Two recent articles by prominent housing policy voices reveal a shared concern about the structural limitations of the YIMBY movement’s traditional approach. Both Chris Elmendorf’s “YIMBYism started as a single-issue movement. It’s time to think bigger” and Matthew Yglesias’s “The power of a single-issue group” examine how YIMBY organizations have operated as focused advocates for increased housing density, but each author suggests that this narrow framework may need evolution to achieve lasting success.

The Competitive Model of Single-Issue Advocacy

Both authors describe YIMBY groups through a similar structural lens: as collections of people united around the singular goal of increasing housing density through land use reform and community lobbying. This approach has positioned YIMBY organizations as competitors in the arena of local politics, where they must vie against other community interests—from neighborhood character preservation to parking concerns—to secure favorable outcomes.

This competitive dynamic has been YIMBY’s strength. As Elmendorf notes, “The signal advantage of one-issue groups is that they can work with almost any legislator. By not taking stances on peripheral issues, they avoid making enemies.” Similarly, Yglesias emphasizes that “the strength of YIMBYism over the past 10-15 years has largely derived from its single-issue orientation during a time of relentless political polarization.” The movement has achieved bipartisan success across diverse political landscapes precisely because it hasn’t alienated potential allies by taking controversial positions on unrelated issues.

However, both authors identify a fundamental limitation in this competitive approach. When YIMBY groups operate as single-issue advocates, they inherently position themselves in opposition to other legitimate community concerns rather than as partners in comprehensive neighborhood improvement.

The Case for Pluralistic Collaboration

The articles converge on a crucial insight: sustainable support for housing density may require YIMBY groups to embrace a more pluralistic approach that considers multiple public goods simultaneously. Rather than competing against other neighborhood priorities, they could collaborate to address the full spectrum of urban challenges.

