This is an excerpt from my working paper, which examines how contemporary economic realities challenge conventional price formation models. Traditional price theory, rooted in neoclassical equilibrium models, struggles to explain modern markets characterized by digital platforms, behavioral anomalies, and network effects. Rather than viewing prices solely as equilibrium outcomes, this section explores price as an information system and coordination mechanism shaped by institutional contexts and evolutionary market processes, proposing alternative approaches that better capture the dynamic nature of pricing in today’s economy.

B. Comparative Analysis: Evaluating Theoretical Frameworks

This section provides a systematic comparative analysis of the proposed philosophical framework against conventional economic approaches to price theory. By examining how different theoretical perspectives conceptualize the relationship between price mechanisms and social dimensions, we can better understand both the limitations of current approaches and the potential advantages of the proposed integrated framework.

Conventional Economic Frameworks: The Separation Paradigm

Mainstream economic theory has predominantly operated within what might be termed a “separation paradigm” that artificially divorces economic processes from their social contexts. This approach has taken several forms, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings but sharing a common tendency to externalize social dimensions from core economic processes.

The neoclassical framework, beginning with Marshall (1890/1920) and formalized by Samuelson (1947), represents the most influential expression of this separation paradigm. This approach treats social costs and benefits as “externalities”—phenomena that exist outside the market mechanism and require correction through policy intervention. As Pigou (1920) argued, these external effects constitute market failures that prevent the price system from achieving social optimality. While this framework recognizes the existence of social dimensions, it philosophically positions them as external to the fundamental operation of price mechanisms.

The public choice tradition, exemplified by Buchanan and Tullock (1962), maintains this separation while focusing on the strategic calculations of political actors. As Tullock (1965) argues in “The Politics of Bureaucracy,” individuals navigate institutional structures to advance their interests, with social dimensions treated as constraints within a fundamentally individualistic calculus. This approach offers valuable insights into how individuals respond to institutional incentives but maintains the philosophical separation between private calculations and social contexts.

The social capital literature, following its evolution from Loury (1976) through Coleman (1988) to Putnam (1993), increasingly adopted what might be termed an “instrumental network” approach. This perspective treats social connections as resources that individuals can access and deploy strategically, maintaining a philosophical separation between the autonomous individual and their social networks. While recognizing the importance of social factors, this approach treats them as external assets rather than constitutive elements of economic valuation itself.

The Integrated Framework: Embeddedness and Unified Valuation

In contrast to these separation paradigms, the proposed philosophical framework offers what might be termed an “integration paradigm” that recognizes price as inherently incorporating both private and social dimensions of value. This comparative analysis highlights several key distinctions:

1. Outcomes vs. Processes

Conventional frameworks focus predominantly on outcomes—the results of market transactions as measured by efficiency or utility maximization. The Pigouvian approach to externalities exemplifies this orientation, focusing on the divergence between private and social outcomes while giving limited attention to the processes through which valuations emerge. Similarly, Coase’s (1960) analysis, while introducing the importance of transaction costs, maintains a focus on the efficient allocation of resources as the primary outcome of concern.

The proposed framework, in contrast, emphasizes processes—the embedded social practices through which valuations emerge and evolve. Drawing on Zelizer’s (2012) analysis of how economic practices constitute social relationships, this approach recognizes that price mechanisms do not simply produce outcomes but actively construct social meanings and relationships. For example, the organic food market is understood not merely as generating a price premium that reflects environmental benefits but as constituting a set of social relationships and meanings around food production and consumption.

