of contributions made in sync with people’s time and talents, they wish to meter it all out and pass the collection plate with vigilance. The spirit of the exchange is ruined. Instead of thankful for the effort, people are resentful for the absence.

Liberalism maneuvers best along a framework for optimal execution. Liberalism needs a framework to avoid undermining itself from the illiberal tendency residing in most human hearts.

Liberals believe in kindness, humility, and considerateness. They like this statement, often attributed to Lincoln: “I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.” Liberals know that kindness, humility, and consid-erateness can be challenging to cultivate.

Trump has a plan—

“I am instructing my Representatives to BUY $200 BILLION DOLLARS IN MORTGAGE BONDS. This will drive Mortgage Rates DOWN, monthly payments DOWN, and make the cost of owning a home more affordable,” Trump wrote.

Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte said on X that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will execute the purchase.

The combined cash and cash equivalents listed on the two firms’ balance sheets in their third quarter earnings reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission was less than $17 billion as of September 30.

Pulte in a phone call to Reuters said the two agencies had “ample liquidity” to carry out Trump’s order, including nearly $100 billion in available funds at each entity.

Full article from Reuters.

Red Eye (2024 thriller series) is a gripping six-episode miniseries starring Richard Armitage as Dr. Matthew Nolan, a British surgeon accused of murder in Beijing, and Jing Lusi as DC Hana Li, the tough London officer escorting him on a red-eye flight back to China. Supporting standout Lesley Sharp plays MI5’s sharp Director General Madeline Delaney.

The plot unfolds aboard the overnight Flight 357, where passengers begin dying mysteriously, forcing Hana to question Nolan’s guilt amid a larger international conspiracy involving political deals and assassinations.

I quite enjoyed the fast pacing that keeps viewers hooked with constant twists, the claustrophobic airplane setting amplifying tension like a modern Agatha Christie mystery, and strong lead performances—Armitage’s charismatic vulnerability and Lusi’s grounded determination.

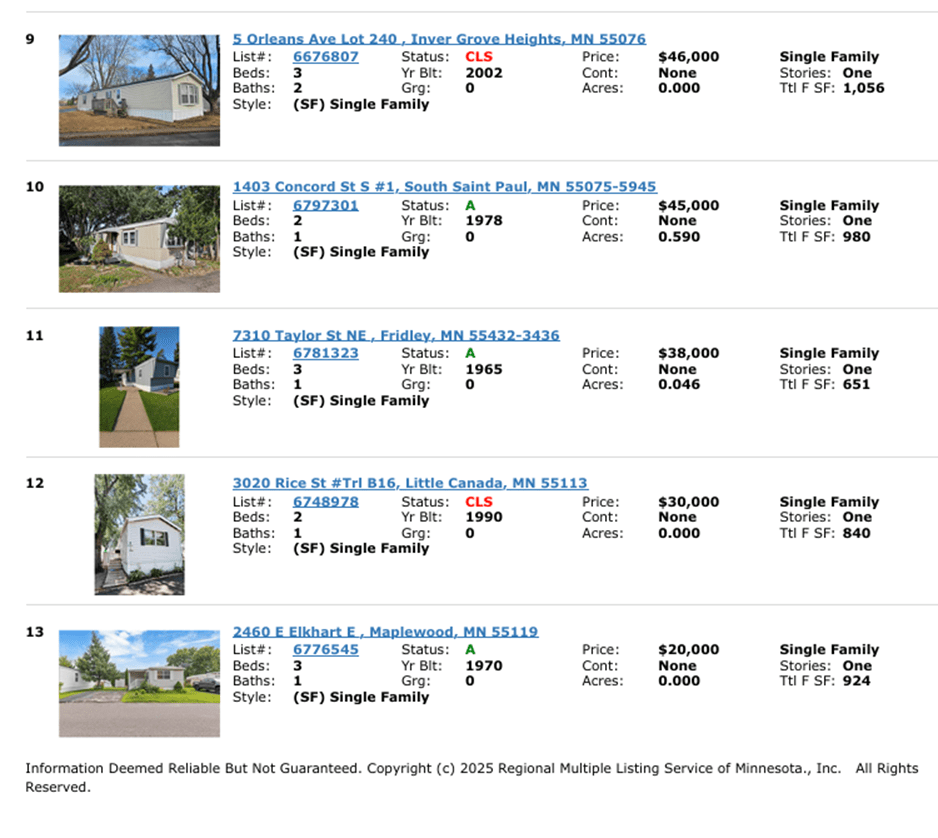

The Homestead Act of 1862 was a public initiative to make land in the middle of the US available to settlers at a very low fee. It encouraged the westward expansion by allocating 160-acre parcels of government-owned land to those who agreed to live on it for five years, build a home, and cultivate the land. By granting ownership after fulfilling these requirements, the US essentially gave away millions of acres to individuals who could prove up their claims.

This policy hinged on a belief that one could turn labor into assets. The government asked people to take their families into the wilderness, far from protective services, to live in caravans or sod houses until they were able to build little cabins, to clear land of growth and turn the soil into protective crop acreage. This exchange offered little in way of immediate return. And the most successful groups turned out to be from cultures of strong family networks for support and a willingness to live frugally in anticipation of a better future.

In truth, the bargain entailed even more. The government was basically asking people to not only see to their own needs on their claim, but to collaborate with neighbors in townships and see the roads get built, and the one-room schoolhouses be completed. In exchange for 160 acres of private property, sweat and toil had to also be dedicated to transportation infrastructure and provisions for education. These early settlers had to have had an enormous desire for a homesite.

I don’t know if such a government program would be successful today. It seems like a tall order. Yet it would be helpful to know at what point the average citizen can be energized to volunteer their labor in support of public infrastructure or support. When are they energized to provide aid in response to a neighboring disaster? What severity of wrongdoing triggers the impulse of an observer to overcome possible whistle-blower costs and report? Where are their public goods ready to be provided spontaneously and who can match that need with their labor?

