What is Capital Theory in Economics?

Capital theory is the branch of economics that studies the nature, role, measurement, and productivity of capital — the produced means of production (machines, factories, tools, infrastructure, software, etc.) that are used to produce goods and services.

It tries to answer fundamental questions like:

- What exactly is “capital”?

- How should it be measured?

- How does capital contribute to economic growth and income distribution (wages vs. profit/interest)?

- Why does the return on capital (interest rate or profit rate) behave the way it does?

Capital theory has been one of the most controversial and technically difficult areas in economics, especially in the 20th century.

Key Concepts and Debates

- Capital as a homogeneous “fund” (neoclassical view)

- Mainstream neoclassical economics (since the late 19th century) treats capital as a single, measurable quantity (like “dollars of capital” or a “stock of value”).

- In simple production functions (e.g., Y = F(K, L)), K (capital) is treated like labor L — you can smoothly substitute one for the other.

- The interest rate is the price that equilibrates saving and investment.

- The Cambridge Capital Controversy (1950s–1970s) – the big critique

- Economists from Cambridge, UK (Joan Robinson, Piero Sraffa, Luigi Pasinetti) challenged the neoclassical view.

- Major problems they exposed:

- Reswitching: The same technique of production can become profitable again at lower (or higher) interest rates, destroying the simple idea that lower interest rates always lead to more “capital-intensive” techniques.

- Capital reversing: Higher interest rates can sometimes lead to using more capital-intensive methods — the opposite of what neoclassical theory predicts.

- Measurement problem: You cannot measure the “quantity of capital” independently of the interest rate or profit rate, because capital goods are heterogeneous (a robot ≠ a shovel). Their value depends on future profits, which depend on the interest rate — a circularity.

- Conclusion of the critics: The aggregate production function and the idea of a downward-sloping demand curve for capital are logically flawed.

- Austrian view (Böhm-Bawerk, Hayek, Lachmann)

- Capital is highly heterogeneous and time-structured.

- Production takes time; capital goods are “intermediate goods” at different stages of completion.

- Emphasizes the “period of production” or “roundaboutness”: more productive methods are more time-consuming.

- Interest originates from time preference (people value present goods over future goods).

- Post-Keynesian / Sraffian view

- Rejects marginal productivity theory of distribution.

- The rate of profit is determined by monetary factors, class struggle, or growth requirements, not by the “marginal product of capital.”

- Capital is valued in terms of its own reproduction cost (Sraffa’s “price of production”).

- Modern mainstream response

- After the Cambridge controversy, most neoclassical economists largely ignored the deep logical problems and continued using aggregate production functions for practical reasons (they work reasonably well empirically in many contexts).

- Some (e.g., “new growth theory”) shifted focus to knowledge, human capital, and ideas rather than physical capital.

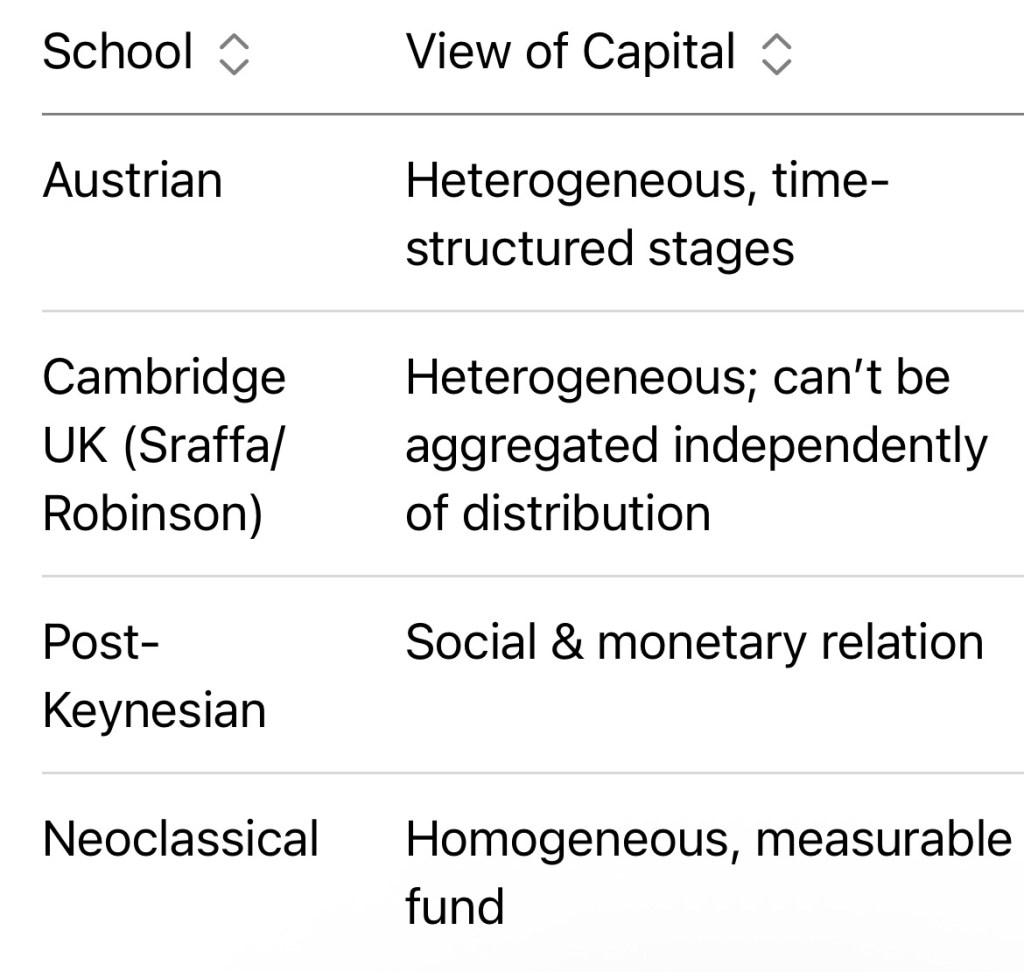

Summary Table of Major Schools

Bottom Line

Capital theory is the attempt to understand one of the most important concepts in economics — capital — and it remains unresolved. The mainstream treats capital as a simple scalar quantity for modeling convenience, but the Cambridge controversies showed that this simplification has serious logical flaws once you dig into the details. The debate is largely dormant in mainstream teaching but still very much alive among economic methodologists and heterodox economists.