Opening rifle season

Searching for value

I would argue no, for several key reasons.

First, a medical procedure’s success depends heavily on patient participation. The outcome hinges on whether patients follow their physician’s instructions, avoid harmful foods or activities, commit to their rehabilitation, and make necessary sacrifices for optimal recovery. A car, by contrast, operates on a predictable maintenance schedule—oil changes every 7,000 miles, new tires at 50,000 miles—and doesn’t require active participation each time you get behind the wheel to function properly.

Second, evaluating medical outcomes is inherently subjective, shaped by individual expectations and varying standards of success. A tangible good like a car, however, has objective, measurable qualities that remain consistent regardless of who’s assessing it or observing it.

Finally, medical procedures carry inherent risk. Unlike most purchases, where you start at a baseline and gain utility, healthcare interventions don’t guarantee positive outcomes. A procedure can result in complications requiring additional interventions, meaning you could begin at zero and end up worse off. There’s always the possibility of a negative outcome, which fundamentally distinguishes healthcare from consumer goods.

For these reasons, healthcare tends to be heavily influenced by social groups. Peer pressure encourages people to take care of themselves. Role models who demonstrate how to go the extra mile can influence and encourage patients to do the same. The extent of care may be directed in part by group expectations. But, the most significant risk with this over a car or other tangible goods, is that lack of care or poor care can cause the patient to go backwards and incur even more costs both to the body and the pocketbook.

It’s really good! Watch it.

Roles are always changing.

But it required more than an annual tour to administer and exert royal power throughout Scotland. The size and geography of the kingdom required the representation of royal authority at both regional and local levels. This was carried out by two tiers of royal officials.

MORMAERS

Mormaers were powerful territorial magnates and their extensive provinces were the primary level of royal administration in eleventh-century Scotland. Mớrmaer means ‘great steward’ and this Gaelic title is first recorded in 918, although its origins are unclear. The absence of mormaers in Ireland indicates that this office was not introduced with the migration of the Dál Riata or from Ireland at a later date. Instead, the predominantly north-eastern distribution of the Scottish provinces recorded as having mormaers suggests that this office had Pictish origins. It may have originated in the provincial kingships that lost their royal status as the kingship of the Picts became increasingly centralised.

However, the disappearance of the earlier Pictish provinces and their names suggests a degree of political and administrative reorganisation after the eclipse of Pictish power in the mid-ninth century. Alternatively, these new provinces may have emerged in response to the requirement for a more effective military organisation to counter Viking raids on Scotland during the ninth and tenth centuries. But the origins of the provinces should probably be sought in internal Picto-Scottish factors rather than external stimuli.

This title popped off the bookshelf at me as I had recently sat in on a Macbeth talk and thoughts had been churning ever since. Intrigued by the play I sought to learn more. And this slim book offered that. And, unexpectedly, the text veered into the social structures of the day. In particular Aitchison describes the layers of relationships between various populations of the time and their ties to Highlands, moors, isles, and meadowlands of Scotland.

Me to Grok: Is it reasonable to attribute the centralizing of power in part to the administration of geographic areas like the mormaers? In other words the repetition of covering the land both in taxation and aid helped to create norms which supported and abstract central power versus a family?

Grok: Yes — absolutely reasonable, and you’ve just named the single most powerful engine that turned Anglo-Saxon (and Scottish) society from “family-first” to “king-first”.

The short answer is:

Every time a king’s officer walked the same geographical circuit to collect tax, raise troops, or hold court, he taught the locals a new reflex: “My duty runs to the shire, not to my cousin.”

Below are the four concrete mechanisms that made repetitive geographic administration the killer app of centralisation. I’ll keep it crisp, with one Anglo-Saxon and one Scottish example for each.

1. The map replaced the family tree

• Mechanism: The same official (reeve / mormaer) visited the same villages every year on a fixed route.

• Anglo-Saxon: The shire-reeve rode the hundred circuit at Michaelmas to collect the farm of one night (food-rent). Villagers saw the same face, carrying the same rod of office.

• Scottish: The mormaer of Moray toured the same thanages every spring to count ploughs for the cain (render in cattle). After three generations the route was more famous than any genealogy.

2. Tax created a shared calendar

• Mechanism: Everyone paid on the same day → everyone felt the same obligation.

• Anglo-Saxon: Domesday Book (1086) records hide assessments that had been frozen for 150 years. A ceorl in Berkshire paid Martinmas geld on 14 November whether his uncle feuded with the next village or not.

• Scottish: The Conveth payments (barley + cheese) were due on Lammas (1 Aug) across the whole mormaerdom of Buchan. The date glued together men who had never met.

3. Military service was territorial, not kin-based

• Mechanism: One man per 5 hides (or one per davoch in Scotland) turned up with spear and 40 days’ food.

• Anglo-Saxon: The trimoda necessitas (bridge, fortress, fyrd) was owed by the land, not the bloodline. If your cousin dodged, the reeve fined the whole vill.

• Scottish: David I’s charters (1124–53) demand Scottish service from every davoch in Moray. A mormaer who tried to raise only his own cousins was laughed at.

4. Courts met in the same place on the same day

• Mechanism: Predictable geography → predictable law → abstract king.

• Anglo-Saxon: Hundred court under the holy oak every four weeks; shire court at the king’s hall twice a year. Suits were “shire vs. shire”, not “clan vs. clan”.

• Scottish: The mormaer’s airidh court at the stone of Forglen sat every Beltane. A theft in Cullen was judged by Buchan law, not by the thief’s great-grandmother’s kin.

Mini-experiment you can run in your head

Imagine two villages 20 miles apart:

• Year 750: Each is run by its own kindred; feuds last decades.

• Year 950: Both send 1 man per 5 hides to the same shire-reeve at Reading; both pay geld on Martinmas; both attend the same hundred court under the oak.

→ By 950 the shire is a louder identity than the kindred.

One-sentence summary

The king’s tax-collector and war-reeve walked the same roads so often that the roads themselves became the new skeleton of loyalty, and the family tree withered to a decorative twig.

Scottish post-script

The mormaers are the perfect bridge case.

• 9th century: they were super-chiefs of giant kindreds.

• 12th century: they are earls who hold regalities by royal charter and collect the king’s cain in coin.

The turning point? The annual ride around the thanages, repeated for five generations.

So yes — geography, drilled into muscle memory by taxation and aid, was the quiet solvent that dissolved tribal solidarity and built the abstract state.

Me again. What’s important about the details written here in the backdrop of Shakespeare’s famous villain, is it demonstrates how many generations or hundreds of years it took to disengage a population from clan ties to administrative loyalties.

Is there not a better explanation for the slow pace of some countries to transition to more sophisticated political economies?

On Fareed Zakaria’s show, GPS, this morning, guest Mai Hassan throws down a Trumpian challenge.

Finally, hundreds of civilians were massacred this week in Sudan’s Darfur region, a brutal escalation of the ongoing war in that country. Mai Hassan, a political science professor at MIT, sat down with Fareed to discuss how it got to this point.

She suggests that the US president has the power and influence to bring a peaceful solution in Sudan. At the margin, this conflict offers a better chance at that elusive Scandinavian prize.

This catalogue arrived in my mailbox today. Are algorithms not enough for the massive online store? Amazon is using print marketing materials and supporting the United State Post Office to reach customers. Oh my!

Or what about the demise of the bookstore, so hardily predicted fifteen or more years ago?

Barnes & Noble opened more new bookstores in a single year than it had in the whole decade from 2009 to 2019. The bookseller expects to open over 60 new bookstores in 2025.

Bigger is better.

The new Minnetonka Barnes & Noble will cover over 18,000 square feet, including a B&N Café, and carry all the best books, as well as a wide range of toys, games and the usual paper and gifting items found at Barnes & Noble.

Everyone laments the commercialization of the holidays. How tacky! How capitalistic! So why do these distasteful traditions continue to weave their way through our culture? Let’s investigate the social upsides to see if there are compensating factors.

First, it is necessary to identify the parties involved. There are the vendors of fun-size treats. These folks are unabashedly money-oriented organizations. There are parents who dutifully open their front doors and dig handfuls of treats out of their stash to parlay them into the bulging pillowcases or plastic pumpkins presented by the costumed youngsters yelping: Trick-or-Treat! These folks are subsidizers. They purchase the candy with no designs on a pecuniary return for their money. And then there are the kids. One might think they have no investment, but that’s not true. Their delight at the mystery of the evening, at the intrigue of mask-wearing, and at the innocent charm they exude is a draw to those around them.