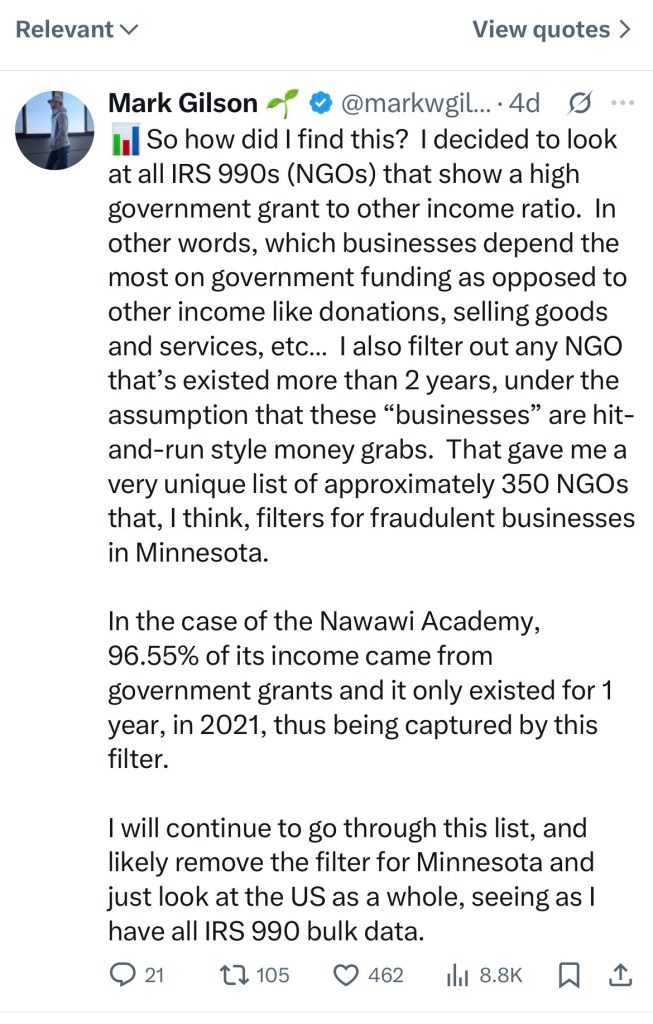

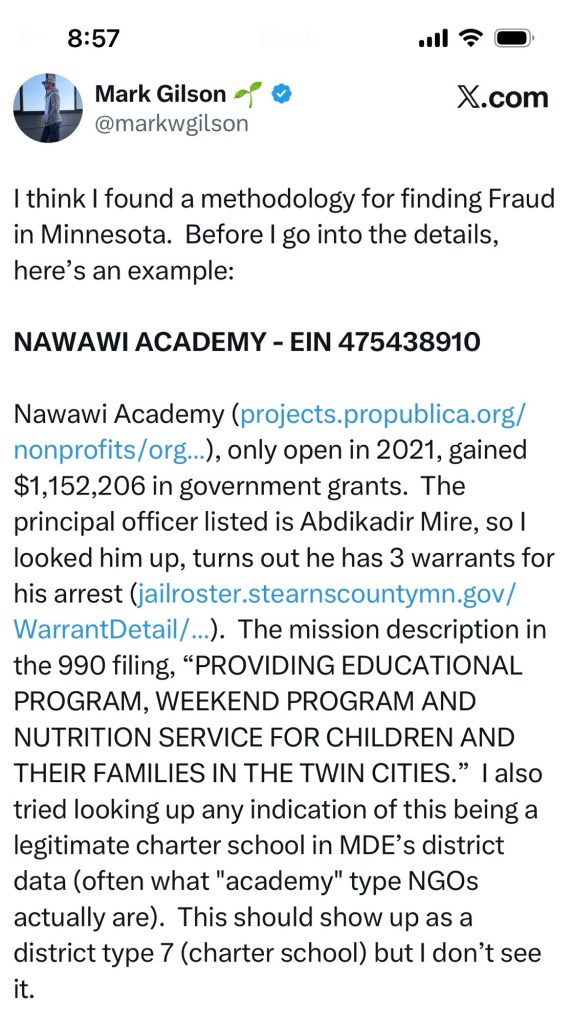

Mark Gilson (@markwgilson) is a local data nerd on X. Mostly, he has concentrated on getting out small details of ons-goings at school board meetings. He’ll post things from the agendas or video clips from the meetings, which busy parents don’t have time to attend,

The recent fraud explosion has opened up a new lane for his skills. In a post today, he describes how he filtered a search of the local non-profit public filings to locate ones with out-of-sync attributes.

Using this technique and his data skills, he found this doosey.

But instead of the methodology to sweep the public records, what about the mechanisms that attract people like Mark to take on this job? Indeed, it has to do with the recent stepping down of the Governor from his reelection campaign. It was an admission of a loss of confidence, perhaps even wrongdoing. But what would it take for an everyday citizen to get involved sooner? The hanky panky has been in play for about a decade. Investigative reporters are meant to take on this exposé-type work, but they didn’t. Could there have been other incentives to engage other members within the group to play the heretic? Or is a society doomed to fail magnificently before a complete shake-down and repordering occurs?

The concept of “orientation table” (plural: “orientation tables”) in economics refers to institutions—formal rules, informal norms, customs, laws, and social structures—that serve as cognitive and interpretive aids for individuals navigating an uncertain world of purposeful human action. These tables provide reference points or frameworks that help actors form expectations, anticipate others’ behaviors, coordinate plans, and attach subjective meanings to their situations, without rigidly determining outcomes.

Coined by Ludwig von Mises, the Austrian economist, the phrase draws from his praxeological framework in works like Human Action (1949), where he describes how individuals require guides for “orientation” in a chaotic reality lacking perfect causality or predictability. Mises emphasized that in an open-ended world, people rely on institutional “tables” to orient their actions, extending ideas from his earlier German writings on the role of social institutions in facilitating rational planning.

Virgil Storr and collaborators like Peter Boettke popularized and refined the English term “orientation tables” in post-2000 Austrian scholarship, particularly in papers such as “Post-Classical Political Economy: Polity, Society and Economy in Weber, Mises and Hayek” (2002). They portray institutions as non-deterministic “orientation tables” that embed economic action within social and political contexts, blending Mises’ methodological individualism with Max Weber’s interpretive sociology (Verstehen) and Friedrich Hayek’s spontaneous order.

For example, private property rights act as an orientation table by signaling legitimate control over resources, enabling entrepreneurs to plan without constant fear of expropriation. Market prices serve similarly, conveying dispersed knowledge to orient production and consumption decisions. Cultural norms, like trust in commercial dealings, provide additional tables in specific societies, explaining why markets function differently across contexts (e.g., bazaars vs. supermarkets).

In post-disaster recovery, community networks and property institutions orient survivors’ rebuilding efforts, fostering resilience. Absent robust tables—as in socialist systems lacking genuine prices—miscoordination and inefficiency arise.

Ultimately, by naming the orientation table under analysis, an observer can proceed with an aligned perspective. Rather than human action being socially embedded, individual action can be simultaneously quantified by group. This brings an understanding of price to complete the circle of individual and institutional value.

So many shapes and sizes.

Josh Hendrickson has an interesting New Year’s Day post on Economic Forces today. He reviews the term cooperation costs as proposed by Earl Thompson in a 1982 paper: Underinvestment Traps and Potential Cooperation. Hendrickson uses Thompson’s framework to discuss a breakdown or perceived breakdown in optimal investment in three scenarios. Each one offers a unique combination of the collective and private forces at work in the creation, penalty or use of a public good.

Let’s fit the first story about a mine, a port, and a road into the context I propose here at Home Economics. Instead of considering the whole landscape within a single system, break the system into groups, each with a mainspring to action. The mine is a profit-oriented venture. Its existence depends on the collection of actors that make up its workforce and investors, all of whom share an interest in extracting a private gain from their involvement. The group of people involved in the port’s operations is in a similar situation. The road is different. It is an infrastructure open to all nearby residents as well as those travelling for commercial needs. Roads are most often paid for by the larger group, as it is beneficial to most that their use remains open, even to the lowest payees. Even though members of GrMine and GrPort are also members of GrRoad, it is safe to assume the last group is significantly larger than either of the first two.

Earl Thompson’s model posits that the potential cooperation cost is the expense borne by investors in the mine and the port, along with the state, of communicating and bartering to secure the construction of the road. This happens at a fixed point in time, and once it is done, there are no more cooperation costs. Hence, the thought that those who come later free ride on the use of the road.

