This is an excerpt from my working paper which examines how contemporary economic realities challenge conventional price formation models. Traditional price theory, rooted in neoclassical equilibrium models, struggles to explain modern markets characterized by digital platforms, behavioral anomalies, and network effects. Rather than viewing prices solely as equilibrium outcomes, this section explores price as an information system and coordination mechanism shaped by institutional contexts and evolutionary market processes, proposing alternative approaches that better capture the dynamic nature of pricing in today’s economy.

I think this section needs some more work. But here’s what we have so far:

II. Literature Review

A. Mainstream Economic Philosophy Foundations

The philosophical foundations of mainstream economic theory have been constructed upon a series of conceptual separations that artificially divide the economic from the social, the private from the public, and the individual from the collective. This review traces these separations through key philosophical traditions in economic thought, examining how they have shaped our understanding of price mechanisms and market functioning.

The Neoclassical Framework and Methodological Individualism

The neoclassical paradigm, beginning with Marshall (1890/1920) and formalized by Samuelson (1947), established methodological individualism as the dominant analytical approach to economic phenomena. This philosophical stance treats social aggregates as reducible to the actions of autonomous utility-maximizing individuals whose preferences are taken as given. As Arrow (1994, p. 1) acknowledges, “It is a touchstone of accepted economics that all explanations must run in terms of the actions and reactions of individuals.”