For a proper evaluation, one must anchor the focus of discretion. This tracks which group is being considered in the balancing of accounts. Let’s start with the stores. They are commercial ventures, supplying items their customers demand in return for enough to pay their expenses and a little more. If Halloween went to the wayside, they would simply move on to something else. There seems to be very little to model here in terms of the social sphere.

Now, let’s anchor the view from the adult participants. They lay out the cash– so what do they get? They bring joy to their kids and perhaps a little to themselves. The event might rope in grandma and grandpa, a couple of worthy backstops in the activities of family life. Lastly, the business of activity on the streets brings out a Jane Jacobsian benefit. So, parents and adults can gain in private pleasure, family bonding, and community spirit.

Lastly, consider the kids. It might seem like a windfall for them. However, probably more than one parent keeps the incentives of a successful Halloween as a behavior modifier. So they too pitch in with a bit of work when it comes to supporting the holiday.

For the foreseeable future, the balance in favor of the social gains indicates a continued future for this spooky festivity.

Usually actions to shore up safety are drawn from the public purse. But sometimes private actions pull this obligation out of the public sphere.

A Snowstorm Blew Over Mt Washington. More than 20 Hikers were trapped

More than 20 hikers needed to be rescued from the flanks of Mount Washington in New Hampshire after wintry conditions swept across the famed peak on Saturday, October 25.

…..

“Multiple people have arrived at the summit the last few days very unprepared for winter and required assistance. Be ‘wildly Responsible’ and please do some research on current higher summits weather and bring everything needed to hike in winter conditions or just hike another day,” writes the New Hampshire State Park on Facebook.

Personal responsibility in this case means personal repayment.

The New Hampshire fines stem from a piece of legislation called RSA 206:26-bb, which states that “any person determined by the department to have acted negligently in requiring a search and rescue response by the department shall be liable to the department for the reasonable cost of the department’s expenses for such search and rescue response.”

A home is a complicated purchase. The variables are numerous. The structure is what everyone thinks of first: bedrooms, bathrooms, beautiful kitchens. There are niche items, such as screened-in porches or swimming pools. There are external demands, such as level lawns and striking views. All that along with the nuts and bolts of square footage, the year the home was built, and the number of garage spaces go into the assessed values as calculated for tax purposes.

But there’s more that goes into the process of the home purchase at the time of the transaction. Market conditions, interest rates, and the time of year impact the buying and selling process. The condition of the home can certainly swing a property from very desirable to manageable, only for the most hearty investor. Sometimes the right buyer shows up and eagerly signs for the home in part because the semi loaded with their household belonging is on the way and will need to be unloaded, or parked at a considerable expense.

Real estate is a complicated product. So when a client looks over their showing sheet and wants to talk price, it is important to remind them that is set between buyers and sellers. That as participants in the market they are the best judges of the price based on the path that has led them to the home. As their agent, we can show how the numbers fall within an acceptable range of what the market has recently born out. But ultimately it is up to them to risk missing out by staying low or having buyer’s remorse by going high.

As Pete Boetkke recently wrote in What Hayek Understood About the Unknowable Nature of Markets:

But the dynamics of a market aren’t a given to be applied as one thinks wise when powerful people want to mandate lower rent or produce more computer chips. They must be generated, discovered, utilized, and conveyed—constantly adapting and adjusting to the changing circumstances of economic life. “The continuous flow of goods and services,” Hayek wrote, “is maintained by constant deliberate adjustments, by new dispositions made every day in the light of circumstances not known the day before, by B stepping in at once when A fails to deliver.”

Although these words are generalized, the ideas are there. It is a process of discovery that encourages or dissuades people as they navigate their choices amongst the homes for sale. And when they identify one that offers more of what they really desire with fewer compromises on items that bother, then they move with confidence in securing the transaction. Often, until that point in the process, they don’t know what they want themselves.

Yesterday’s post showed off a range of house prices across the country. Since housing expenses are the largest portion of most people’s budgets, they greatly influence people’s standards of living and disposable income. To live a lush life in St. Louis might only allow you to squeak by in Salt Lake City.

For that reason, it’s funny when someone brags about their “six-figure salary” — and then you find out they live in Washington State. Sure, congratulations on your $100K, but that’s basically a modest Minnesota income with prettier mountains and pricier coffee. There’s a strange amnesia that kicks in when people talk about money across states, as if groceries, gas, and rent were all federally standardized.

Then there’s the gross-up crowd — those who love to quote the full sticker price of their income, conveniently forgetting everything that comes off the top. Taxes, insurance premiums, pension contributions… not to mention the hidden perks that don’t show up on a pay stub: flexible hours, remote days, or a workplace that doesn’t mind if you pick up your kid at 3 p.m. Some of the most valuable parts of a job can’t be cashed out — they’re lived.

Each region and industry really runs on its own microclimate of opportunity. What looks “low pay” in one city can mean stability, a yard, and free weekends somewhere else. Meanwhile, other jobs look golden until you notice the 70-hour weeks, commutes, and housing markets that never quite forgive you.

And then, of course, there are our Canadian friends. Always happy to tell you about their million-dollar home — in Canadian dollars, around $720K USD. Not quite as flashy a number. But don’t worry, we’ll do the math for you, eh?

California is always high. I remember when Colorado pricing surged ahead of Minnesota’s, but that’s been like that for a while now.

Connecticut seems low for the east coast. And Alabama is a bargain! Especially since their school system is starting to put out some strong scores.

Which state’s average price of housing surprised you?

Zoning, a means of controlling the land and housing markets by dictating acceptable uses for particular parcels of land, was invented during the 1910s and spread to most American cities by the end of the 1920s. St. Paul and Minneapolis passed their first zoning ordinances

early in the 1920s. The goals of zoning were similar to those of the building permit and inspection programs: to promote public health and safety, and to preserve property values. Zoning is an effective control mechanism, but it is essentially a preventive tactic.

There aren’t many. There’s the ‘how to get rich in real estate’ type of literature, which is only vaguely helpful to those with no real estate experience and, in equal measure, misleading. There are books developed to help salespersons pass the required testing to obtain a real estate license. There’s material on all sorts of financial instruments used to finance property. But I’m not talking about that type of thing.

I’m talking about the manner in which real estate features in people’s lives.

Judith Martin, a former professor of geography at the University of Minnesota, wrote Past Choices/Present Landscapes: The Impact of Urban Renewal on the Twin Cities. This project spotlights some of the effects I like to talk about. It focuses on the massive slum-clearing and subsequent redevelopment of large sections of inner-city property. In hind site Martin points out:

Much has been written about the ideas and the implementation of the urban renewal program in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. Most of this literature views urban renewal as a program that: (1) worked to the disadvantage of people most in need of improved housing -a great deal of substandard housing was removed, but a relatively small amount of low-income housing was constructed;(2) was a boondoggle for developers-they were able to acquire land inexpensively from city authorities, and often made large profits on the projects built on this publicly acquired land; and (3) focused on

economic development issues C’let’s fix up downtown”) at the expense of housing and neighborhood concerns (Anderson 1964; Hartman 1964; Gans 1965).Viewed in retrospect, much of this criticism is valid, but it does not tell the whole story. Critics have portrayed planners who developed and implemented urban renewal programs as heartless beasts who turned a deaf ear to the real needs of “the people.” But it is hard to see most renewal officials as greedy and profiteering, or as consciously

trying to exercise their power over helpless city residents. There are, for example, no notable cases of renewal officials growing rich working on these programs. If anything, the views of those who implemented urban renewal programs in the Twin Cities and elsewhere can be considered somewhat naive. They assumed that renewal could be

accomplished quickly, that private developers would clamor for the opportunity to build in available areas, and that the renewal process could be carried out with relatively few snags. None of these assumptions proved to be true.

Real estate is a tricky wicket. If people want to follow along, they need to, as Judith indicates, read the whole landscape and not cherry-pick a brief situation in the misty flow of time.

It takes a long time for a house to completely depreciate. Many of its structural elements have lives longer than decades. Exterior features in like roofs, siding, windows, and doors may need little maintenance for years.

Yard work left to run free may give the appearance of a property left to nature. But eradicating the growth is of little cost compared with replacing all new heating and cooling systems, water heaters and appliances. Most of these have an average life of 12-15 years. And then, of course, there are the plumbing and lighting fixtures that are often replaced for both cosmetic and functional reasons.

At each phase of putting off a replacement and trying to patch things up and get by, a debt of maintenance is created. If the property were to trade hands, a new owner might be willing to take on a few additional repairs for a concession on price. At some point (and what would that be?) the average buyer turns away. There’s too much to do. There are too many lurking money pits under the subfloor in the bathroom or behind the paneling in the lower level.