I propose to look at each group separately. Amongst the members of each group, there are shared social concerns. The ability to get to work on a good road may be one amenity of value. Yet the benefit of the new road for the mine workers may be a different value than the port workers, again depending on distances or substitutes that each set has access to. The municipality ( county/state or government structure of choice) is composed of a population that also should perceive a benefit from the road. However, this could be, on a per-person basis, of much lower value.

One of the three groups could be comprised of a population that is willing to pay for the entire road, as it is that valuable to them. If the mine is so remote, and the port area already has suitable transportation infrastructure in place, then in order to get employees out to the mine and product in from the mine, the mine might find it suitable to bear most of the expense. Or there could be some suitable combination. But the calculation involves each individual who must act for the enterprise to succeed.

There is also the possibility that the overarching group creates additional costs as members resist the new road due to costs not borne by either the mine group or the port group. If the road goes through a residential neighborhood, then the projected traffic noise has a negative impact on the residents, lowering their property values. In this communication stage of the project, their resistance to cooperation could be seen in city council meetings as voices of objection. Thompson’s model does not allow for outside resistance. Sorting by groups and their interests clarifies how costs are borne and hence who may sabotage cooperation.

There are all sorts of combinations of coordination costs between these three groups that could make it more worthwhile for one or the other to front the bill. We see developers putting in roads to provide access to a new development. We see municipalities investing in infrastructure to attract businesses. All of these choices are dependent on the particular situation and point in time. To say that those who come later take advantage of the cooperation costs of those who come before isn’t accurate, as the system is dynamic. They may not have paid for the cost, but they were not a part of any of the benefits of the original decision-making either.

The other factor facilitated by the sorting into groups is the time factor. The set-up time to open a mine is bound to be different than to complete a road. And what type of road are we talking: dirt, gravel, or asphalt? The reality is that these projects live over varying time spans. This factors into the decision to cooperate. Cooperation costs are not a single fixed cost, but a time-indexed stream of costs and benefits, discounted differently by each group.

The structural issue, for the purpose of analysis, is that the individual actors, reacting to their own concerns, reveal shared concerns with members of their group. The degree of this value plays into the cooperation costs of settling with outside parties on their shared interests. Thompson’s cooperation costs assume a fixed set of beneficiaries; once group membership, veto players, and time-path asymmetries are introduced, the free-rider interpretation no longer holds.

This site advances a structural theory of economic organization in which societies are understood as collections of bounded groups that govern shared resources internally while competing externally through privately capturable returns. The central claim is that economic order emerges from a sorting mechanism: individuals and activities are continually reallocated between cooperative group settings and market-like domains based on the relative performance of group-public assets versus private opportunities.

Within this framework, groups are defined not merely by identity or culture, but by rule-governed access to non-divisible or imperfectly divisible assets. Such assets—landed estates, commons, institutional authority, epistemic legitimacy—function as group-public goods: they are accessible to members, governed by internal norms, and resistant to direct pricing. Participation confers benefits that are distributed through social rules rather than markets, creating a publicness that is endogenous to group membership rather than universal.

Outside these groups, individuals engage in domains characterized by alienable, liquid, and privately capturable returns. These domains—markets, trade, professional careers, or platforms—permit competition unconstrained by group obligations and reward individual optimization. The boundary between group and market is therefore not fixed; it is continuously reshaped by changes in relative returns, enforcement capacity, and legitimacy.

The theory’s explanatory power lies in showing how publicness and competition are not opposites, but complementary outcomes of the same sorting process. Internally, groups suppress price signals and individual appropriation in order to stabilize shared assets and reduce coordination costs, consistent with Ostrom’s findings on common-pool resource governance. Externally, groups compete for members, status, and influence through performance, innovation, and access to higher-return opportunities, aligning with North’s account of institutional evolution driven by differential returns and path dependence.

This mechanism also integrates Mises’s praxeological insight that all outcomes originate in individual action. Individuals are not assumed to act altruistically or selfishly in the abstract; rather, they respond to institutionally structured opportunity sets. Actions that appear cooperative within the group—maintenance of shared assets, adherence to norms, acceptance of unequal internal distribution—are rational given the group-public payoff structure. Conversely, actions that appear self-interested outside the group reflect the higher marginal returns and certainty of private capture. The theory thus avoids moralizing distinctions between cooperation and self-interest, treating them as context-dependent expressions of action under differing institutional constraints.

Historically, the theory explains periods of social transition as moments when private returns in external domains outpace the productive or legitimating capacity of group-public assets. Under such conditions, groups become custodial rather than generative: obligations persist while returns stagnate. Individuals increasingly sort into private domains, weakening internal enforcement and prompting pre-commitment maneuvering, ideological rationalization, or reform efforts. This dynamic aligns with classical coordination problems such as Rousseau’s Stag Hunt, while extending them beyond static games into historically embedded institutional change.

By framing economic structure as an evolving ecology of groups and markets linked through a sorting mechanism, this theory bridges literature on institutions, collective action, and market pricing. It accounts for why public goods are often effectively governed at intermediate group scales, why markets excel at allocating marginal resources across groups, and why systemic change is typically gradual, conflictual, and legitimacy-lagged rather than abrupt or purely efficiency-driven.

In sum, the proposed framework offers a unified explanation for how societies organize cooperation internally while sustaining competition externally, and how shifts in resource productivity drive the continual reconfiguration of social commitments and economic structures.

Imagine a small group of hunters living at the edge of a forest. Together, they can hunt a stag. A stag is large: it feeds everyone for days. But it can only be taken if all hunters cooperate, hold their positions, and act in coordination. The stag, once caught, is a group-public asset: no one hunter can claim it alone, and everyone benefits.

Individually, however, each hunter can hunt a hare. A hare is small, but it can be caught alone, quickly, and with certainty. The hare is a private asset: the hunter who catches it keeps it.

At first, cooperation dominates. The group trusts itself, norms are strong, and everyone expects the others to stay. Hunting the stag makes sense.

But conditions begin to change. Perhaps the forest becomes less predictable. Perhaps hunger becomes more acute. Or perhaps some hunters discover they are particularly good at catching hares. The private return to individual action rises, while the reliability of collective action weakens.

Now the calculation shifts. Any single hunter who abandons the stag hunt early can secure a hare for himself. If even one hunter defects, the stag escapes and the group gets nothing. As more hunters privately consider this possibility, the group-public asset becomes fragile. Trust erodes not because cooperation is irrational, but because its success depends on others remaining committed.

Eventually, everyone hunts hares. The group survives, but on less than it could have had. The stag hunt fails not because hunters become selfish in character, but because the balance between public and private returns has shifted.

Rousseau introduced the Stag Hunt in 1755, in Discourse on Inequality, as a way to illustrate how early cooperation collapses when private, individually secure options undercut fragile collective commitments. The Stag Hunt shows how cooperative systems fail not through greed, but through the gradual rise of privately secure alternatives that undercut shared commitment.

My experience is that mostly hunters group up. Partly because they share a similar interest. Partly for the camaraderie. But also because they share the work of baiting, setting up, tracking, and processing.

In this ten-minute video, economic professor Ashley Hodgson lays out how a shift at the foundational base of a field of knowledge occurs and builds on new building blocks.