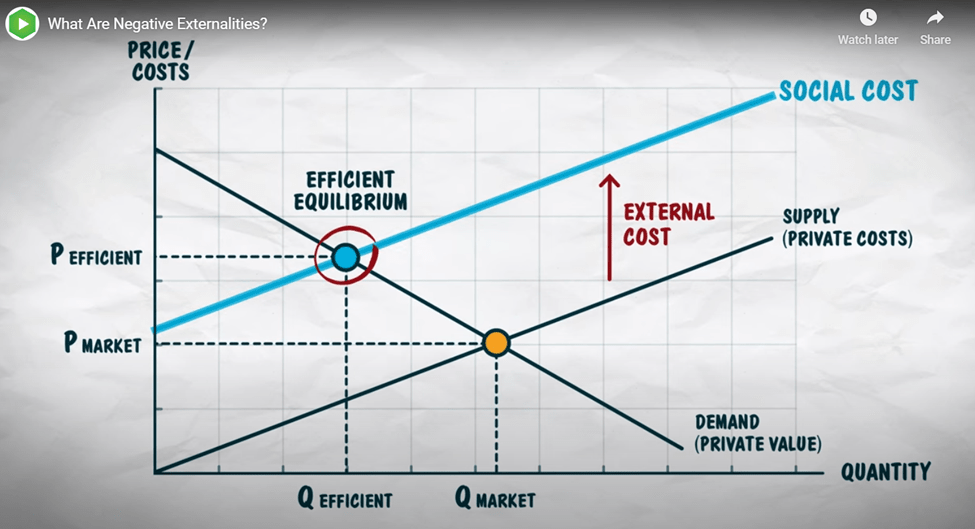

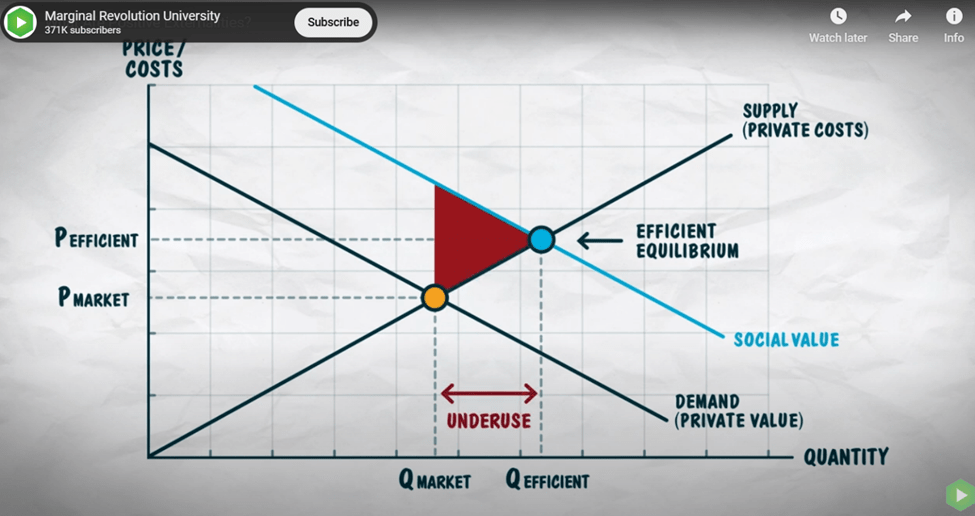

This methodological commitment has profound implications for price theory. Within the neoclassical framework, prices emerge from the aggregation of individual utility functions, with social dimensions treated as externalities—phenomena that exist outside the core market mechanism. Pigou’s (1920) seminal work on welfare economics formalized this separation, positioning social costs as divergences between private and social valuations that require correction through policy interventions. This philosophical framing fundamentally shapes how economists conceptualize market processes, treating the social as external to rather than constitutive of economic valuation.

Interestingly, even as neoclassical economics rigorously applies methodological individualism, it implicitly relies on group concepts without adequately defining them. Markets, firms, industries—these collective entities serve as the backdrop for individual decisions, yet their constitutive nature remains undertheorized. It is as if economic theory performs an elaborate mimetic gesture, tracing the outlines of social structures while focusing exclusively on the individuals within them, like a mime whose white-gloved hands demarcate invisible boundaries that audiences must imagine rather than observe directly.

Public Choice Theory and Rational Actor Models

The public choice tradition, exemplified by Buchanan and Tullock (1962), extends methodological individualism into the realm of political decision-making. By applying rational actor models to public policy, this approach treats political processes as aggregations of individual utility calculations rather than expressions of collective values. As Buchanan (1984, p. 13) argues, “There is no organic entity called ‘society’ that exists independently of the individuals who compose it.”

This philosophical stance reinforces the separation between economic and social dimensions by treating political processes themselves as markets—mechanisms for aggregating individual preferences rather than constructing collective meanings. While providing valuable insights into institutional incentives, this approach systematically marginalizes the embedded nature of economic decision-making within social contexts.

Again, the public choice tradition alludes to groups—voters, interest groups, bureaucracies—while consistently reducing them to collections of utility-maximizing individuals. The collective dimensions that give these groups meaning and coherence are acknowledged as backdrop but rarely examined as constitutive elements of the analysis itself. The mime continues to trace invisible boundaries without substantiating the spaces they enclose.

Transaction Cost Economics and Institutional Analysis

Williamson’s (1975, 1985) transaction cost economics represents a significant extension of economic analysis into institutional structures, examining how organizations emerge to reduce the costs of market exchange. While acknowledging that economic activities occur within institutional contexts, this approach maintains the philosophical separation between economic and social dimensions by treating institutions primarily as efficiency-enhancing mechanisms rather than socially embedded practices.

As Williamson (1985, p. 18) argues, “Transaction cost economics attempts to explain how trading partners choose, from the set of feasible institutional alternatives, the arrangement that protects their relationship-specific investments at the least cost.” This framing maintains the priority of efficiency considerations while treating social dimensions as constraints rather than constitutive elements of economic organization.

Despite its focus on organizations and institutions, transaction cost economics continues to treat these collective entities as instrumental arrangements serving individual interests rather than examining how they constitute economic actors themselves. The group remains an instrumental backdrop—a cost-minimizing solution to coordination problems—rather than a constitutive dimension of economic reality. The mime’s gestures outline organizational boundaries without examining how these boundaries shape the identities and preferences of those within them.

Behavioral Economics and the Modified Individual

Behavioral economics, pioneered by Kahneman and Tversky (1979) and expanded by Thaler (1991) and others, challenges the rational actor model by identifying systematic deviations from utility maximization. While this approach introduces psychological complexity into economic analysis, it maintains the philosophical separation between economic and social dimensions by treating these deviations as cognitive biases rather than expressions of social embeddedness.