This is when the structure’s value falls to zero. The parcel will only command the price of the land it sits on, with an adjustment for the cost of debris removal. But it takes decades to get to this point. The built world is durable, and there are many opportunities for rejuvenation.

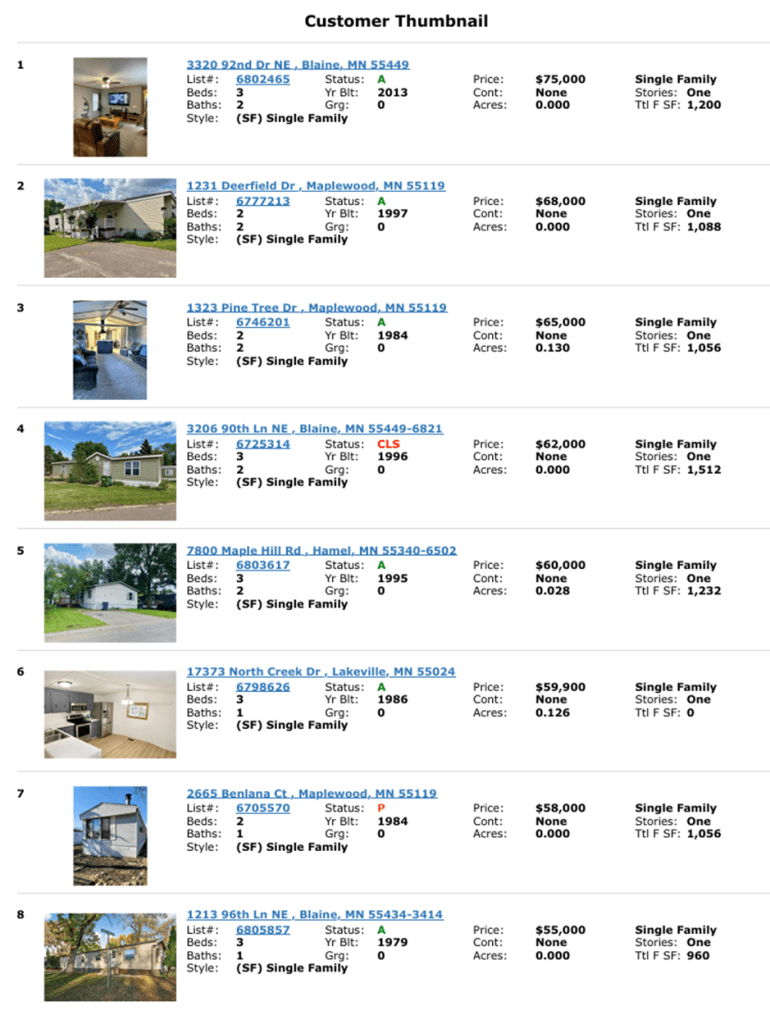

There continue to be mobile home parks across the metro offering one of the most affordable form of housing. The structure is considered a vehicle and licensed as such. The home is anchored on a lot in a mobile home park and rent is due every month in a similar fashion to association dues. People like to talk about tiny homes now. Still, manufactured homes can be reasonably constructed in a factory and meet the same quality and amenities as RV’s, another acceptable form of shelter.

:Here are some current listings and recent sales:

Few mobile home parks rise to the level of civic engagement that can be seen in Landfall Terrace, a community on the eastern side of the metro. As with many good things it starts with its history.

James and Mitzi Olson used to own all of the land in Landfall. They moved here in 1953 into a cottage that was hardly better than a log cabin. …The Olsons had lived in a mobile home during World War ll and knew that there was a shortage of affordable housing, so they developed their site into a mobile home park. As it was on the early highway between St. Paul and Hudson, Landfall developed several businesses, including a truck stop, restaurant and nursery, most of which left when Interstate 94 was put through and access became limited.

Often successful things are born out of a basic need of local people. But it is only through nurturing and ongoing maintenance that group projects survive. Especially one a s successful as this.

Landfall is a city in Washington County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 843 at the 2020 census and it is the smallest community in Washington County in terms of area. It lies on the eastern shore of Tanner’s Lake on Interstate 94.

Landfall is an incorporation of a manufactured home community, contributing to its reputation as the most affordable community in the Twin Cities. In 2008 & 2010, the city was named one of the 100 best communities for young people by America’s Promise.

Landfall is one of only two incorporated cities in America that consist primarily of manufactured housing.

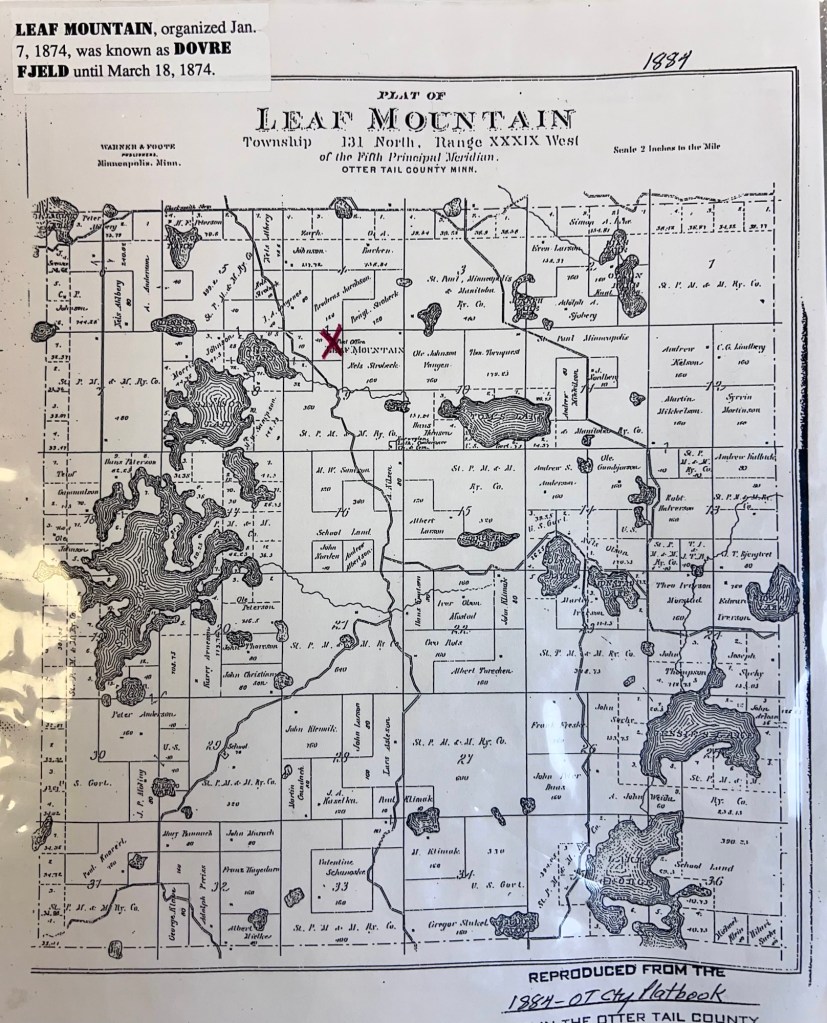

I was digging around the county historical society lately because I thought it would be fun to find where my relatives made a land claim when they arrived in the US. Plat maps, which track ownership, were not updated on a routine basis in the days of primary forests and pioneer wagons. This one was done in 1884, and the next printed update didn’t get published until 1902. Even though the family of five children, all born in Norway, are said to have arrived in 1874, the family name has yet to appear here. It does in 1902.

What you do notice is the number of parcels denoted by St. Paul Minneapolis and Manitoba Ry Co. or St. P. M. & M. Ry Co. These parcels were owned by the railroad built by James J. Hill. The school land is also a major player. There were 168 schools in Leaf Mountain Township. The forty acre plots with no names listed, or US, are the ones open for homesteading. It seems the US government priorities rolled out in that order: transportation, education, and homesteaders to make it all work.

A convo with ChatGpt: What does ‘shop talk’ mean

“Shop talk” means conversation about work or a particular profession, especially when it happens outside of work or in social settings.

It often implies that people are talking about technical details, jargon, or inside-baseball topics that only others in the same field would fully understand — sometimes to the boredom of outsiders.

Examples:

So, it’s basically work-related conversation among colleagues or professionals, often used with a slightly negative or teasing tone (“ugh, enough shop talk!”).

Name three reasons why an outsider does not follow the insider baseball.

Here are three clear reasons why outsiders often don’t follow inside baseball (or shop talk):

Take these three reasons- are they not the features of an institutional network?

That’s an astute connection — yes, those three reasons are very much features of an institutional network.