Ashley Hodgson’s New Enlightenment argues that modern societies are governed less by conscious choice than by incentive-driven systems that shape beliefs, behavior, and outcomes at scale. Drawing on behavioral economics and systems thinking, she challenges Enlightenment assumptions about rational individuals, neutral markets, and linear progress (especially GDP-centric thinking). Her central claim is that humans now function within a kind of social superorganism, where misinformation, institutional incentives, and feedback loops distort what people perceive as rational or true. A new enlightenment, she argues, requires updating our models of rationality, knowledge, and governance to reflect these systemic dynamics rather than relying on outdated economic myths.

Hodgson offers a compelling critique of Enlightenment assumptions and a sophisticated account of systemic failure, but her ‘New Enlightenment’ functions more as a diagnostic framework than as a theory of institutional emergence or system dynamics.

Keep an eye out for the dragon

According to research from the National Association of Realtors:

If you’ve been taking the classics for granted, if you’ve been focusing on science, you are denying yourself insights into solutions.

—A submissive spirit might be patient, a strong understanding would supply resolution, but here was something more; here was that elasticity of mind, that disposition to be comforted, that power of turning readily from evil to good, and of finding employment which carried her out of herself, which was from Nature alone. It was the choicest gift of Heaven; and Anne viewed her friend as one of those instances in which, by a merciful appointment, it seems designed to counterbalance almost every other want.

J Austen reviews the intricacies of social decision making under constraints both natural and real.

A memory from years gone by, but the message is enduring.

May the baby in the manager bring grace into your lives and protect you from harm.

Personal size and mental sorrow have certainly no necessary proportions. A large bulky figure has as good a right to be in deep affliction, as the most graceful set of limbs in the world. But, fair or not fair, there are unbecoming conjunctions, which reason will patronize in vain,-which taste cannot tolerate, —which ridicule will seize.

A ‘bulky figure’…c’est amusant.

By “orientation-by-institution,” I refer to the way institutional arrangements function as shared interpretive frameworks that orient expectations and render individual plans mutually intelligible under conditions of uncertainty.

Chat has a story.

They were halfway through lunch—salads mostly untouched, bread already gone—when someone noticed it.

“Did you see her hair last week?” one of them said, lowering her voice even though the person in question wasn’t there. “It actually looked really good.”

“Yeah,” another replied, “but doesn’t she get it cut at Little Snips? Why does she even go over to that side of town?”

That set it off.

“Well, the cut is good,” someone said, “but it’s not like it’s magic. You can get a decent cut anywhere.”

Another leaned back and laughed. “Decent? Please. She pays way too much. That shwanky salon—what is it now, Maison Something? It’s nice, sure, but the cut is the same cut whether you pay forty dollars or two hundred.”They all laughed, because it was true and because saying it felt good.

Then someone else chimed in, quieter but smiling. “Honestly, my sister-in-law cuts my hair in her basement. Folding chair, mirror from Target. I probably overpay her too, but at least I know where the money’s going.”

That changed the tone just a little.

“So really,” one said slowly, “we’re all paying for different things.”

“Exactly,” another added. “Not just the cut.”They started listing it out without meaning to: paying for polish, for status, for supporting family, for convenience, for being seen in the right place, for not being seen at all. Same service, different prices—because each price bought entry into a different social arrangement.

By the time the check came, no one was talking about hair anymore. They were talking about neighborhoods, schools, reputations, obligations—about how money quietly props up the social worlds they move through every day.

And no one asked again why their friend went to Little Snips. They already knew

I’m a fan of Daniel Craig, so I may be biased in this whole-hearted recommendation of the new Knives Out movie. Viewers will come away satisfied with the intrigue, the cast of characters, and the denouement of solving the crime. It’s all there. But there’s more.

In a surprising twist, this new release delves deeper. Writer Rian Johnson uses the exploration of faith as a central theme in this third incarnation of Knives Out. Somehow in this otherwise commercial entertainment vehicle, he depicts journeys of faith without condensation of suspended disbelief or mockery.

Is this the beginning of a new tolerance for ancient traditions? There was a magic in it.

Thus there are no irreconcilable conflicts between selfishness and altruism, between economics and ethics, between the concerns of the individual and those of society. Utilitarian philosophy and its finest product, economics, reduced these apparent antagonisms to the opposition of short-run and long-run interests. Society could not have come into existence or been preserved without a harmony of the rightly understood interests of all its members.

There is only one way of dealing with all problems of social organization and the conduct of the members of society, viz., the method applied by praxeology and economies. No other method can contribute anything to the elucidation of these matters.

If people want effects muted they draw out terribly long time tables, muting any situational success or failure. If people want to control the narrative they clip the timetable to the period of interest.

Time matters for any proper analysis or policy considerations. In real estate, the timeframes are almost always too short.

At home-economic we think of work as an activity within an analytical structure which proposes that human action is propelled by two forces. The work often associated with volunteerism percolates along, driven by the desire to help, to impact more than oneself.

This is from a lovely essay by Russ Roberts

Aristotle has a different explanation and it is quite beautiful. He says that unlike a creditor (who only cares about the recipient because he wants to be repaid), “benefactors love and are fond of those they have treated well, even though they are neither useful to them now nor likely to become so later on.” He then says something a little shocking and quite extraordinary. The bracketed phrase is Leon’s:

“The same thing also happens with craftsmen; for every craftsman loves his own work more than he might be loved by that work were it to become alive. This is especially true, perhaps, with poets, for they love exceedingly their own poems, loving them as children. This is in fact also the case with the benefactor, for the beneficiary is the work of the benefactor; thus, the benefactor is fond of him more than “the work” [that is, the beneficiary] is of its maker.”

National vacancy rates in the third quarter 2025 were 7.1 percent for rental housing and 1.2 percent for homeowner housing. The rental vacancy rate was not statistically different from the rate in the third quarter 2024 (6.9 percent) and not statistically different from the rate in the second quarter 2025 (7.0 percent).

National vacancy rates in the third quarter 2025 were 7.1 percent for rental housing and 1.2 percent for homeowner housing. The rental vacancy rate was not statistically different from the rate in the third quarter 2024 (6.9 percent) and not statistically different from the rate in the second quarter 2025 (7.0 percent).

The homeowner vacancy rate of 1.2 percent was higher than the rate in the third quarter 2024 (1.0 percent) and higher than the rate in the second quarter 2025 (1.1 percent).

The homeownership rate of 65.3 percent was not statistically different from the rate in the third quarter 2024 (65.6 percent) and not statistically different than the rate in the second quarter 2025 (65.0 percent).

Full article here.

Sir Walter must face financial circumstance and lease out his country manor home. The go-between, Shepard, spouts off all the appealing characteristics of his potential tenant.

And who is Admiral Croft?” was Sir Walter’s cold suspicious inquiry.

Mr. Shepherd answered for his being of a gentleman’s family, and mentioned a place; and Anne, after the little pause which followed, added—

” He is rear admiral of the white. He was in the Trafalgar action, and has been in the bast Indies since ; he has been stationed there, I believe, several years.

One must be careful using the family word in real estate, today. Best to think of other descriptors. But not personal features as such:

Mr. Shepherd hastened to assure him, that Admiral Croft was a very hale, hearty, well-looking man, a little weather beaten to be sure, but not much; and quite the gentleman to he sure in all is notions and behaviour.

Outward characteristics are not to be asked or recorded on a rental application. But the terms of the unit can be recorded.

not likely to make the smallest difficulty about terms; only wanted a comfortable home, and to get into it as soon as possible; knew he must pay for his convenience;-knew what rent a ready-furnished house of that consequence might fetch; should not have been surprised if Sir Walter had asked more;-had inquired about the manor;

Oh- and there’s this.