As Thaler and Sunstein (2008, p. 6) argue in their influential work on nudge theory, “The false assumption is that almost all people, almost all of the time, make choices that are in their best interest or at the very least are better than the choices that would be made by someone else.” This framing maintains the philosophical commitment to individual choice while acknowledging limitations in cognitive processing, without fundamentally challenging the separation between economic and social dimensions.

Here too, the social dimension appears as an influence on individual decision-making rather than a constitutive element of economic action. Groups function as reference points that bias individual judgments rather than fields of practice that constitute economic meaning. The mime continues to gesture at social influences without substantiating the collaborative production of economic reality that these influences represent.

B. Critical Theoretical Intersections

Against these mainstream approaches, several critical traditions have challenged the separation between economic and social dimensions, offering theoretical resources for reconceptualizing price mechanisms as inherently incorporating both private and social valuations.

Social Capital Theory: From Group Phenomenon to Individual Asset

Loury’s (1976) groundbreaking paper, “A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences,” introduced social capital as a group-contained phenomenon that shaped economic opportunities. This original conception recognized the embedded nature of economic action within social contexts, particularly in explaining persistent racial disparities. As Loury (1976, p. 176) argued, “The social context within which individual maturation occurs strongly conditions what otherwise equally capable individuals can achieve.”

However, as the concept evolved through Coleman (1988), Putnam (1993), and Lin (2001), it increasingly shifted toward what might be termed an “instrumental network” approach—treating social capital as a resource that individuals could access and deploy strategically rather than a field of relationships in which they were embedded. Coleman (1988, p. S98) exemplifies this shift in defining social capital as “a variety of entities with two elements in common: They all consist of some aspect of social structures, and they facilitate certain actions of actors—whether persons or corporate actors—within the structure.”

This conceptual migration represents a critical juncture in economic philosophy, where a potentially transformative concept that recognized the inherent embeddedness of economic action was gradually reframed to fit within methodological individualism. The group-level phenomenon that Loury identified became increasingly individualized—a network resource rather than a constitutive field of practice.

Notably, throughout this evolution, the central concept of “the group” remains persistently undefined. Social capital theorists allude to communities, networks, and associations without developing a rigorous philosophical account of what constitutes a group beyond the aggregation of connected individuals. The mime traces ever more elaborate networks of connection without substantiating what makes these networks constitutive rather than merely instrumental.

Embeddedness and Economic Sociology

Granovetter’s (1985) influential paper, “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness,” directly challenged the separation between economic and social dimensions by arguing that economic actions are “embedded in concrete, ongoing systems of social relations.” This perspective reframed economic behavior as inherently social rather than merely influenced by social factors.

As Granovetter (1985, p. 487) argues, “Actors do not behave or decide as atoms outside a social context, nor do they adhere slavishly to a script written for them by the particular intersection of social categories that they happen to occupy.” This recognition that economic action is constitutively social rather than merely constrained by social factors represents a fundamental philosophical challenge to the separation paradigm.

Similarly, Zelizer’s (2012) work on “relational work” examines how economic transactions constitute social relationships rather than merely reflecting them. As she argues, “Economic transactions connect persons and establish meaning-laden relationships.” This perspective challenges the philosophical separation between economic and social dimensions by recognizing their mutual constitution.

Yet even within economic sociology, there remains a tendency to allude to social structures without developing a rich philosophical account of their ontological status. The mime gestures toward “concrete, ongoing systems of social relations” without fully substantiating how these systems exist beyond the interactions of individuals within them.

Ecological Economics and Systems Thinking

Ecological economics, developed by Georgescu-Roegen (1971), Daly (1977), and others, challenges the separation between economic and ecological systems by positioning the economy as a subsystem of broader biophysical processes. This approach recognizes the inherent embeddedness of economic activities within ecological contexts, challenging the artificial boundaries that conventional economics draws around market processes.