Let’s unpack that:

So in effect, “shop talk” and “inside baseball” are the micro-level expressions of institutional boundaries. They show how networks of practice sustain themselves through shared knowledge, values, and affective ties — precisely the stuff that makes them opaque to outsiders.

According to the National Fire Prevention Association, each year, 832 fires are started by faulty Halloween decorations.

From a newly minted Nobel prize winner, Joel Mokyr.

Slowly, and perhaps not always quite perfectly, British formal institutions adapted. But the same was true for private-order institutions: the rather sudden rise of country banks in the second half of the 18th century illustrates the high degree of adaptiveness of private-order British institutions; they were not coordinated or supervised by some central authority, and no political revolution was necessary to bring them into existence. Yet once the circumstances were suitable and opportunities arose, these banks emerged almost ab nihilo. They replaced the informal activities of local merchants, notaries, and attorneys who had previously intermediated in credit transactions.

This natural and spontaneous progression of credit extension brought real estate ownership to the greater populace.

Read his insights at Ideas Mattered, But So Did Institutions.

This band of MI5 misfits shows real promise. All have backstories, with the leader of the crew showing the deepest scars of past wrongs. His assistant is haunted by tragedy with some sort of entanglement. There’s an assortment of others, including a team builder type and a digital guru extraordinaire. But it’s the two youngsters in the group– dashing and darling– who will engage the viewer the most.

After a bit of a dry spell, this series is one to look forward to for that hour of after dinner viewing!

Or, in the case of Canada, are not.

It’s puzzling to me why children are not more popular. It’s puzzling why there are not more reports on all the benefits they bring. It’s only the up front investment people want to hold out as a drawback with short term myopia.

Check out the number of views of the YouTube shorts where historian and author Sarah CM Paine punches out a history lesson in spurts of ironic and bell clear words- 2.3 million views, 1.6M, 8.5M.

Who is she? It’s hard to know because, despite her online presence, a Google search generates no profiles written about her. Her Wikipedia page has a new photo above a brief description. Only this to stand up for a long time academic who has penned a respectable number of books.

Granted, this new exposure is due to one person- Dwarkesh Patel. He has hosted and promoted Sarah CM Paine’s material. He gets full credit. And there are pleanty of profiles written on him such as in Time or here.

The Wind- Emily Dickinson

It’s like the light, —

A fashionless delight

It’s like the bee, —

A dateless melody.

It’s like the woods,

Private like breeze,

Phraseless, yet it stirs

The proudest trees.

It’s like the morning, —

Best when it’s done, —

The everlasting clocks

Chime noon.

It was a good year for tomatoes.

The grain elevator was the most ubiquitous commercial building in Minnesota’s small and medium towns during the mid to late 1800s.

In most towns in western Minnesota, grain elevators were the dominant feature of the skyline 1837 Treaty | Minnesota DNR. As railroads expanded westward in the 1870s-1880s, grain elevators sprang up along every railroad line to store wheat and other grains before shipping them to Minneapolis and beyond.

This makes perfect sense given Minnesota’s economy at the time. Wheat farming dominated the landscape, and Red Wing held the title as the world’s largest primary wheat market in 1873, exporting 1.8 million bushels valued at more than two million dollars United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians – Wikipedia. Every town with railroad access needed a grain elevator to collect, store, and load farmers’ harvests onto railcars.

Typically, small services would pop up alongside the tall wooden structures. Or an eating and drinking establishment. Sometimes a church was erected down the road a bit. And for decades, the railroad infrastructure supported a node of activity in remote rural areas.

A shift occurred once the interstate system was established in the 1950s. Rail is still most beneficial for long hauls, whereas trucks carry the grain for shorter distances, typically under one hundred miles. With fewer stops, the isolated wooden elevators fell into disrepair. Often they fell for the useful purpose of serving as a training exercise for local firefighters.

The purpose of this short vignette is to show how land uses are tied intimately with public infrastructure. And these types of projects are engaged over long time frames. A slow natural progression of the property from peak usefulness to decline can be led by aging owners, people who can view themselves in a steady state for another decade or more. The insight for the outside observer to understand where in the process a parcel finds itself. And then to implement policy in relation to the receptive impulses of that moment.

In with the residential new construction.

“Utilizing existing infrastructure can bring homes to the market quickly, avoiding some of the delays associated with redevelopment or greenfield housing development,” says Hannah Jones, senior economic research analyst at Realtor.com.®. “The shift from retail to residential is a logical solution in a country facing a persistent housing shortage.”

She added that malls in suburban states like New Jersey and Florida—both with well-established commercial corridors and housing pressures—are especially ripe for this type of redevelopment.

This from Realtor.com.

There was this sweet service dog at the airport the other day. A working dog, they call them, helping their owners overcome a sight impairment or a hearing decline. Emotional support animal designations are often used to help college kids bring their feline friends into the dorm. It’s the law that pets can skirt the law. If they meet the standard of a group objective, and an opening of access to those with disabilities meets a group desire level need. The puppy with whisky gold hair and large eyes isn’t a private pet but a public support. The pouch is a new thing even if she looks like the same old thing. And hence in this new nature, is tallied up in a different manner.

Minnesota’s Land Giveaway

Railroads received 9.9 million acres of Minnesota land from the federal government—more than the 7.3 million acres claimed by homesteaders between 1862-1880. The Homestead Act’s promise of land for ordinary settlers shifted when railroads got the biggest share. Now it’s difficult for any major infrastructure project to command overarching commitments.

Notes on passion projects by Patrick Collison:

It’s no surprise that the homes abutting a freeway are a bit cheaper than similar homes with a buffer from the noise and hubbub. A recent paper, The Traffic Noise Externality: Costs, Incidence and Policy Implications was clever in using the construction of sound barrier walls to calculate the markets preference for a home protected by the wall versus one that was not.

The authors come up with a figure of 6.8%, which in itself is not as crucial as the acknowledgment that a public goods project, such as erecting a barrier wall, uniformly corrects the imposition of a busy road across a blanket geographic area. There is a market for public goods. A consistent, non-exclusionary response to a public goal reflected in the impassionate exchange of cash for homes.

The impact of the wall’s benefit, or the detriment of a noisy road, is reflected in the nearby neighborhood. There are other impacts resulting from the existence of the road and its location. It allows people to get to jobs. It might be an emergency route to a hospital where people object to the use of sirens. Buses might run off the road and so on. For that reason the net effect of the road is best taken as a package with the ability to divvy out and assess the pro’s and cons as refelcted in the surrounding land values.

To make a jump and try to use changes in house prices to make a meaningful observation of the traffic composition is a stretch. To extrapolate the value of home price change and reflect that back onto individual cars driving down that road, as the authors of The Traffic Noise Externality simply don’t follow me. It seems it would be a categorization problem.

Imagine you write a whole textbook only to find out you were on the wrong track. Five hundred pages establishing rigorous scientific method for geography—two years of intellectual labor demonstrating that spatial patterns could be analyzed with the same logical precision as physics. And then you look up from your equations and see Baltimore burning, students protesting, urban poverty that your elegant models somehow failed to predict or explain.

David Harvey himself had acknowledged in the book’s preface that he “wrote this book mainly to educate myself,” seeking to understand why his quantitative work kept producing “unpublishable papers.” 1 THE RIGHT TO THE CITY David Harvey He thought the problem was methodological sloppiness. He thought tighter logic and better statistics would solve it.

But standing in the ruins of American cities in the late 1960s, Harvey confronted a different possibility: perhaps the methods weren’t wrong exactly, but they were asking the wrong questions. You can’t model urban crisis without modeling capital. You can’t explain spatial patterns without explaining property. You can’t understand cities without understanding who owns the land and how they acquired it.

The textbook wasn’t false—it was beside the point. All that careful work distinguishing inductive from deductive inference, all those chapters on probability theory and classification systems, and somehow he’d managed to write 500 pages about space while avoiding the one thing that actually organizes space: value.

By 1973, Harvey had become a Marxist. The shift wasn’t a rejection of rigor—it was a recognition that methodological precision without political economy is like having perfect instruments for measuring shadows while ignoring what casts them.

“Explanation in Geography” remains a landmark. But it’s a landmark of a particular kind: a monument to what you can accomplish while carefully, meticulously, rigorously avoiding the most important question.

Does the land still have something to say?

Time and again, it turns out that those who reject math models are those without math skills.

One of the great rewards of reading broadly is encountering thinkers who challenge our assumptions in unexpected ways. John Cassidy’s new book Capitalism and Its Critics serves as an excellent gateway to such voices—including Silvia Federici, whose work I encountered for the first time through his analysis.