—would be glad of the deputation, certainly, but made no great point of it;— said he sometimes took out a gun, but never killed ;—quite the gentleman.

And theres lots to say about the family. (Also a no-no today)

Mr. Shepherd was eloquent on the subject; pointing out all the circumstances of the admiral’s family, which made him peculiarly desirable as a tenant.

He was a married man, and without children; the very state to be wished for. A house was never taken good care of, Mr. Shepherd observed, without a lady: he did not know, whether furniture might not be in danger of suffering as much where there was no lady, as where there were many children. A lady, without a family, was the very best preserver of furniture in the world. He had seen Mrs. Croft, too;

All these rich social indicators are removed when renters seek homes in today’s market.

Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, since as members of one body you were called to peace.

And be thankful.

Let the message of Christ dwell among you richly as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom through psalms, hymns, and songs from the Spirit, singing to God with gratitude in your hearts.

And whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through Him.

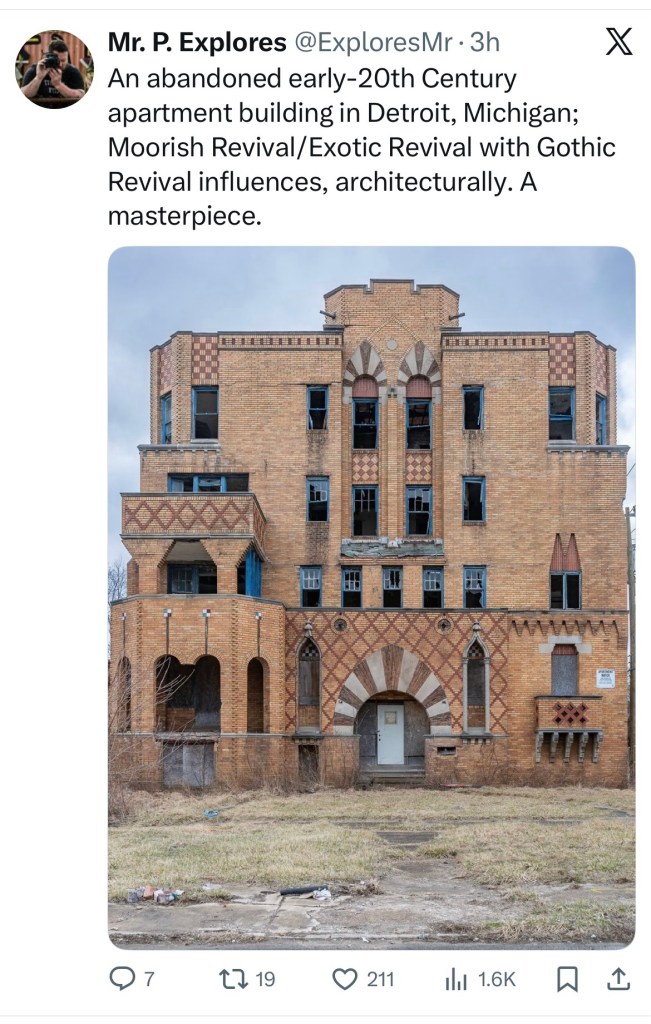

Standards can change over time.

Standards can vary between cities.

Standards may vary based on taste.

Ultimately, it is the local community that determines which options are the most suitable and which are less desirable. Which have fallen so out of favor that the structures are abandoned completely. And which ones promise a reward for rehabbing.

Real estate is local. National figures provide sparse details.

It’s the holiday season, and this film offers family-friendly entertainment that appeals to a crowd . There’s action. There’s comedy. It’s pro-family. So, once everyone has had their fill of holiday food and just wants to lie around on the couch, keep this film or its sequel, Family Plan 2, in mind.

When should a community gather up its resources and provide a service to all members? And when should individuals be turned out into the world to navigate on their own dime? These debates cross all levels of government.

Some provisions are accepted as a government thing, like piped water or sewer. Even basic universals like education attract conversation about private options. Roads are sometimes (although truly not very often) toll roads. Bridges are mostly a public venture, as are parks. What takes a good out of private production and places it in the receivership of a bureaucracy?

Fear usually. Police and firefighters are in place to ensure personal safety. The New Deal was to alleviate fears against a repeat of depression era outcomes. When society risks a loss that compels a human response, society steps forward with a safety net.

Mamdani, New York Cities new mayor, sold the people on a fear of escalating grocery prices and thus the need for a government run store. This seems different than when a small community rounds up a helicopter rescue for a mountain climber who ventured up a nearby peak alone and unprepared.

So who gets to pick what there is to fear? Not everyone does this well. Here’s Mises (from Theory and History)

They recommend some policies, reject others, and do not bother about the effects that must result from the adoption of their suggestions.

This neglect of the effects of policies, whether rejected or recommended, is absurd. For the moralists and the Christian proponents of anticapitalism do not concern themselves with the economic organization of society from sheer caprice. They seek reform of existing conditions because they want to bring about definite effects. What they call the injustice of capitalism is the alleged fact that it causes widespread poverty and destitution. They advocate reforms which, as they expect, will wipe out poverty and destitution. They are therefore, from the point of view of their own valuations and the ends they themselves are eager to attain, inconsistent in referring merely to something which they call the higher standard of justice and morality and ignoring the economic analysis of both capitalism and the anticapitalistic policies. Their terming capitalism unjust and anticapitalistic measures just is quite arbitrary since it has no relation to the effect of each of these sets of economic policies.

Taking over a grocery is sure to fail financially without ensuring any additional food security for those who need it. It’s a vanity project. Wouldn’t it be like telling the mountaineer that a government representative would need to participate in the planning and execution of his climb? Yet here, the little community bears a disproportionate cost for the climbers’ foolishness.

It seems that the risk to persons and the community happens to various degrees. Whether the risk triggers community involvement has to do with its extreme and the distance between the risky step and all the other steps in between.

I died for Beauty - but was scarce

Adjusted in the Tomb

When One who died for Truth, was lain

In an adjoining Room -

He questioned softly "Why I failed"?

"For Beauty", I replied -

"And I - for Truth - Themself are One -

We Brethren are", He said -

And so, as Kinsmen, met a Night —

We talked between the Rooms -

Until the Moss had reached our lips -

And covered up - Our names -

People speculate why young people have delayed home purchases. Only around 20% of home purchases fall in this category. A historic low. But is it that surprising? Look at the surge of foreclosures in ’07-’08 and ’09. Hundreds of thousands of people who were never meant to have financial struggles lost their homes.

Children ages 8-12, old enough to sense the stresses within their families, yet too young to analyze the impact of a national financial crisis, were bystanders to these unpleasant legal actions in the early 2000’s. These are today’s young home buyers. Uncertain of what a real estate purchase will do for them. The anxiety associated with foreclosures has often been portrayed in litterature.

In Death of a Salesman, the family’s fear of losing their home emerges gradually, revealed not through a dramatic announcement but through Linda’s quiet confession that they are barely keeping up with the mortgage. She tells Biff and Happy that Willy has been borrowing money just to make the house payments—a disclosure that reframes the entire domestic landscape. What had seemed like an ordinary family home is suddenly understood as something fragile, held together by secrecy and strain.