As Daly (1990, p. 1) argues, “The economy is a subsystem of the finite biosphere that supports it.” This simple yet profound observation challenges the philosophical foundations of mainstream economics by recognizing that economic activities are intrinsically rather than accidentally connected to their ecological contexts.

More recently, Raworth’s (2017) “doughnut economics” has extended this systems thinking approach, arguing for a reconceptualization of economic theory that recognizes social and ecological dimensions as constitutive boundaries of economic activity rather than external constraints. As she argues, economic theory must be “embedded in society and in nature, and that’s inherently connective.”

However, even these systemic approaches often maintain a distinction between “the economy” and its social and ecological contexts, preserving a conceptual separation even while arguing for integration. The mime traces the connections between systems while maintaining their distinct identities, without fully examining how these identities themselves are mutually constituted.

Feminist Economics and the Critique of Separative Self

Feminist economic philosophy has provided some of the most profound challenges to the separation paradigm through its critique of the “separative self” that underpins mainstream economic theory. Nelson (2006), Folbre (1994), and others have questioned the philosophical assumptions about autonomy and independence that shape conventional economic analysis.

As Nelson (2006, p. 30) argues, “The image of economic man as self-interested, autonomous, and rational creates a distorted view of economic life. Most economic decisions and actions are undertaken by people who are deeply connected to others.” This critique challenges not merely the assumptions of rational choice theory but the deeper philosophical conception of the economic actor as fundamentally separate from social contexts.

Folbre’s (1994) work on care economics further demonstrates how economic decisions inherently incorporate social dimensions, particularly in domains traditionally excluded from economic analysis. As she argues, “The invisible hand is all thumbs when it comes to care.” This observation highlights how conventional economic frameworks systematically marginalize activities where social dimensions are most evident.

Yet even these critical perspectives often maintain a focus on individuals—albeit connected and caring ones—without fully developing an alternative ontology of the social. The mime gestures toward connection and care without fully substantiating the collective dimensions these concepts imply.

C. Syntheses and Gaps in Current Literature

The literature reveals both promising directions for reconceptualizing the relationship between economic and social dimensions and persistent gaps that the current research aims to address.

Toward an Integrated Understanding

Several theoretical developments suggest potential pathways toward a more integrated understanding of price mechanisms. Lawson’s (2007) critical realist approach challenges the ontological assumptions of mainstream economics, arguing for a recognition of economic phenomena as emerging from “structured interrelationships in practices and positions.” This philosophical stance aligns with the current research’s emphasis on the inherently social nature of price mechanisms.

Similarly, Hodgson’s (2019) recent work on institutional economics provides theoretical resources for understanding how social institutions constitute economic behaviors rather than merely constraining them. As he argues, “Institutions not only constrain options, they establish the very criteria by which people discover their preferences.” This insight suggests how social dimensions might be understood as intrinsic to rather than separate from price mechanisms.

The Missing Ontology of the Group

Despite these promising directions, a significant gap remains in the philosophical understanding of how social dimensions operate within price mechanisms. Across divergent theoretical traditions—from neoclassical economics to critical alternatives—there persists a tendency to allude to groups without developing a rich philosophical account of their ontological status.

This mimetic quality of economic theory—gesturing toward social structures while focusing primarily on individuals within them—represents a critical limitation in current approaches. Like a mime whose white-gloved hands trace invisible boundaries, economic theory repeatedly outlines social dimensions without substantiating them philosophically. Markets, firms, communities, networks—these collective entities appear throughout economic literature without rigorous examination of their constitutive nature.

The present research aims to address this gap by developing a philosophical framework that recognizes price mechanisms as inherently social institutions rather than merely technical devices. By reconnecting with Loury’s original insight that social capital represents a group-contained phenomenon, this research seeks to recover and extend a more integrated understanding of how social dimensions operate not around but within price mechanisms themselves.

As the subsequent sections will demonstrate, this reconceptualization has profound implications for how we understand market processes, offering a more coherent theoretical account and opening new possibilities for addressing complex socioeconomic challenges through a more sophisticated understanding of how prices already incorporate both private and social dimensions of value.