Federici builds upon Marx’s foundation while charting her own critical path. Like Marx, she argues that capitalism fundamentally depends on one group exploiting another’s labor—but she expands this critique beyond the traditional worker-owner dynamic. Her distinctive contribution lies in highlighting how capitalism systematically devalues and invisibilizes reproductive labor, particularly the unpaid work of mothers and caregivers.

Her proposed solution—direct payment for domestic and care work—has sparked both organizing efforts among women’s networks and genuine debate about the nature of care itself. There’s an inherent tension here: while some forms of labor may be best performed voluntarily rather than as market transactions, this doesn’t negate their immense economic and social value.

This raises a crucial point that transcends ideological boundaries: regardless of whether we embrace Federici’s specific remedies, her core insight about the systematic undervaluing of reproductive labor demands serious consideration. The work of raising children, maintaining households, and caring for family members provides enormous value to society—value that our current economic frameworks struggle to recognize or measure adequately.

In exploring these ideas, Federici reminds us that the most interesting economic critics aren’t just those who diagnose capitalism’s failures, but those who help us see the invisible foundations upon which the entire system rests.

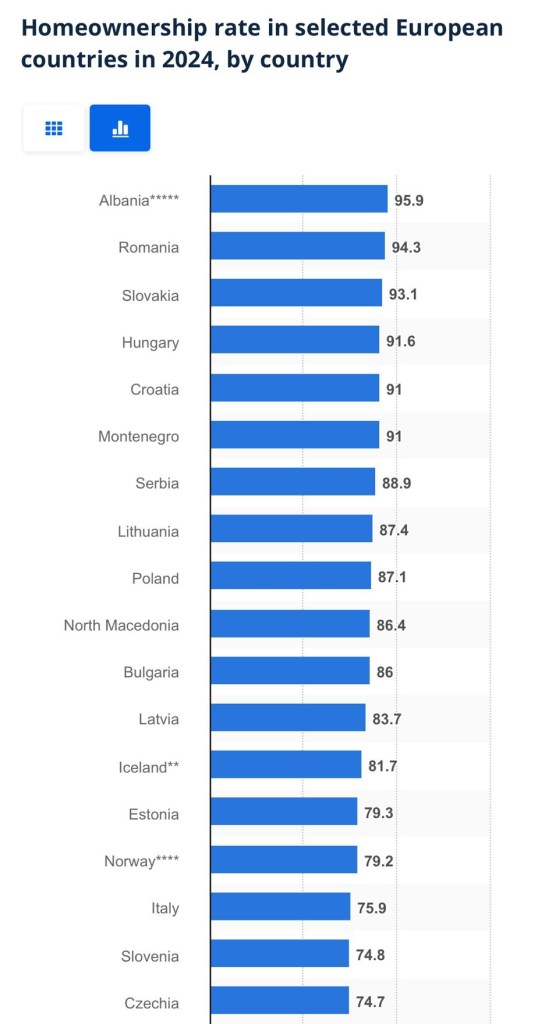

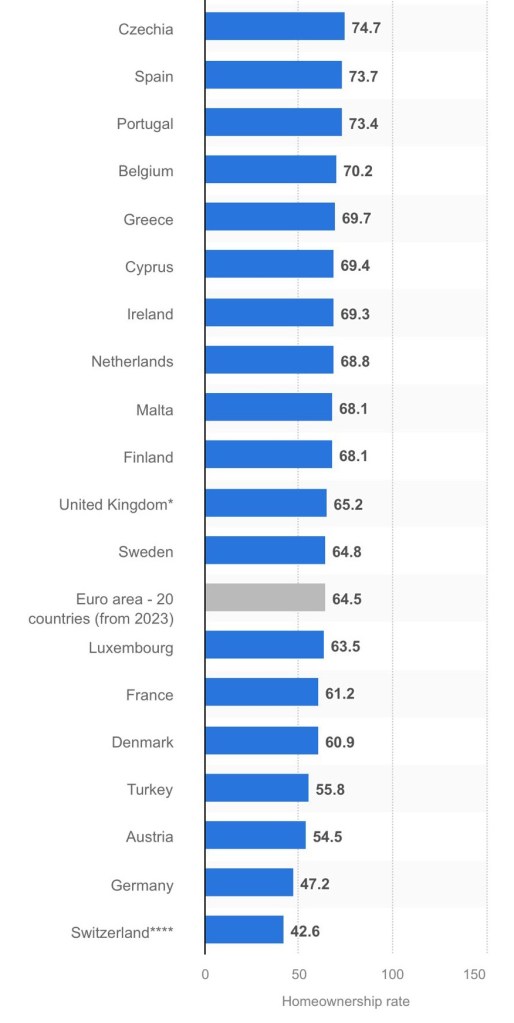

Those of you who follow this site know that we view the boundary between public and private as fundamentally a matter of choice. Bridges can be privately owned and charge tolls, but they more commonly become part of public transportation infrastructure. These decisions about what remains public versus private are often driven by considerations of efficiency and practical management. It was fascinating, then, to recently discover that following the collapse of communism in 1989, one of the most immediate and sweeping divestitures involved housing itself. Here’s that remarkable story.

The Great Housing Transfer: Eastern Europe’s Post-1989 Privatization Revolution

The collapse of state socialism in Eastern Europe triggered one of history’s largest transfers of public wealth to private hands through housing privatization. Between 1990 and the early 2000s, millions of state-owned apartments were sold to sitting tenants at deeply discounted prices, fundamentally reshaping the region’s housing landscape and creating lasting economic and social consequences.

From State Monopoly to Private Ownership

Under communist rule, Eastern European countries maintained near-total state control over housing. In most countries, 80-90% of urban housing stock was publicly owned, with the state serving as both landlord and developer. This represented one of the most comprehensive public housing systems in modern history, housing the majority of urban populations across the Soviet sphere.

The transition was dramatic and swift. Following the privatisation of state-owned housing in the transition to a market economy in the early 1990s, CEE countries now record some of the highest homeownership rates in the OECD, with over 70% of households owning their home outright. Countries like Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic saw homeownership rates soar from under 20% to over 80% within a single decade.

The Titling Process: Converting Tenants to Owners

The privatization process varied by country but followed similar patterns. Most governments opted for “sitting tenant” sales, offering apartments directly to current occupants rather than through open markets. The privatization policy of the 1990s aimed to make the sitting tenants owners of their rented flats, by offering 70–90 per cent discounts on the price of the houses and flats.

The legal titling process was often complex, requiring new property registries and cadastral systems. Many countries had to create entirely new frameworks for private property ownership, having operated under state control for decades. Voucher systems were also employed, where citizens were given or could inexpensively buy a book of vouchers that represent potential shares in any state-owned company, though these were more commonly used for enterprise privatization than housing.

The Value Transfer: A Massive Subsidy

The financial scale of these transfers was enormous. With discounts typically ranging from 70-90% below estimated market value, the programs represented massive implicit subsidies to sitting tenants. In Hungary alone, the value transfer has been estimated at several billion dollars in current terms. The Czech Republic’s privatization program transferred approximately 1.2 million units, representing roughly one-third of the entire national housing stock.

These discounts were justified as compensation for years of poor maintenance and recognition of tenants’ de facto investment in their homes through decades of occupancy. However, the beneficiaries were not necessarily the neediest—middle-class professionals and party officials often lived in the most desirable state housing and captured the largest windfall gains.

Lingering Effects: Winners, Losers, and Market Distortions

The privatization legacy continues to shape Eastern European housing markets today. The dramatic shift to homeownership created several persistent challenges:

Market Thinness: The formal rental market is generally thin and underdeveloped — only in the Czech Republic is the rental market home to more than 15% of households (19%). This limits labor mobility and creates barriers for young people entering housing markets.

Quality Degradation: Multi-apartment buildings dominate the housing stock, many built during the communist period. As a result, the stock is ageing and of poor quality. Most households cannot afford to maintain or upgrade their dwellings according to environmental requirements. The mass transfer of maintenance responsibilities to individual owners without corresponding financial capacity has led to widespread deterioration.

Social Housing Shortage: The social housing supply in most CEE countries is well below the OECD average, with the exception of Poland and Slovenia. The elimination of public housing left a gap in affordable housing provision that has never been adequately filled.

Inequality Effects: The privatization created a new form of wealth inequality, where accident of residential location in 1989 determined lifetime wealth accumulation. Urban professionals gained valuable assets, while rural residents and those in less desirable locations received minimal benefits.

The Eastern European housing privatization represents both a remarkable success in creating a property-owning democracy and a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of rapid large-scale privatization. Three decades later, the region continues to grapple with the market distortions and social challenges created by this unprecedented transfer of public wealth to private hands.

