Paul Erdos, featured yesterday, chose a lifestyle that led to a striking number of shared work projects. Due to the sheer number of work friends, a number system was developed to keep track of the network that worked on shared ideas. Chat explains.

Paul Erdős, one of the most prolific mathematicians of the 20th century, collaborated with an extraordinary number of researchers throughout his life. His collaborators are often counted as part of the famous “Erdős Number” system, where Erdős himself has an Erdős Number of 0, his direct collaborators have a number of 1, their collaborators have a number of 2, and so on.

Estimated Number of Collaborators

Erdős collaborated with approximately 511 mathematicians on research papers during his lifetime. These collaborations resulted in over 1,500 papers, making him one of the most prolific authors in mathematical history.

This number of collaborators reflects Erdős’s unique approach to mathematics—he would travel extensively, visiting mathematicians worldwide, and work intensively with them on specific problems. This collaborative approach led to his reputation as a “mathematical nomad.”

Now, how do you think that work went when you think about all these math types puzzling over combinatorics or vertices of convex polygons? Did Erdos have a payroll and dole out cash? It seems it was the opposite. Collaborators and friends brought him into their home and put him up so he could work with them out of their university. This is not work compensated through pecuniary means.

So what’s in it for the collaborators? The Edos number, of course. Being in the Erdos network gives one sense of participation in the mathematical theory underway, and then their Erdos number specifies a claim to a distance from Erdos himself.

To recap, this type of work is voluntary and participatory, and the end product feeds into a jointly held asset—a school of thought in mathematics. Money is not the primary motivation for action. Membership in the network and the potential for the elevated position are the compensating factors. Every participant has access to the knowledge. It is a public good.

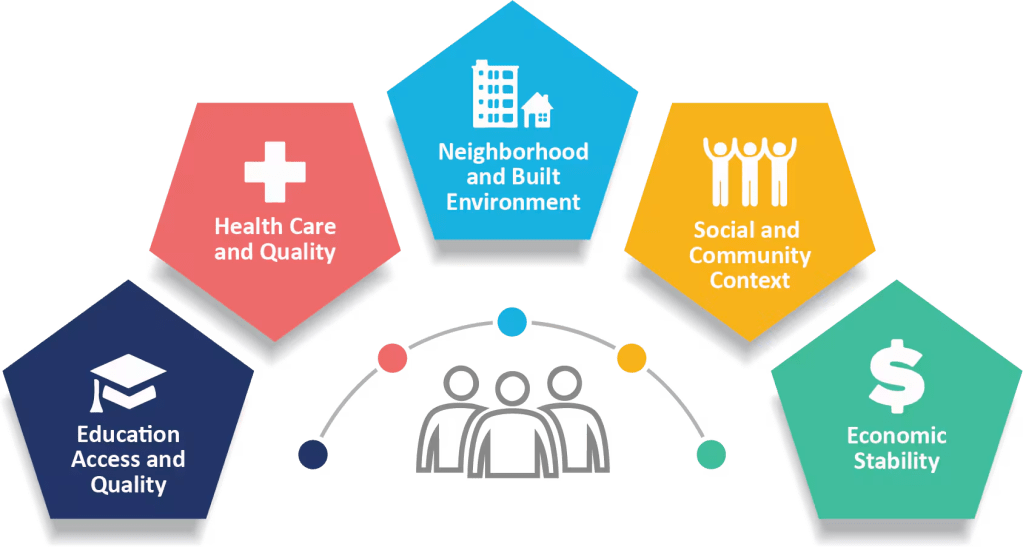

Here’s Chat’s visual.

Is it a public good to the whole world? In a sense, yes, but not in a practical sense. Just like it’s not practical to say the streets of Fargo, ND, are public to the whole world. The knowledge is open, but only a few will have the talents and learned knowledge to comprehend it. Only people in the geographic vicinity of Fargo will use their streets.

Is there externalizing and internalizing going on? Sure- when a new entrant learns a theorem, it becomes part of their knowledge. They have acquired the benefit, internalized, of the learned network. If a few of them collaborate on a textbook and sell it for their private pecuniary gain, they externalize knowledge and realize a gain. These actions do not conflict or reduce the network’s accomplishment. They add to the power and benefit of the group. The image you see inflates.

Paul Erdos’ life had living constraints, just as ours do. Yet the value of his research was such that he could be entertained at associates’ homes to assist in writing all 1,500 papers he left to the world.