The looming threat of foreclosure exposes the play’s deepest emotional fractures. The mortgage becomes a symbol of Willy’s unraveling identity—his failure as a provider and his desperate clinging to the American Dream. Linda’s hushed explanations carry a mournful tenderness, showing how fear and loyalty tangle together under financial pressure. For Willy, the house is both sanctuary and burden, and the possibility of losing it turns that symbol of pride into a reminder of collapse. The family’s anxiety over the home’s instability reveals how economic pressure corrodes affection, pride, and hope, tightening around them until it shapes every gesture they make toward one another.

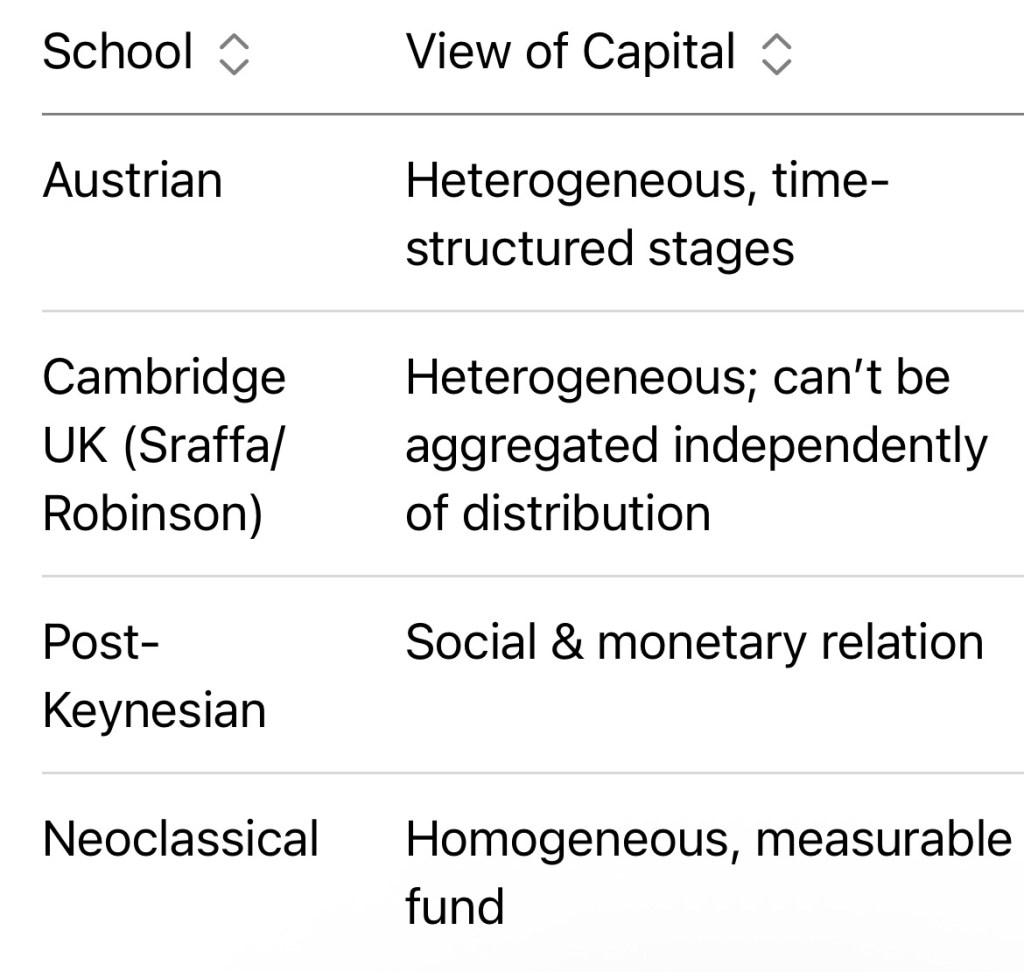

Capital theory is the branch of economics that studies the nature, role, measurement, and productivity of capital — the produced means of production (machines, factories, tools, infrastructure, software, etc.) that are used to produce goods and services.

It tries to answer fundamental questions like:

Capital theory has been one of the most controversial and technically difficult areas in economics, especially in the 20th century.

Capital theory is the attempt to understand one of the most important concepts in economics — capital — and it remains unresolved. The mainstream treats capital as a simple scalar quantity for modeling convenience, but the Cambridge controversies showed that this simplification has serious logical flaws once you dig into the details. The debate is largely dormant in mainstream teaching but still very much alive among economic methodologists and heterodox economists.

Landlord portrayal in Bleak House.

As it was still foggy and dark, and as the shop was blinded besides by the wall of Lincoln’s Inn, intercepting the light within a couple of yards, we should not have seen so much but for a lighted lantern that an old man in spectacles and a hairy cap was carrying about in the shop. Turning towards the door, he now caught sight of us. He was short, cadaverous, and withered; with his head sunk sideways between his shoulders, and the breath issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within. His throat, chin, and eyebrows, were so frosted with white hairs, and so gnarled with veins and puckered skin, that he looked, from his breast upward, like some old root in a fall of snow.

Life ain’t perfect. Neither are we.

The theory proposed here, at home economics, is that there’s a nature to how people act to improve their lives. For lack of better names, activities occur in spheres with public-facing tendancies or private ones. When people operate for the group, they give to improve for an affiliated public endeavor, whereas the private sphere engages privately held resources to grow and gain.

I think this framing helps to explain the suggested paradox described in this Free Press article about a Chicago Trump supporter coming to the aid of Venezuelan migrants.

Aleah Arundale voted for Donald Trump, supports his decision to close the border, and may as well have introduced herself by singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” when we met at her front door in Chicago last month. She was wearing a white sweatshirt with “USA” plastered on the front, a sequined American flag skirt, heart-shaped red glasses, and bedazzled red and white sneakers.

She also has spent the last three years helping Venezuelan immigrants. It began when buses from Texas started dropping off people at a street corner near where Arundale’s daughter went to dance class, as part of Governor Greg Abbott’s expulsion of thousands of immigrants to sanctuary cities across the country.

When Aleah makes decisions as a Chicago resident, her choices are weighed out within that context. Her group interests lie primarily on her block or down the street. She can be pro-Trump and anti-everyone-else-outside-our-boundaries. This keeps her public dollars and work weighted to the local food shelf, her elderly parents’ care, or a literacy program at the public library. Any outside force taking resources away from these microtransactions is a competitor.

But then the immigrants are dropped off by the busloads, on the corner where kids get picked up by the school bus. They’ve switched groups. No longer are they an impersonal one of many in a faraway place; they’ve breached the group. They now rate as the most in need within this new framing. And thus, the mechanisms that drive the force for the good of the group are energized. Aleah gives the plight of the Venezuelians in some rank or fashion amongst her other commitments.

There are two things to see here. First– the framing of the group and thus its acknowledgement. Second, the lever for activating time, energy, and resources differs from the private sphere. Yet this all transpires through a juggle of tradeoffs trapped in a world of constraints.

The comparison of home prices to buyers’ incomes is a popular measure for assessing the health of the real estate market. Presently, that multiple seems high, and people are using it to cry, crisis! But is this true?

Amy Nixon posts on Twitter (now known as X):

All of economics is supply and demand.