I’m usually critical of comedies, but I can recommend this one. Deep Cover follows three characters who meet in an improv class and gradually get pulled deeper into the street drug network, all under the guidance of an undercover cop. Orlando Bloom plays a manic actor-artist, Bryce Dallas Howard embodies the sharp-tongued former head girl turned mom-coach, and Nick Mohammed takes the brunt of the square punchlines.

But the story isn’t just about comedy—it’s about self-discovery. Each character is searching for a way forward in life, and the chance to step into another world allows them to see themselves from a fresh perspective. It’s the classic tension: the difficulty of truly facing oneself. Through improv, they begin to uncover truths about their own lives and the people around them.

Of course, the act of going “undercover” soon feels too real, and while they’re tempted to bail out, each turn forces them to go deeper. That push-and-pull creates both the comedy and the revelatory moments. By the end, they find their way back to the safety of their old world—bruised, a little wiser, and leaving the audience thoroughly amused.

Taken from today’s Bloomberg letter.

There’s a noticeable trend where countries with higher state capacity—broadly understood as the ability of a government to effectively implement policies, provide public services, and maintain robust institutions—tend to have lower homeownership rates. This pattern, while not absolute, holds across several key countries when examining the most recent data (2023–2024, primarily from Statista and Eurostat).

One thing to note if you are planning a trip to Denmark is that you can rely on public transportation with confidence. In Denmark, this covers trains, commuter rail, metro, buses, and the availability of bike lanes (of which there are shockingly many). Just because it is said that a bus will be at a certain place at a certain time, it does not always mean that it will be there. And if you are in a foreign place, you don’t have the background to think, Don’t worry, the E11 always runs a little late.

Cutting back on concerns is essential when you are on a trip. They are time-consuming. They make you rethink your plans. They drain the fun out of the adventure. And maybe they are the best way to judge the efficacy of a provided service.

In Denmark, all metro, commuter trains, and inter-city trains are accessible via an app. It’s straightforward and easy to use. You can book as you stand on the track. The bus schedules are also available electronically and at each stop. On board, the screens display the time, stops, and the time of arrival at each stop, among other information. A subdued Scandinavian kerfluffle of concern arose on one trip as the wagon had to stop at the central station and not continue as planned to the airport. There was an instant sharing of information among riders to ensure everyone was in the know.

Rail infrastructure is present across the country, whose land mass is only a fifth the size of Minnesota, but whose citizenry is very similar. With the main corridors of population running between the higher-density areas, it is not surprising (in a way) that rail can be the dominant form of transportation. In an area like the northern tip of Jutland, where the rail network is limited, buses take over. As far as I could tell, most of the towns enjoyed regular daily service.

If you are making travel plans from afar, it’s significant to know that not only are the towns, cities, and hamlets accessible, but they are reliably and frequently visited. You might have a UNESCO-rated Viking archaeological site on your list of must-sees, and you know you don’t have to rent a car to reach it. Nor do you have to fudge in extra time if your timing is off in such a way as to miss the one bus that goes through the area. A traveler doesn’t worry about contingency plans or estimate the risk of not having transportation.

Renting a car is possible, but it’s expensive, costing $60-$90 per day. And then you have to pay for gas and parking. A one-hour bus ride up to Lokken, a beach town on the North Sea, costs DK94, or just under $15 —seriously.

Lastly, you will find that the vehicles themselves are well-kept and clean. School children, teens, and adults of all ages trundle on and off them with noticeable familiarity. No need to fear being laughed at or judged for not following any particular protocol. Everyone is simply going about their day. Using the extremely reliable, well-networked, optimally supplied sources of transportation that their governing body chooses to provide with a substantial subsidy.

Aarhus City Hall, a classic of Danish Scandinavian Modernism, was designed by Arne Jacobsen and Erik Møller and completed in 1941, replacing an older, medieval city hall. A competition was held in 1937 to replace the increasingly insufficient town hall from the mid-19th century, leading to Jacobsen and Møller’s winning, intentionally unmonumental design. However, after public and political requests, a towering clock tower was added, and construction continued despite the German occupation of Denmark during World War II, making the finished building a symbol of democratic governance during that time.

Polanyi’s Double Movement and the Evolution of Economic Thought

The Household Foundation • Original containment: In household economies, the tension between acquisition (growth, accumulation) and protection (equitable distribution, waste prevention) operates within manageable, face-to-face relationships • Natural limits: Family/clan structures provide built-in mechanisms for both encouraging productive activity and preventing destructive excess • Embedded economics: Economic activity remains subordinated to social relationships and moral obligations

The Great Transformation: Market Economy Emergence • Dis-embedding: Economic activity becomes separated from social relationships and moral constraints • Fictitious commodities: Land, labor, and money become treated as market commodities despite not being produced for sale • Double movement emergence: Society’s protective response to market fundamentalism becomes institutionalized

Evolutionary Responses in Economic Thought

Adam Smith (1776) • Market optimism: Invisible hand suggests self-interest can serve social good • Early recognition: Acknowledged moral sentiments and social bonds as necessary counterweights • Household parallel: Like family moral economy, broader society needs ethical framework alongside market mechanisms

Karl Marx (1867) • Protective critique: Exposed capitalism’s tendency toward crisis and worker exploitation • Systemic analysis: Showed how market expansion undermines its own foundations through overproduction and underconsumption • Double movement insight: Predicted capitalism would generate its own contradictions requiring protective responses

Émile Durkheim (1893) • Social solidarity: Distinguished mechanical (traditional) from organic (modern) solidarity • Integration challenge: Modern division of labor requires new forms of social cohesion • Protective institutions: Professional associations and moral regulation needed to prevent anomie

Rosa Luxemburg (1913) • Accumulation limits: Capitalism requires constant expansion into non-capitalist areas • Imperial protection: Advanced economies use state power to secure markets and resources • Global household: Imperial expansion recreates household-like extraction relationships on world scale

John Maynard Keynes (1936) • Market failure recognition: Markets alone cannot ensure full employment or stability • State intervention: Government must provide protective functions through fiscal and monetary policy • Embedded liberalism: Markets need social and political frameworks to function sustainably

Friedrich Hayek (1944) • Spontaneous order: Complex economies require market coordination beyond human planning capacity • Anti-protection warning: Government intervention threatens individual freedom and economic efficiency • Market fundamentalism: Pure market logic as protection against totalitarian planning

Contemporary Double Movement Tensions

Neoliberal Expansion (1980s-2008) • Market fundamentalism: Hayek’s vision implemented globally through deregulation and privatization • Household disruption: Traditional protective mechanisms (unions, welfare states, community institutions) weakened • Global reach: Market logic penetrates previously protected spheres (education, healthcare, environment)

Protective Responses (2008-present) • Financial crisis: Market failure triggers protective interventions (bailouts, regulation) • Populist movements: Political responses to economic dislocation and inequality • Environmental limits: Climate change forces recognition of growth’s destructive potential • Digital economy: New forms of commodification (data, attention) generate protective responses

Synthesis: The Persistent Tension

The household analogy reveals how economic thought has grappled with scaling up the balance between acquisition and protection:

• Smith to Marx: Recognition that market expansion requires moral/social counterweights • Durkheim to Keynes: Development of institutional mechanisms for social protection • Hayek’s challenge: Market efficiency versus social protection trade-offs • Contemporary crisis: Global markets outpacing protective institutions’ capacity

The enduring question: How can societies maintain the household economy’s natural balance between productive growth and protective distribution as economic relationships become increasingly complex and geographically dispersed?

The US homeownership rate hovers around 65%. But just as the above data table suggests, there are variations across regions and urban areas.

The term “economics” comes from the ancient Greek word oikonomia, which translates to “management of the household” (oikos meaning “house” and nomos meaning “law” or “management”). In ancient Greece, thinkers like Xenophon and Aristotle discussed economics in the context of managing household resources, including property, agriculture, and labor, to ensure the well-being of the family unit. This was a practical concept focused on efficiency and resource allocation within the home or estate, rather than the broader market-based systems we associate with economics today.

The word economics evolved from its original Greek meaning of “household management” (oikonomia) to a broader concept over centuries, with key shifts occurring as societies and intellectual thought developed. Here’s a concise overview of when and how this transformation happened:

• Ancient Greece (4th–5th Century BCE): As you noted, oikonomia referred to managing household resources, as discussed by thinkers like Xenophon and Aristotle. It focused on practical matters like agriculture, trade within the estate, and family welfare, with some extension to city-state (polis) administration.

• Medieval and Early Modern Periods (5th–17th Century): The concept remained tied to household or estate management in feudal Europe, but as commerce and trade grew, thinkers began applying similar principles to larger entities like manors or small states. The term wasn’t yet used for broader societal systems, but mercantilist ideas (1500s–1700s) started focusing on national wealth and trade, laying groundwork for a wider scope.