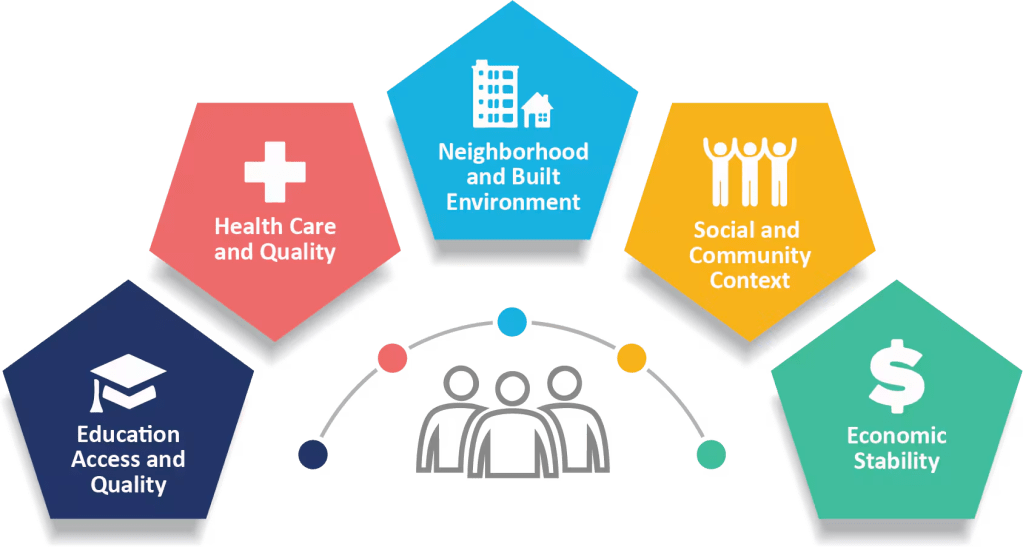

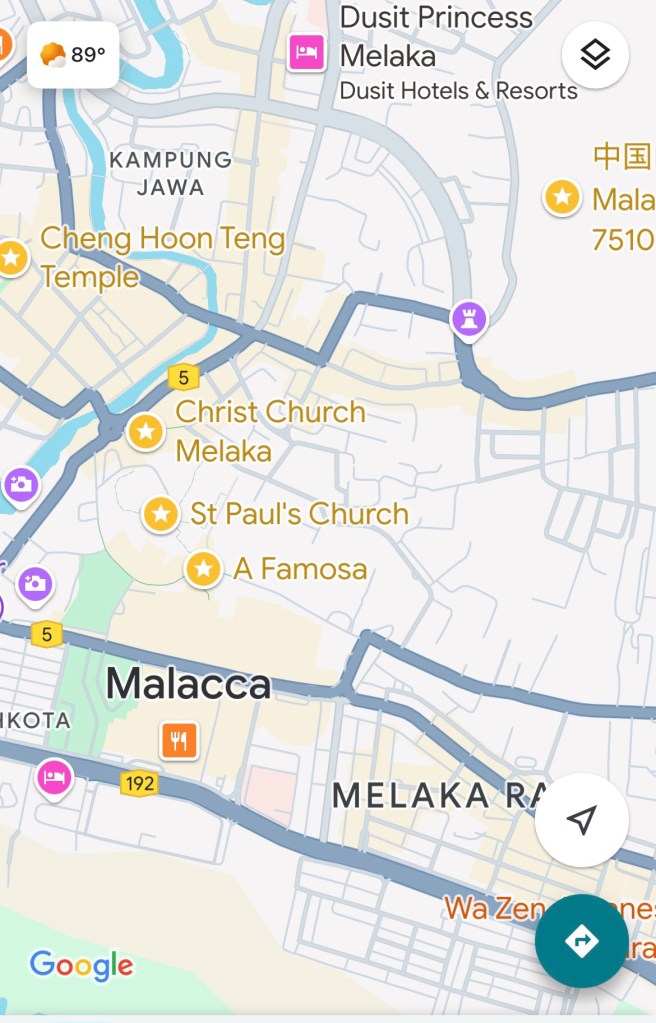

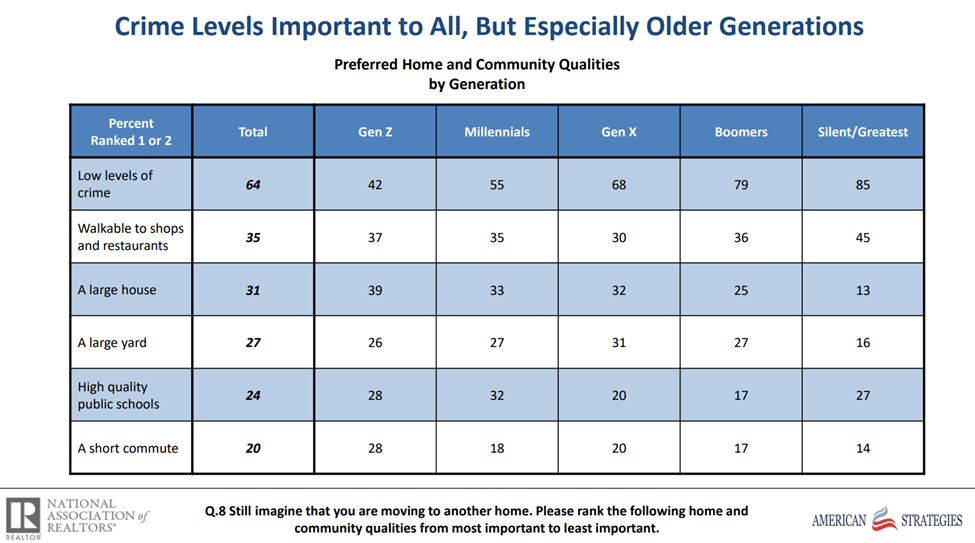

Elmendorf argues that this shift is not just strategically wise but empirically necessary. His research reveals that “people who feel good about big cities want existing cities to become more canonically city-like.” This finding suggests that support for density depends heavily on broader urban quality of life—including schools, transportation, public safety, and cultural amenities.