The median household to median income argument makes sense only in an economy where we have built enough housing units per capita, and every housing unit is being allocated as a family shelter unit because it serves no other economic utility

The model breaks down when you have wealthy families buying 3-4 spare vacation homes. And mom and pop landlords hanging onto starter homes when they upsize. And institutions buying millions of single family homes. And single people living alone in two units instead of coupling to buy one unit. And foreign citizens buying homes. And people buying and using 2 million single family homes as hotels (Airbnbs)

So long as single family residential housing is viewed as and can be used as an investment or luxury item beyond owner-occupied shelter and we don’t build enough homes to offset all those other uses, the ratio pictured in the infographic below can (and will) go even higher over time

It’s not 1985. And it’s never going to be 1985 again.

What Amy says is that there is a mix of home-ownership types. If you are analyzing Lake Country, with many second homes, there will be a different price-to-income figure than if you consider a first-tier suburb built almost exclusively of starter homes. I like to call them platters. It’s the local eco-systems of properties that have interesting numbers. Averaging just smudges out all the details.

I’ll also note the shift in demographic mix. The number of first-time buyers is at an all-time low. From NAR:

WASHINGTON (November 4, 2025) – The share of first-time home buyers dropped to a record low of 21%, while the typical age of first-time buyers climbed to an all-time high of 40 years, according to the National Association of REALTORS®’ 2025 Profile of Home Buyers and Sellers. This annual survey of recent home buyers and sellers covers transactions between July 2024 and June 2025 and offers industry professionals, consumers, and policymakers detailed insights into homebuying and selling behavior.

Repeat buyers enter the market with equity. They do not need to take on as much debt relative to their income as first-time buyers do. Yet the sales price is the measure from which payment is extrapolated, not the actual payment. As a market rises, so does the equity, pushing this fictitious measure of debt load out of whack with reality.

As the holiday long weekend comes to a close, one can be assured that not all celebrations went off as planned. Family get-togethers can be precarious. The long histories, the past grievances, the careless gestures or phrases can all contribute to a combustible mix. Sometimes tensions bubble up simply because people’s lives are busy, or a shift in circumstance generates unexpected demands. And then sometimes there is a troublemaker in the crowd.

Unhappy people want to drag every one around them into the muck. And a common strategy is to fabricate irrelevant procedures, standards, or hoops to impose on others, then criticize them for not meeting those arbitrary demands. This tactic shifts focus from substantive issues to compliance with a contrived process. It’s like building up a whole hoopla by setting up hurdles.

Some of these tactics are well known and used through many facets of life. Take moving the goal posts. As soon as someone deserves congratulations, some new expectation is placed upon them diminishing their accomplishment. There’s gatekeeping. A self appointed czar controls access to a group, idea or status. Bureaucratic tyranny causes delays and the classic red herring gets everyone off the topic and into some other pernicious yet irrelevant topic.

To sum it all up in a definition:

Hoopla Hurdles (n): The tactic of fabricating irrelevant procedures, rules, or requirements to avoid addressing real issues, maintain control, and generate conflict. Named for the endless, pointless hoops troublemakers make others jump through.

If you are curious as to whether the obstacles at hand are legit or Hoopla Hurdles, consider these diagnostic questions:

1. Was this rule just invented?

2. Does it solve the actual problem?

3. Would a reasonable person demand this?

4. Does it create more conflict than it resolves?

If 3+ yes → Hoopla Hurdles detected!

What you can do to placate the beast in the damaged person who would prefer to fight rather than befriend.

Response: Return to the original issue

“Let’s focus on whether the policy works, not the paperwork.”

Response: Highlight the irrationality

“Why does a 2-sentence petition require a PhD?”

Response: Refuse to play

“I’ll discuss the idea, not your 17 rules.”

Response: Apply their logic back

“If I make you read 50 articles first, will you?”

Response: Deflate with ridicule

“Should I also sacrifice a goat under a full moon?”

Pro Tip: Combine tactics for maximum effect! 🏆

Beauty can be high maintenance.

The phrase “the mainspring of the story” is a metaphorical expression that refers to the central driving force or primary motivation that propels the narrative forward. Just as a mainspring in a mechanical watch provides the energy to keep it running, the mainspring of a story is the core element that gives it momentum, purpose, and cohesion.

In life, there are often several intermingled motivations pulsing through the engine for action. But usually there is a mainspring– one impulse pulling in the lead. You would skip going to the grocery except for the turkey for Thanksgiving. And since you are there, another couple of dozen food items also end up on the metal grid at the bottom of the cart. The supermarkets have gotten wise to such things and tempt shoppers into their aisles by advertising the big bird at 77 cents a pound.

Sometimes the mainspring is a different type of impulse. Instead of competing for the lowest price, this mainspring is about giving to the most significant number. A mainspring may drive a young guy to work as a manager at a supersized grocery for a quarter century. But then things change. And the same individual, with the same set of skills, might be driven to help others by working as the manager of a food shelf.

Sometimes people hide their mainspring. They don’t want to be judged by the we they find themselves amongst. Sometimes this subversion is enacted through substitution —no, I’m not buying it for prestige; I’m buying it to make my wife happy. Ok. Right.

Some mainsprings are treacherous. Fear, for instance. Fear as a mainspring can drive all sorts of damaging or wasteful actions. Fear of running out of food means you bring home too much, and it spoils. Fear of buying too much means you can’t quite complete your menu and are always falling short of a satisfying meal. And of course, fear instigated by others is ultimately responsible for some type of corruption in the system.

When trying to put a model around our messy world, first find the locus of action. Who exactly is the source of the analysis? Then find their mainspring, whether hidden or out in plain sight for all to see. Otherwise, you are just another jammerer floating all sorts of ‘we’s’ that bob on the waves of idle conversation with no direction at all.

Excited for the morrow.

“What can you do to promote world peace? Go home and love your family.” – Mother Teresa

No one in the western world really questions whether water provision is best suited to the public or private spheres. Being hooked up to city water and sewer is unanimously considered a good thing. Was it always that way? Well- no. Londoners purchased water from private suppliers through the end of the nineteenth century.

John Broich gives an excellent history of how the desire for water provision shaped London.

His account tells how secondary cities in the British Isles adopted a municipal water system decades before the great capital on the Thames. In fact, the continued delays in accomplishing this civic feat help exemplify the many facets of interests and the levers in play. There are issues of pollution and health concerns, there are networks of private providers, and the wealthy who buy their way to what they want. There is petty jealousy and the pride of belonging to an international city. And most astonishing, there is no government structure to handle such infrastructure outside of the walls of ancient London.

For provincial water reformers, the principles on which the administration of water was based-as well as the engineering principles on which water provision was based-were meant to make their cities more modern in the sense expressed by Avery, the Birmingham councilor.

“When water is under the control of private companies, the chief desire of the directors is to obtain good dividends,” said a Bradford town councilor in 1852. “When the Town Council possesses the works,” he continued, “their chief object is to make the works instrumental to the promotion of cleanliness, the health, and the comfort of all classes of citizens.”57

Water administration by a directly representative body was to provide an obvious contrast to the commercial companies that made independent decisions about water quality, abundance, and price based on the profit motive.

It is an excellent story depicting the nature of what is public and what is private. For a literary companion piece, consider reading Dickens’s Bleak House.

Maybe in some parts of the country housing is so tight that there’s a return of the boarding house.

Or are have they been regulated out of the landscape?