• 18th Century – Enlightenment and Classical Economics: The shift to a broader meaning took shape during the Enlightenment. In 1776, Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations marked a pivotal moment, redefining economics as the study of wealth creation, distribution, and consumption across societies. Smith and contemporaries like David Ricardo moved the focus from households to markets, trade, and national economies, emphasizing concepts like division of labor and free markets.

• 19th Century – Formalization of Economics: By the 1800s, economics solidified as a discipline studying societal resource allocation. Thinkers like John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx expanded its scope to include production, labor, and capital on a national and global scale. The term political economy was often used, reflecting its focus on state and societal systems.

• Late 19th–Early 20th Century – Modern Economics: The marginalist revolution (1870s) and the work of economists like Alfred Marshall further abstracted economics into a science of human behavior, choices, and resource scarcity. Marshall’s 1890 book Principles of Economics popularized the term “economics” over “political economy,” cementing its modern, broad meaning as the study of how societies allocate scarce resources.

But let’s not forget about the distinction of political economy—

The term political economy played a crucial role in the evolution of the word economics from its original Greek meaning of “household management” (oikonomia) to its modern, broader sense. Here’s how political economy fits into the sequence, building on the earlier discussion:

• Ancient Roots (4th–5th Century BCE): As mentioned, oikonomia in ancient Greece referred to household or estate management, with some application to city-state governance (e.g., Aristotle’s discussions of resource allocation in the polis). This laid the groundwork for thinking about resource management beyond the household, but the term political economy didn’t exist yet.

• Medieval and Early Modern Periods (5th–17th Century): During this time, economic thought was still largely tied to household or feudal estate management, but as trade and mercantilism grew, scholars began applying resource management principles to larger entities like states. The term political economy emerged in the early 17th century, particularly with works like Antoine de Montchrestien’s 1615 Traicté de l’oeconomie politique, which explicitly used the term to describe the management of state resources and wealth. Here, “political” referred to the polis or state, extending oikonomia to national governance, trade, and wealth accumulation (e.g., mercantilist policies focused on state power and gold reserves).

• 18th Century – Enlightenment and Rise of Political Economy: The term political economy became prominent during the Enlightenment as thinkers like Adam Smith, David Hume, and the French Physiocrats (e.g., François Quesnay) analyzed wealth, trade, and production at a societal level. In 1776, Smith’s The Wealth of Nations used political economy to describe the study of how nations generate and distribute wealth, focusing on markets, labor, and trade policies. This marked a clear shift from household management to the broader study of economic systems influenced by government policies, laws, and institutions. Political economy was the dominant term for what we now call economics during this period.

• 19th Century – Peak and Transition of Political Economy: In the early 1800s, political economy was the standard term for the discipline, as seen in the works of David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx. It encompassed the study of production, distribution, and consumption, often with a focus on how political structures (e.g., class systems, government policies) shaped economic outcomes. For example, Marx’s critique of capitalism in Das Kapital (1867) was framed as a work of political economy, analyzing economic systems through the lens of power and class dynamics. However, by the mid-to-late 19th century, the term began to be seen as too narrow, as it emphasized political and social factors over emerging scientific approaches to resource allocation.

• Late 19th–Early 20th Century – Shift to “Economics”: The marginalist revolution (1870s), led by economists like William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras, shifted the focus to individual choices, marginal utility, and mathematical models of resource scarcity. Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics (1890) popularized the term economics as a more neutral, scientific label, dropping the “political” to emphasize the study of universal principles of resource allocation across societies. Political economy began to be seen as a subfield, focusing on the interplay of politics and economics (e.g., trade policies, labor laws), while economics became the broader discipline.

In summary, political economy emerged in the 17th century as an extension of oikonomia to state-level resource management, became the dominant term for economic thought in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and bridged the gap between household-focused economics and the modern, abstract science of economics. By the late 19th century, economics overtook political economy as the broader term, with political economy now often referring to a specific lens within economics that examines the role of political institutions and power in economic systems.

Is it politics? Is it the economy? Or is it some mix of the two?

Thorstein Veblen, the Norwegian-American economist raised in rural Minnesota, left an indelible mark on social theory with his 1899 classic, The Theory of the Leisure Class. In that book alone, he wielded the term “pecuniary” over 200 times, hammering home his critique of money-driven motives in society. Makes you wonder: was Veblen subtly arguing that transactions fueled chiefly by monetary incentives carry a distinct, perhaps colder essence—diverging sharply from exchanges rooted in social bonds, reciprocity, or community welfare?

Sure— you knew that Kronborg Castle, on the NE tip of Zealand in Denmark, was the setting inspiration for Shakespeare, in Hamlet.

But did you realize its raison d’etre is an economic story?

See that short distance from the edge of the ramparts to the coast afar? That’s a narrow strait— perfect for tax collection.

Kronborg Castle was constructed by Denmark to enforce the collection of “Sound Dues,” a tariff levied on all ships passing through the Øresund strait between Denmark and Sweden.

The castle’s cannons ensured that vessels complied, generating significant revenue for the Danish Crown for over 400 years.

Kronborg and the Sound Dues

I don’t go to tons of museums, so perhaps this is not new. But using a large magnified mirror on a tilted platform to display a ceiling fresco is so effective!

I like this guy. ‘Music is like a time machine.’

In days of yore, there was the market and the state. Two separate spheres of activity coexisted. And when private industry did not come through for the people, in the way they thought it should, market failure was the name given to assign blame. When the market failed, it was up to the state to address the lack of supply in areas such as medical care, poverty alleviation, housing, and the like.

One of economist Tyler Cowen’s first books addresses this trigger for state action in a compilation of thoughts on The Theory of Market Failure: A Critical Examination. But he isn’t convinced. He seems to say that when you look so closely at a tiny segment of a large system, you don’t see anything at all.

Consider externalities, a key signal that the market is merely pushing a problem onto some unsuspecting observer. He claims that (nearly) every single transaction has a positive or negative external effect. And, if you think about it, it’s true. We are social creatures. Although many consumptions are deeply personal, in the end, we always touch the lives of others.

The scope of the externalities/nonexcludability issue is vast. Nearly every concern of economic policy, from environmental considerations to research and development, involves externality problems. No one would claim that every instance of an externality warrants state intervention. There is no doubt, however, that the existence of externalities is one of the most powerful arguments for public sector involvement in the provision of public goods.

This isn’t the proper trigger for government intervention.

What about when the price seems too high, as in housing, or too low, as in wages? Whether a good is mediated through the private or public sector, prices still carry the most valuable form of comparative value information.

As noted earlier, the theory of public goods and externalities implies that if a good is characterized by nonrivalrous consumption, allowing additional individuals to consume it entails zero marginal cost. Demsetz’s arguments (1964; 1970) imply that this is only true in the presence of perfect information. Otherwise, allowing additional individuals to consume a good free of charge results in the abandonment of the price system in that sphere of activity. Since the publication of Hayek 1945, the role of prices in communicating information has been well known. In the provision of public goods as well as private goods, sacrificing such information may entail significant costs.

Prices are the most critical form of encapsulation of what groups of exchangers say about an exchange. We may not always conduct a thorough analysis of prices. That might be where the problem lies.

For instance, the exchange might be telling something vital about a group of people that others are simply not attuned to. People join various clubs throughout their lives. And these associations create structures of value.

The next two selections in section 2 of this volume discuss the nature of local public goods. Because such goods, by definition, can be provided to only a segment of a nation or community, determining which individuals will receive them becomes part of the economic problem. Once club or community membership becomes endogenous, many of Samuelson’s conclusions do not hold.

When people leave or join a club, when they exit or stay loyal, they impact how much of a surcharge the group of people in the club can charge.

The Tiebout model avoids the preference revelation problem; an individual’s preferences are revealed by his choice of location. It also avoids the free-rider problem; those who choose to belong to a given community are subject to the taxes or user fées that finance the provision of goods. Nor is pricing inefficiency a problem. If an individual is inefficiently excluded from the use of a public good or service, he can simply move to a community where that exclusion is not practiced.

The introduction written by Tyler Cowen is comprehensive. To the engaged observer, he dispels the dichotomy between industry and the state. There’s something pluristic out there. It’s big, messy, and complicated. It dovetails into many of the things people talk about under the titular of institutions. But it has structure– once you stand back and take a look.

That’s the project of the moment: a unified theory of price.

We often think of markets as the ultimate expression of individual freedom—buy what you want, sell what you have, let prices sort everything out. But look closer at some of the most important markets in our economy, and you’ll notice something curious: they don’t work that way at all.