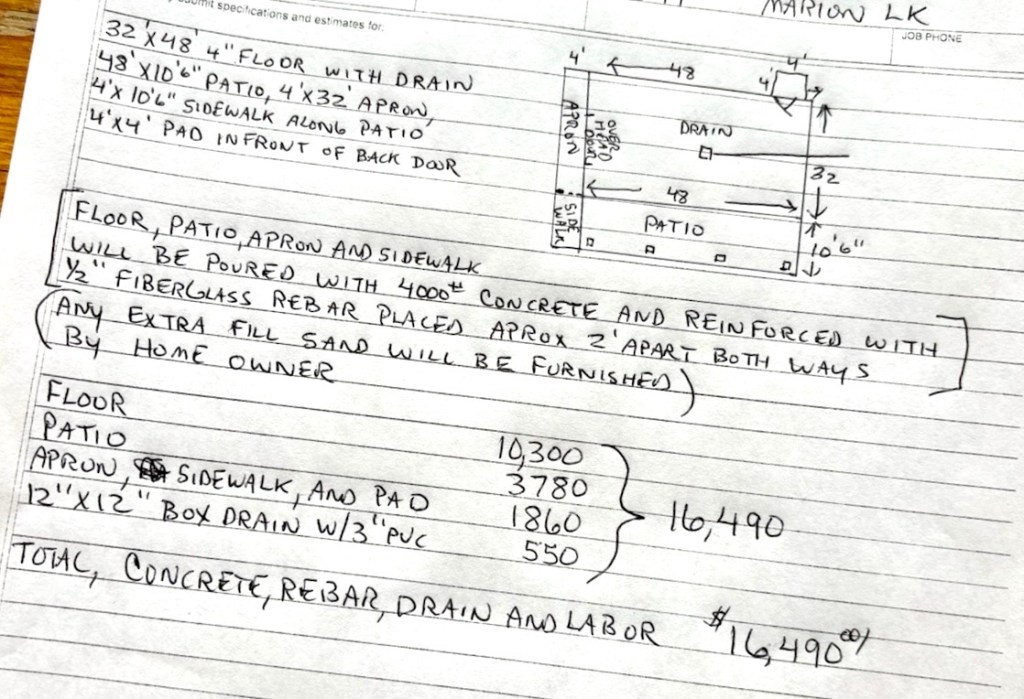

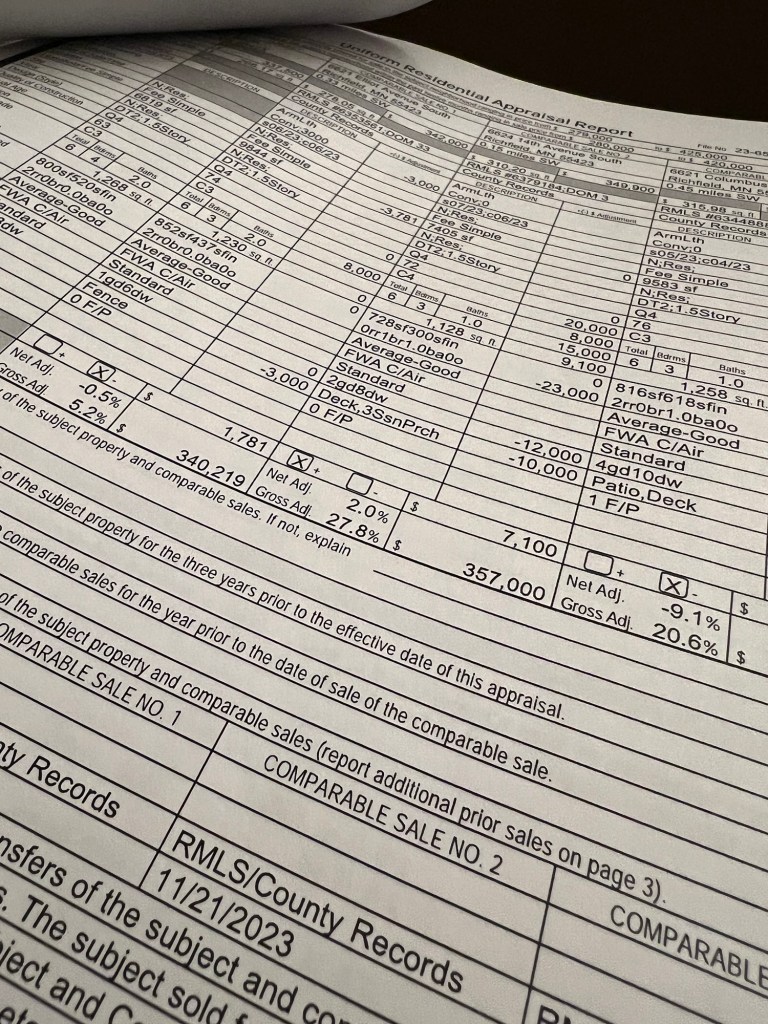

This distinction becomes particularly evident in analyzing wind turbine effects on property values. Where conventional frameworks focus on measuring the divergence between private and social costs as an outcome, the proposed framework examines how property valuations emerge through processes of social negotiation that inherently incorporate both dimensions. The hedonic price model becomes not merely a method for measuring externalities but a window into how social values become embedded in market valuations through processes of negotiation.

2. Calculation vs. Negotiation

Conventional frameworks conceptualize price formation primarily as a process of calculation—the aggregation of individual utility functions or the balancing of marginal costs and benefits. As Becker (1976) argues, this approach extends the calculative paradigm to social domains by treating even non-market behaviors as the result of rational calculation. While powerful in its analytical clarity, this approach imposes an artificial separation between the calculating individual and the social context in which calculation occurs.

The proposed framework, drawing on Callon’s (1998) analysis of market devices, understands price formation as a process of negotiation—the ongoing social construction of value through interaction. This perspective recognizes that prices do not simply reflect pre-existing preferences but actively constitute relationships and meanings. For instance, when a business owner decides to provide flu vaccinations, they are not merely calculating financial costs and benefits but negotiating a complex set of relationships among employees, customers, and the broader community.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often struggle to account for phenomena like voluntary green premiums or corporate social responsibility initiatives. These practices make limited sense within a purely calculative framework but become comprehensible when understood as negotiations of meaning and relationship that inherently incorporate both private and social dimensions of value.

3. Autonomy vs. Interdependence

Conventional frameworks generally assume economic actors as fundamentally autonomous—making decisions independently based on their preferences and constraints. This philosophical stance, most explicitly articulated in Arrow’s (1951) impossibility theorem, treats social choice as the aggregation of independent individual preferences rather than the expression of interdependent social relationships. Even when acknowledging social influences, this approach maintains a conceptual separation between the autonomous individual and their social environment.