When you read this post

Do you think affordability crisis? Or—consumer choice to play it safe, not take on the obligations and commitments of a house, and choose to rent?

There’s truth in this phrase.

There is no blob of “government” money, or “policy” that can make something affordable for one without making something else less affordable for another.

So if tenants get immediate relief from a rent freeze, where does that money come from?

Those outside the business may think that this will trigger a direct transfer from a wealthy landowner. Structurally this is an impractical notion. Even for those who have equity, it is just that: wealth tied up in the value of the property. It is not cash that can circulate and pay bills.

But in most all cases, the funds that come in from rent are pegged to go out to another obligation. This might be property taxes which are known to increase every year. This might be to a bank that financed the purchase of the property. And the insurance company which provides property isurance as required. This might be to a utility company. Each of these obligations have recourse for non-payment which ultimately leads to their making first claims on the income.

The funds which subsidize the rent freeze are most likely to come from monies intended for repairs and maintenance of the property. These vary from tasks that are good to do but not urgent, to things that if defrayed cause additional costs, to things that need immediate attention like a leaky pipe or a furnace outage. To give an idea of the number of routine items involved in the care of real estate, consider this post.

Over time, two things tend to occur. First, the new landlords with all their positive energy and desires to get ahead can’t maintain a financial foothold and leave. Other longer term owners prioritizes the most important fixes but let the cosemetic upgrades go. Over time more and more of the longer term components age, yards get overgrown, appliances become run down. The housing stock deteriorates.

The neighborhood at large is depreciated by blight, taking a little chunk of equity from every property owner nearby.

Is so cool.

More please.

The biggest losers of rent control are the young, the mobile, the ambitious, immigrants, and people without a lot of cash. If you want to move from Fresno to take a job in San Francisco and move up, and you don’t have millions lying around to buy, you need rentals. Rent control means they are not available. Income inequality, opportunity, equity, all get worse.

In this paragraph, John Cochrane begins to draw lines around groups of people who will lose out under a rent-control, a policy that favors those who have established leases with landlords.

The reader can quickly imagine a young person being squeezed out of houisng by the combination of entry-level pay and bulked-up rent. The surcharge is necessary to balance out the rent-controled units. That’s the persona that comes to mind and it is the one the author intends to convey. But wait. What about the just-out-of-school coders and engineers that are swooped up by the tech companies?

These kids are paid a lot money. They are can choose where to live without much concern as, most often, they have no other attachments. They all live together in some big tech hub, often times leaving their childhood communties behind. They no longer have other points of reference like a brother who took up plumbing, or grandparents on fixed income. Not only do the have the cash flow to spend they are not being reminded that others do not.

One descriptor is not enough to form a group. To say the population of Minnesota has remained constant is light on details. Susan Bower, the state demographer, explains some of the demographic breaks down in Eden Prairie, a SW suburb of the Twin Cities. At the presentation she notes the the state loses 5,000-10,000 people a year but it is made up through international immigration. In other words, the people who leave have no concerns regarding rent control are replaced by a group who are disadvantaged by rent control.

To be efficient, matching people in consideration of their stage in life with their housing needs is best. Policies which keep people in place or discourages them from moving up, moving closer to employment, moving to a stronger school district, moving closer to support systems and so on are detrimental.

Check out all the colorful parcels of property owned by public entities.

The Grumpy Economist has another great post, this time about rent control. For those of us in real estate, it’s an irritating topic. The errors in the use of price controls are numerous. Using John Cochrane’s article as a road map might be interesting to illustrate this point. Let’s start with this paragraph.

Sure, “sharply rising rents and utility bills wreak havoc on family budgets,” if the families don’t follow the screaming market signal to move. (Which is not painless, for sure. Incentives never are.) But the money comes from somewhere. Rent controls and energy price caps wreak havoc on landlord end electric utility budgets. The money must come from somewhere.

The claim is that rents are rising sharply. The reader pictures a Scrooge-like figure pounding on the door of a cowering family of four, announcing a ‘sharp’ rent increase (extra dollar symbols for emphasis), while behind this embodiment of the typical landlord stands an eviction notice ready to be served. I’d love to see numbers to this effect. I challenge that the ‘sharp’ rent increases are occurring at lease renewals.

Large corporate landlords might have a set policy of annual increases, but they account for only 3-4% of proprietors. Landlords must juggle the cost-benefit of increasing rent. As 80% own and manage the units, they calculate the costs, time, and uncertainty of a new tenant. This is weighed against a 3% increase on $1,100 or $33/mo in additional income. Needless to say, many landlords will forego a rent increase to keep a good tenant.

These subtleties are lost in real estate analysis, where all the numbers are averaged as if there were one typical renter, one typical landlord, and one typical property. This couldn’t be further from the truth. There are whole economies of renter groups. There are students who will have negative income before they join the workforce; there are singles with high-fluting jobs and no other responsibilities; there are single parents; there are couples with kids in a city just for a bit; there are elderly on fixed income with low mobility; there are recently divorcees looking for a glamorous downtown lifestyle.

Are all these groups to receive the same treatment? The same concern for their monthly budgets?Rent controls are initiated at the city level. Every group of renters would receive the benefit of a market-restrained obligation. Is that the intention?

Landlords are also assumed to be a certain type. The persona has tremendous equity in their property, no debt, and other cash they are stashing like squirrels do with acorns in the fall. And certainly some landlords fit this description. But more likely than not, the landlord has a mortgage and obligations against their time. The new entrants to the field, those trying to get ahead by getting a foothold in real estate, are undoubtedly the ones who need to make the cash flow.

When property taxes, utilities, or the cost of hiring labor rise, a landlord has no way to respond until a lease comes up for renewal. Rent control tightens this squeeze, leaving property owners caught between increasing public demands funded through taxation and their limited ability to recover those costs through rent. The first to be pushed out are often the newcomers—the small, aspiring owners who bring fresh energy and ambition to the market, but lack the cushion to absorb sustained losses.

Lesson number one. Averaging is a mistake. Assuming there is only one type of each actor in this economic trade of money for lodging makes for an impossible conversation.

I find an extra element of enthusiasm in Victoria Wyeth’s examinations of her famous grandfather’s paintings. She has many more posts on her FB page (which I could not figure out how to embed!)

One of my favorite Andrew Wyeth paintings has a post of its own.

I’m quite enjoying Allison Schrager’s accounts of how people navigate risk in their lives. The book is full of stories about poker players and surfers, as well as bankers and bond traders.

Although the framework follows the model of an individual making a decision, in the background there are many communal references. This passage is about the paparazzi partnerships.

Since the best shots come down to being in the right place at the right time, photogs often form teams or alliances to share tips and sometimes royalties to increase the odds or payoffs they’ll be in that place. In 2003, Baez founded a group called PACO, “like the jeans,” combining the words “paparazzi” and “company.”

PACO consisted of ten experienced photographers. They traded tips on where certain celebrities hung out and when. So if Baez spotted a celebrity eating lunch at a trendy restaurant, he would alert the other PACO members. He says, beaming with pride, “Back in the day when we’d show up, the other guys would say, ‘Oh no, here comes PACO, because we were the best.”

Family ties show up in several of the vignettes. Somehow the prospects of his first love trump a degree from Stanford. When talking about the business executive Arnold Donald, she recounts.

It was a way to get both worlds: the liberal arts experience he wanted and the Stanford engineering degree.