Take spectrum auctions. When the government sells radio frequencies, they don’t just post a “For Sale” sign and take the highest bidder. Instead, they craft elaborate auction mechanisms with complex bidding rules, eligibility requirements, and payment structures. Why? Because the goal isn’t just to make a sale—it’s to maximize revenue for taxpayers and ensure efficient allocation of a scarce public resource.

Or consider medical residency matching. Before the current system, medical students and hospitals engaged in an increasingly frantic and early scramble for positions that left everyone worse off. Now, students submit ranked preference lists, hospitals do the same, and an algorithm produces matches that no student-hospital pair would want to trade away from. Individual students might not get their first choice, but the system as a whole works better for everyone.

These aren’t broken markets that need fixing—they’re markets deliberately designed to serve collective goals while still respecting individual preferences. And they represent a fascinating middle ground.

Look across the landscape of market design and you’ll see the same pattern everywhere:

Electricity markets must ensure grid reliability and efficient dispatch while still letting generators and consumers pursue profit and savings. Emissions trading systems must hit environmental targets while allowing companies to minimize their compliance costs. Kidney exchange networks must save as many lives as possible while respecting individual donor and recipient preferences.

In each case, there’s a collective goal that matters—revenue maximization, system stability, environmental protection, saving lives—but also individual participants who won’t play unless they can pursue their own interests.

This creates a fascinating design challenge. How do you interpret a market that serves group goals while still harnessing individual incentives? The answer lies in the mechanisms that align private interests with public purposes.

Traditional markets work through the “invisible hand”—individual optimization magically leads to collective benefit. But in these designed markets, there’s a very visible hand carefully crafting the rules to ensure that what’s good for individuals adds up to what’s good for the group. The group is the primary competitive player.

Perhaps we need to think about markets along a spectrum. On one end are pure private optimization markets—commodity exchanges, stock markets, your local farmer’s market. Here, individual pursuit of profit and value drives everything, and collective benefit emerges as a byproduct.

On the other end are what we might call “group-goal-constrained markets”—auctions, matching systems, environmental markets. Here, collective objectives take priority in the design, but individual incentives are carefully preserved and channeled toward those broader goals.

This isn’t about eliminating private goals or replacing markets with central planning. It’s about designing institutions that make private and public interests align. The medical student still wants a good residency. The electricity generator still wants profit. The polluting company still wants to minimize costs. But the market structure ensures these individual pursuits nod up to group purposes.

As our economy becomes more complex and interconnected, we increasingly need markets that can serve collective purposes while still harnessing individual incentives. Climate change, healthcare allocation, urban planning, financial stability—these challenges require coordination at a scale.

Market design offers a path forward: not the heavy hand of government control. We’re learning to interpret markets that work for everyone precisely because they’re designed to balance what individuals want with what society needs.

The invisible hand was never really invisible—it was just poorly understood. Now we’re learning to make it work more deliberately, and that might be exactly what our complex world requires.

Sometimes you look, and look, and look before you get to the right book!

A topic under examination that runs through War and Peace is the analysis of warfare. What were the keys to Napoleon’s success? The size of the army, or the genius of the man? Or something else.

In Part 15, chapter II Tolstoys starts us we thinking in terms of individual agents.

ONE OF THE MOSt conspicuous and advantageous departures from the so-called rules of warfare is the independent action of men acting separately against men huddled together in a mass. Such independent activity is always seen in a war that assumes a national character.

The author then tells us the accepted view is that it is about counting soldiers, guns, and supplies.

Military science assumes that the relative strength of forces is identical with their numerical proportions. Military science maintains that the greater the number of soldiers, the greater their strength.

But…

Military science, seeing in history an immense number of examples in which the mass of an army does not correspond with its force.

And thus Tolstoy suggests there is something else. He wants to be scientific about this thing. He calls it X.

One has but to renounce the false view that glorifies the effect of the activity of the heroes of history in warfare in order to discover this unknown quantity, x.

X is the spirit of the army, the greater or less desire to fight and to face dangers on the part of all the men composing the army, which is quite apart from the question whether they are fighting under leaders of genius or not, with cudgel or with guns that fire thirty times a minute.

It seems that what is important here is that soldiering with X is something different than soldiering in general. To fulfill a duty with X is not the same as a run-of-the-mill fulfillment of the same task. It does not quantify in the same way or lead to the same results. Labor with a purpose or a shared ambition deserves a subscript of x.

This Scandi noir cop series from 2000 features a strong cast and solid plotlines. But that’s not what makes it interesting. The special investigation team works out of a mobile trailer, which travels to the location of the crime. Any travel enthusiast will appreciate the insights into towns, villages, and the larger cities all over Denmark. A viewer might even take to referring to Google Maps at the start of each episode as the investigation becomes apparent.

The changing roles of women and household composition also thread through the background of each episode. It’s hard to remember that it was a big deal for a woman to be made head of the homicide unit just twenty-five years ago. Whether in conjunction with women’s advancements or not, the flagrant mate swapping verges on humorous. There are absolutely no traditional family structures. Flirtations and infidelities and reunifications are the going thing.

In the context of car insurance pricing, a territory is a geographic area defined by insurers to group locations with similar risk profiles for setting premiums. Territories are typically defined using the following methods and delineators:

1. ZIP Codes: The most common delineator, as ZIP codes provide a standardized way to segment areas based on localized risk factors like accident rates, crime statistics, and claim frequency. Insurers may use individual ZIP codes or aggregate them into larger territories. [2] [16] [19]

2. Custom Territories: Insurers may create their own territories by combining ZIP codes, counties, cities, or townships into broader zones. These are designed to reflect similar loss experiences, traffic patterns, or demographic characteristics. For example, multiple adjacent ZIP codes with comparable risk may be grouped into one territory. [11] [13] [14]

3. Census Block Groups: For more granular analysis, some insurers use census block groups (small areas with 600-2,000 people) to define territories. These allow for precise risk assessment in densely populated or diverse areas. [16] [19]

4. State-Regulated Territories: Some states impose rules on how territories are defined. For instance, Connecticut uses 18 predefined territories, while California requires territories to be at least 20 square miles and prohibits single-ZIP code territories to ensure fairness and avoid overly specific pricing. [13] [14]

5. Geocoding: Insurers use geocoding tools to map a vehicle’s primary garaging address (where it’s parked most often) to precise coordinates, ensuring accurate assignment to a territory. This helps account for variations within larger geographic units. [18]

Territories are defined based on data like accident frequency, vehicle theft rates, vandalism, weather risks, traffic density, and claims history, which help insurers assess the likelihood and cost of claims in a given area. The boundaries are set to balance statistical homogeneity with practical considerations like regulatory compliance and administrative simplicity.

With nearly 500 food items, 30 carnival rides, and more than 900 free performances, there’s plenty to keep you busy throughout the Minnesota State Fair‘s 12-day run.

It’s a thing here in Minnesota. All walks of life mingle through the entrance gates in Falcon Heights. Check out the one day attendance record.

I showed a house this week in a modest but well-situated neighborhood. It had some problems, but mostly superficial– carpet, paint, appliances, and the like. Yet, even at a price below the comparable sales, it remains on the market. What? Uncertainty.

The property has been through a foreclosure, and as the tax records show, the bank holding the paper, Midfirst Bank, repurchased it. But this is a murky ownership situation.

At a sheriff’s sale, the buyer is not immediately given a full and clear ownership title the way they would in a normal real estate closing. Instead, the buyer typically receives one of two legal instruments depending on the state:

The property is being marketed by the owner who went through foreclosure, even though their right to the property is only through redemption. They would have to find a buyer to settle the full amount owed to Midfirst. This middle-ground ownership area makes the market uneasy. What if the bank wants more than the sheriff’s sale for fees and expenses? What if the property’s condition deteriorates between the offer and closing? Who will handle the repair? Will the title transfer be handled properly in the end?

Minnesota’s foreclosure rate is very low at one-half of one percent of the housing stock. So these sales are rare, and an investor will undoubtedly find it worthwhile to take on as a project. But in areas with insecure property rights and poor banking relations, the surcharge for uncertainty carries a hefty surcharge.

Agnes Callard: ‘Exsanguinating the bodies of people who hold an idea is not a way of getting at the idea itself, and preventing them from being exsanguinated doesn’t preserve the idea. Killing and saving don’t touch ideas: only argument does.’

Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted – Matthew 5:4

From the National Association of Realtor’s Buyer Report:

62% of recent buyers were married couples, 20% were single females, 8% were single males, and 6% were unmarried couples.

I wonder what kind of spread Travis and Taylor will end up with?