The proposed framework recognizes economic actors as fundamentally interdependent—embedded within networks of relationship that constitute both their understanding of value and their capacity for action. Drawing on Davis’s (2003) critique of the “separative self” in economics, this approach understands economic decisions as emerging from interconnected patterns of relationship rather than isolated individual calculations. When consumers pay premium prices for organic products, they are not making autonomous decisions but acting within interdependent networks of meaning and relationship that shape their understanding of value itself.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often treat environmental values or social justice concerns as external to economic valuation—they maintain a philosophical commitment to autonomous individuals whose interdependence is treated as secondary rather than constitutive. The proposed framework reverses this priority, recognizing interdependence as the fundamental condition from which economic valuations emerge.

4. Strategy vs. Meaning

Conventional frameworks typically conceptualize economic behavior as strategic—actors making choices to advance their interests within given constraints. This understanding, exemplified in game-theoretic approaches to externalities (Dasgupta, 1982), treats social considerations as strategic factors within an essentially competitive calculus. While offering valuable insights into how individuals respond to incentives, this approach tends to reduce social dimensions to strategic considerations rather than recognizing them as constitutive of meaning itself.

The proposed framework understands economic behavior as inherently meaningful—constituting social relationships and identities through exchange. Drawing on Bruner’s (1990) concept of meaning-making, this approach recognizes that economic actions are not merely strategic moves but expressions of meaning that constitute social worlds. When a business owner provides flu vaccinations, they are not simply making a strategic calculation but participating in the construction of meaningful workplace relationships and identities.

This distinction helps explain why conventional approaches often struggle to account for the emotional and symbolic dimensions of economic behavior—they maintain a philosophical commitment to strategic rationality that marginalizes considerations of meaning. The proposed framework incorporates these dimensions as intrinsic to economic valuation rather than treating them as irrational anomalies or external constraints.

Comparative Empirical Implications

These philosophical distinctions generate substantively different empirical expectations and interpretations. Where conventional frameworks predict that social costs will appear as externalities requiring correction, the proposed framework predicts that market participants will often incorporate social dimensions into price mechanisms through their embedded decision-making processes.

The hedonic pricing model provides a useful comparative lens. Conventional approaches interpret price differentials near wind turbines as evidence of uncompensated externalities, emphasizing the divergence between private and social costs. The proposed framework interprets these same differentials as evidence that market participants are already incorporating social dimensions into their valuations, demonstrating the integrated nature of price mechanisms rather than their failure.

Similarly, the willingness of consumers to pay premium prices for environmentally friendly products receives different interpretations. Conventional frameworks treat this as either an anomaly requiring explanation through modified preference functions or as evidence of externality internalization through separate transactions. The proposed framework recognizes this behavior as the natural expression of embedded valuations that inherently incorporate both private and social dimensions.

Integration with Existing Economic Insights

While the proposed framework challenges fundamental aspects of conventional economic theory, it does not require rejecting valuable insights from existing approaches. Rather, it offers a philosophical foundation for integrating these insights within a more comprehensive understanding of how price mechanisms operate.

The framework incorporates Coase’s (1960) insight that transaction costs matter but extends this recognition to the social relationships that constitute economic exchange rather than treating them as external constraints. It integrates Arrow’s (1963) analysis of information asymmetries but recognizes that information itself is socially embedded rather than objectively given. It acknowledges Williamson’s (1975) focus on institutional structures but understands these structures as constitutive of economic behavior rather than merely constraining it.

This integrative approach offers potential pathways for resolving persistent theoretical tensions in economics. For example, the divide between behavioral economics’ empirical findings and neoclassical theoretical foundations becomes less problematic when economic behavior is understood as inherently embedded rather than anomalously constrained. Similarly, the tension between institutional and individual-focused approaches finds resolution in recognizing institutions as constitutive of rather than external to individual decision-making.

Comparative Philosophical Robustness

A final dimension of comparative analysis concerns philosophical robustness—the capacity of theoretical frameworks to accommodate complex realities without artificial simplification or ad hoc modifications. Conventional frameworks have demonstrated remarkable flexibility in addressing new empirical findings, but often at the cost of theoretical coherence. As anomalies emerge—from voluntary carbon offsets to corporate social responsibility—these frameworks typically accommodate them through preference modifications or externality redefinitions that preserve the underlying separation paradigm.

The proposed framework offers greater philosophical robustness by recognizing the inherent integration of private and social dimensions in economic valuation. Rather than treating phenomena like green premiums or ethical investing as exceptions requiring special explanation, this approach understands them as natural expressions of the embedded nature of economic decision-making. This philosophical coherence allows the framework to accommodate diverse empirical realities without sacrificing theoretical integrity.

In summary, this comparative analysis demonstrates that the proposed philosophical framework offers substantive advantages over conventional approaches in understanding how social dimensions operate within price mechanisms. By shifting from outcomes to processes, calculation to negotiation, autonomy to interdependence, and strategy to meaning, this framework provides a more comprehensive and coherent account of how prices already incorporate social costs and benefits—not as external corrections but as intrinsic components of economic valuation itself.