Yglesias acknowledges the value of this broader approach while defending the continued importance of single-issue organizing. He recognizes that multi-issue coalitions can offer something valuable to skeptical neighbors: addressing their concerns about construction impacts by simultaneously improving schools, transit, and safety.

Beyond Zero-Sum Thinking

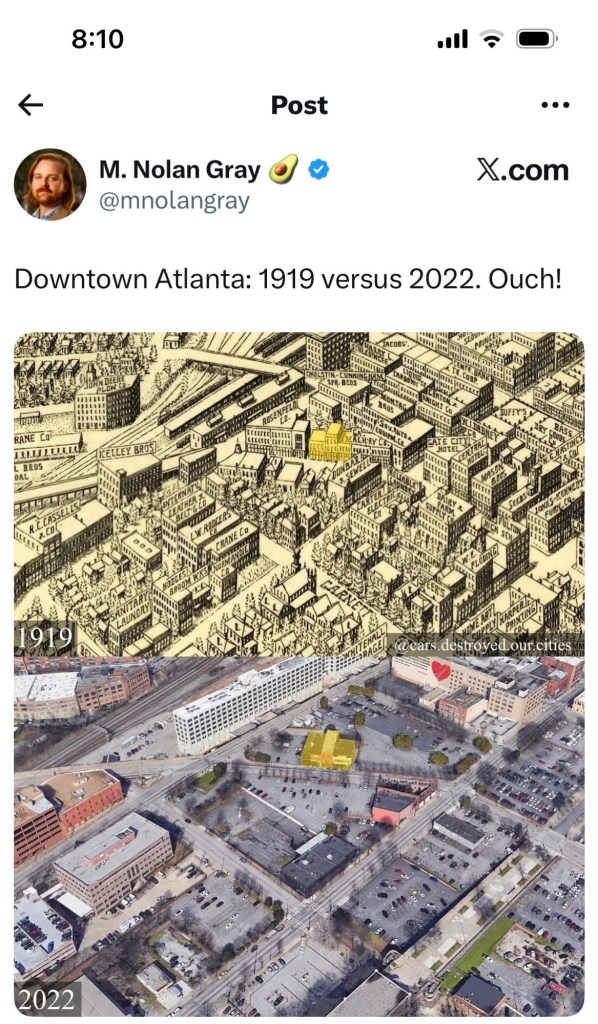

The structural shift both authors envision moves beyond zero-sum competition toward collaborative problem-solving. Instead of viewing neighborhood concerns as obstacles to overcome, a more pluralistic YIMBY approach would treat them as legitimate issues requiring integrated solutions.

This doesn’t mean abandoning the core mission of increasing housing supply, but rather embedding that mission within a broader framework of neighborhood improvement. As Elmendorf suggests, such an approach could offer community members a compelling trade-off: “You may not like all the buildings, but you’ll love the great schools, safe streets, fast transit, and thriving business that we’ll deliver.”

The Challenge of Multiple Public Goods

Both authors acknowledge the complexity of this transition. Weighing multiple public goods requires sophisticated political judgment and potentially controversial prioritization decisions. A group focused solely on housing can avoid taking positions on education funding or transit investment; a multi-issue coalition cannot.

Yet this complexity may be precisely what sustainable urban policy requires. Rather than treating housing, transportation, education, and public safety as separate domains competing for attention and resources, effective urban governance demands understanding their interconnections and potential synergies.

Conclusion

While Elmendorf and Yglesias differ on whether YIMBY organizations should fully embrace multi-issue coalition building or maintain some single-issue focus, they share a recognition that the movement’s competitive, narrow approach has structural limitations. The path forward likely involves both preserving the strategic advantages of focused advocacy while developing new organizational forms capable of the pluralistic collaboration that sustainable urban development requires.

The evolution from single-issue competition to multi-issue partnership represents more than a tactical shift—it reflects a deeper understanding that creating livable, dense communities requires addressing the full spectrum of residents’ concerns rather than simply winning narrow victories on housing policy alone.